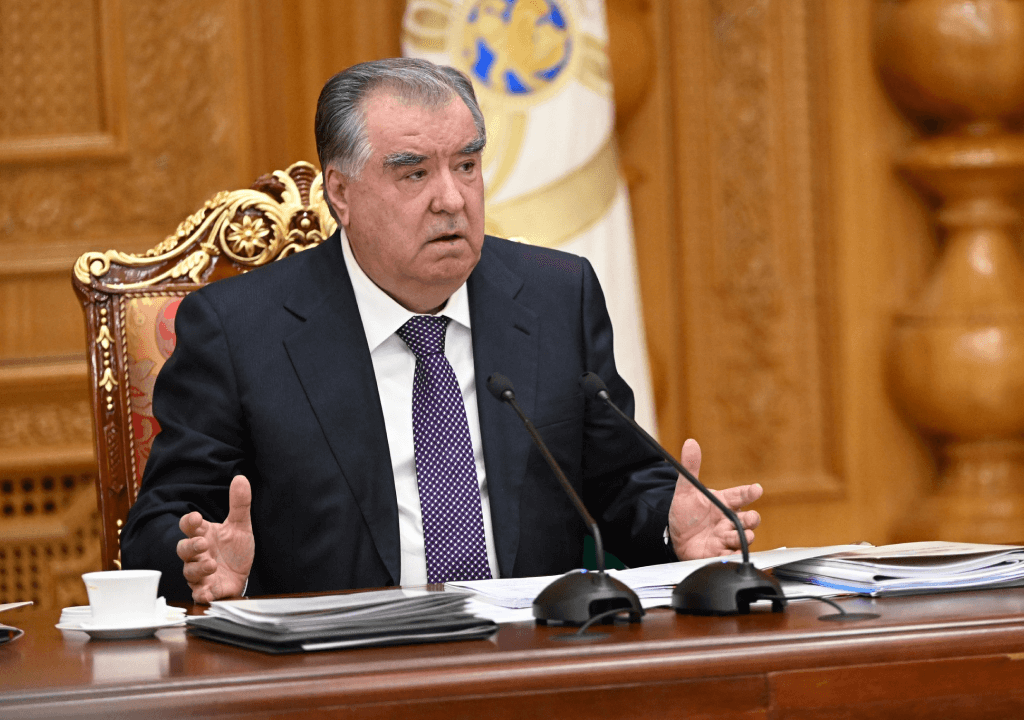

Tajikistan, long regarded as a prime example of a sham democracy, is setting the stage for a coronation. President Emomali Rahmon, in power since 1992 and undisputed leader since 1998, is systematically preparing his son, Rustam Emomali, to take over the presidency. This unfolding succession bears all the hallmarks of a dynastic transfer of power, proceeding alongside a persistent campaign to suppress opposition and centralize authority.

Weeks after the parliamentary elections—where the ruling party secured yet another overwhelming victory, widely condemned by international observers and local critics as neither free nor fair—Rahmon began a wave of high-level government reshuffles, replacing experienced officials with loyalists. Political analysts interpret these moves not as reforms, but as strategic consolidations, clearing a direct path for Rustam’s seamless ascension.

Rahmon Accelerates Power Transfer

Since the beginning of 2025, Rahmon has reshaped Tajikistan’s state security apparatus, with the Ministry of Internal Affairs being the latest to undergo a personnel overhaul. In an April 22 presidential statement, Rahmon announced sweeping changes at both the national and district levels, stressing the importance of improving the training of young personnel within the Interior Ministry.

As Rahmon removes veteran leaders from key ministries, he simultaneously elevates his 37-year-old son, Rustam, to more influential positions. Already the mayor of Dushanbe and the speaker of the senate, Rustam is increasingly taking on prominent roles. In an unprecedented break from protocol, Rahmon had Rustam deliver the annual New Year’s address to the nation—the first time since 1994 that Rahmon himself did not deliver the speech.

Rahmon has also shuffled key personnel to oust powerful figures who may not support the dynastic succession, removing potential opposition to Rustam’s authority.

Challenges still await Rustam

Foreign observers remain skeptical that Rustam Emomali can sustain himself at the helm of Tajik politics, despite the calculated maneuvering by his father, President Emomali Rahmon. Two formidable obstacles threaten the smooth execution of the dynastic handover. First, opposition appears to be brewing within Rahmon’s own extended family, with some influential members reportedly doubting Rustam’s ability to safeguard the political and financial interests of the ruling clan. Second, the country’s persistent economic malaise—defined by widespread poverty and chronic unemployment—offers little structural support for a stable transition of power.

In March, during Rahmon’s visit to Moscow, Russia’s Nezavisimaya Gazeta noted that the succession question in Tajikistan has been discussed for more than five years. Yet, despite years of speculation, the paper argued that the political and socio-economic preconditions for a hereditary transfer of power remain absent.

During that same trip, Rahmon reportedly sought Moscow’s endorsement for a Tajik political dynasty. According to the Nezavisimaya analysis, any Russian support would likely come with a price—most notably, access to investment opportunities in Tajikistan’s renewable energy sector and rare earth mineral reserves.

Some analysts believe that Rahmon’s recent personnel purges may have backfired, weakening rather than bolstering Rustam’s standing. They warn that the wholesale removal of senior officials could spark internal power struggles, not stability. The prolonged ambiguity surrounding the transition has begun to erode the patience of even Rahmon’s most loyal supporters. Observers also stress that internal divisions within the regime are deepening, and that Rustam lacks the authority and command his father has long wielded to keep the country in check.

Democracy – A Distant Dream?

Dynastic politics in Tajikistan now appear nearly inevitable. The country’s hollow elections and a weak, ineffective opposition lack both the resolve and the ability to change this trajectory. With the scars of civil war still visible and increasing concerns over Islamist radicalization and foreign interference, the regime has successfully rallied the public around nationalism, framing continued leadership under the current regime as the only safe option.

The banned Islamic Renaissance Party of Tajikistan (IRPT), once the country’s leading opposition force, has joined three plaintiffs in filing a case with the International Criminal Court, accusing President Emomali Rahmon’s administration of crimes against humanity. However, the impact of this legal challenge seems limited. International justice moves at a glacial pace, and Rahmon enjoys the protection of Moscow’s unwavering support.

Yet the future remains uncertain. If widespread discontent eventually leads to unrest, Islamist factions may seize the opportunity to fill the void. If Rustam Emomali fails to secure power, Russia could intervene and install a more reliable alternative. So, For now, true democracy in Tajikistan remains an elusive dream.