South Korea is going through one of its most turbulent political crises in recent history. Long-standing political tensions boiled over when Yoon Suk-yeol, then president, declared a national emergency and attempted to seize control of parliament, prompting lawmakers and protesters to storm the building. After several attempts, lawmakers impeached Yoon and put him on trial, where he now faces the possibility of the death penalty.

These dramatic events deeply divided the country—both politically and socially—and pushed it to a toxic level. Amid the crisis, the acting vice president announced a new presidential election. Although many feared the vote would deepen divisions and chaos, it has helped the nation refocus on its most urgent challenges.

An Election to Save South Korea

South Korea will elect its 14th president on June 3rd, a vote moved up from 2027 due to a constitutional requirement to fill the vacant presidency within 60 days. The election comes amid a tense political climate, but it has also sparked renewed focus on the everyday concerns of citizens—issues that were long neglected during months of political infighting.

Once hailed as one of Asia’s great economic success stories, South Korea now faces a range of deep-rooted challenges: stagnant growth, a rapidly ageing population, one of the world’s lowest birth rates, and lasting impacts from Donald Trump’s trade policies. As the election approaches, the national debate is shifting from the drama of impeachment to the urgent need for sound economic and social policies. The hope is that this vote will mark a turning point—bringing the focus back to solving real problems that affect ordinary lives.

The lineup is set

South Korea’s conservative People Power Party (PPP) confirmed that former labor minister and hardline conservative Kim Moon-soo would be its presidential candidate. He will face Lee Jae-myung of the liberal Democratic Party, who currently holds a strong lead in the polls. Reform Party’s Lee Jun-seok is another candidate, alongside four other contenders, including two independents.

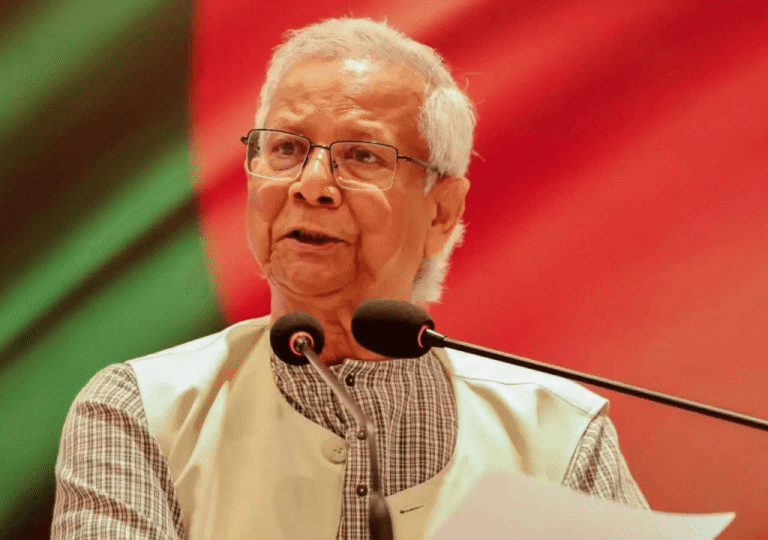

Lee, who narrowly lost to Yoon Suk-yeol in 2022 after a bitter campaign, expressed gratitude to his supporters for standing by him since what he called a painful defeat. He said he was determined to reward their continued support by securing a victory in the upcoming election. While he holds an upper hand, Lee is also dealing with multiple criminal charges—including allegations of bribery and involvement in a $1 billion property scandal. Although he denies all accusations, the courts have postponed further hearings until after the election. But people think he is better than yoon’s team.

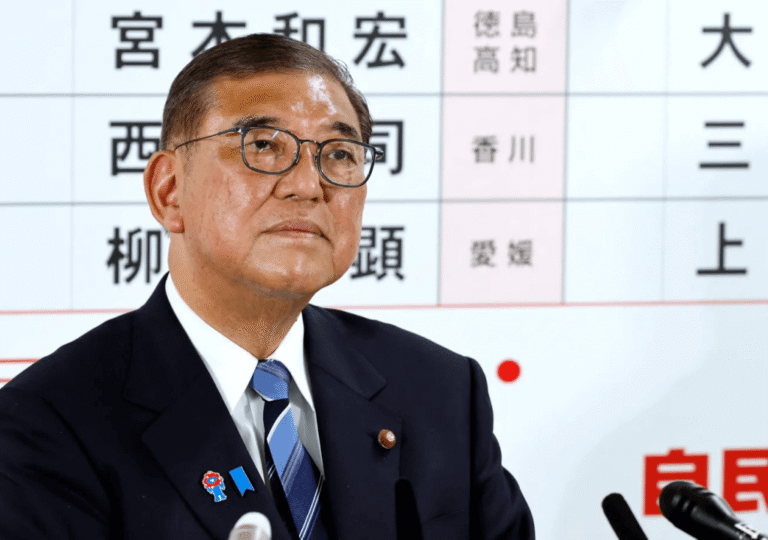

Kim Moon-soo’s nomination has highlighted the deep divisions within the People Power Party (PPP). Although Kim was initially selected in early May, senior party leaders briefly attempted to replace him with former Prime Minister Han Duck-soo, believing Han had a stronger chance of defeating Lee. That move was rejected by party members, who reinstated Kim and warned that further internal strife could make it easier for Lee to win.

Campaigns are heating up

Kim Moon-soo has centered his campaign on reviving South Korea’s struggling economy, addressing rising youth unemployment and a worsening cost-of-living crisis. While remaining committed to conservative principles, he has sought to distance his party from the instability caused by Yoon Suk-yeol’s controversial suspension of civilian rule. At his campaign launch in a Seoul market, Kim emphasized his intention to be a president focused on the people, their livelihoods, and economic recovery.

If elected, Kim has vowed to immediately pursue a summit with Donald Trump to renegotiate trade tariffs. He also promises a hardline approach to North Korea, while pledging to create a more business-friendly environment, encourage private investment, and expand housing support for young people and newlyweds.

Lee Jae-myung, Kim’s main rival, has been campaigning under heightened security measures, including wearing a bulletproof vest, after Democratic Party lawmakers received warnings of a potential assassination plot. The threat is believed to have come from former operatives of a covert military unit that operated during South Korea’s authoritarian period from the 1960s to the 1980s.

Lee, who was stabbed in the neck during a press event in January 2024, has said the need for such precautions reflects how fractured South Korean society has become—where even a presidential candidate must campaign in protective gear.

His campaign focuses on driving economic growth through advancements in artificial intelligence and the global success of Korean pop culture, which fuels both exports and tourism. He also proposes tax incentives to boost the nation’s declining birth rate.

Consistent with previous liberal candidates, Lee has pledged to reopen dialogue with North Korea, despite its advancing nuclear program and increasing military alignment with Russia.

South Korea is in need of a true leader

Beyond party lines, South Korea now needs a true leader—someone the people can rally behind. The country is facing serious challenges across all sectors. Beneath the glamour, deeper issues are surfacing. A capable leader is no longer just desirable—it’s essential. If that leader can work in alignment with the parliament, South Korea has a real chance at restoring political stability.

The next president won’t just inherit a divided government—they will inherit the responsibility of restoring institutional trust, reviving the economy, and navigating an increasingly unstable global environment.

South Korea now stands at a crossroads—either choose the best, or risk deeper decline.