China’s efforts to assert control over the entire South China Sea have provoked strong resistance from neighboring Southeast Asian nations. Repeated incidents—such as military drills and naval collisions—continue to heighten the risk of open conflict. These provocations fuel nationalist sentiment and strain diplomatic relations. Although many Southeast Asian countries remain economically reliant on China for trade and investment, rising tensions have bred distrust and resentment.

For years, the countries involved in the dispute have called for a binding Code of Conduct to manage tensions and promote maritime stability. However, despite recurring discussions in regional forums, meaningful progress remains elusive.

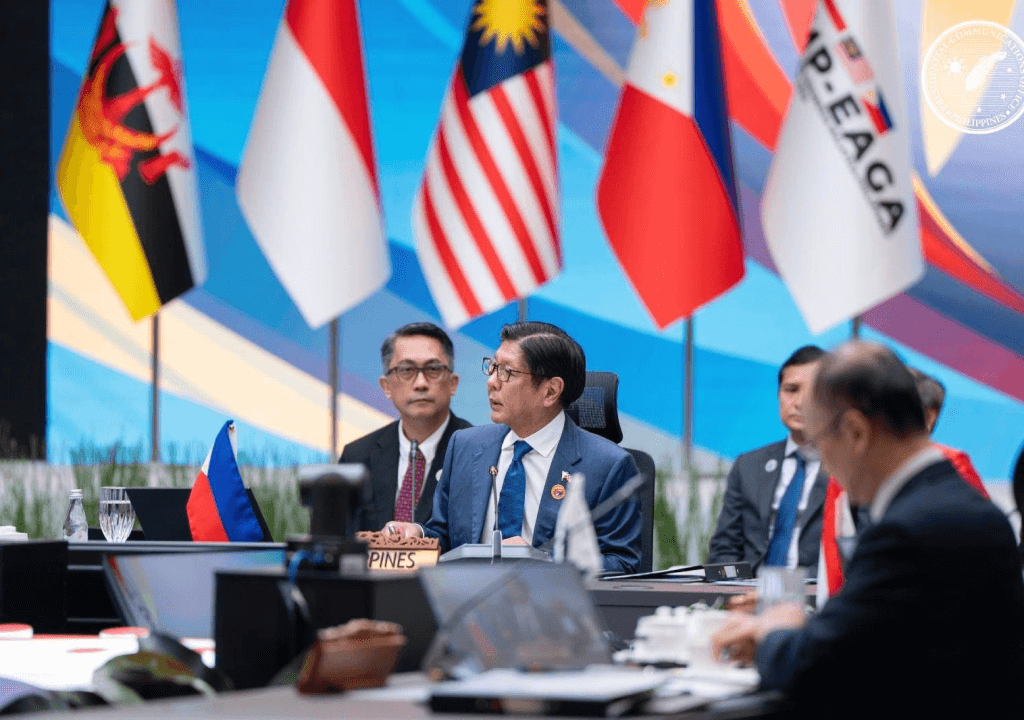

The issue recently returned to the spotlight when Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. renewed calls for such a code during the latest ASEAN Summit, which brought together Southeast Asian nations with stakes in the dispute—alongside active participation from China.

The much-needed code of conduct

At the latest edition of ASEAN Summit, Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos Jr., whose country remains especially exposed to China’s aggressive moves in the South China Sea, called on Southeast Asian leaders to accelerate the adoption of the long-stalled Code of Conduct. As China’s regional influence grows and it positions itself alongside ASEAN against U.S. tariffs, Marcos aimed to confront the threat head-on. He emphasized the need for a legally binding agreement to protect maritime rights, ensure regional stability, and prevent dangerous miscalculations at highly contested seas.

Marcos’s call came just days after the ASEAN Maritime Security 2025 Forum convened in Manila, where more than 70 maritime experts, government officials, and academics from the 10 ASEAN member states gathered between May 21 and 23 to address regional maritime security challenges. At the forum, Malaysia’s Deputy Director General of the National Security Council, Hamzah Ishak, expressed cautious optimism that the Code of Conduct could be finalized by next year, when the Philippines assumes the rotating ASEAN chairmanship. He noted that the draft has already reached its third or fourth reading and, while progress is slow, he voiced hope that both the Code and regional maritime law enforcement frameworks will advance during the Philippines’ leadership.

Hamzah also emphasized the importance of clarifying key legal concepts—such as a common interpretation of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea and a consistent definition of Exclusive Economic Zones. He further cautioned against involving external adjudicators, arguing that third-party interventions rarely produce outcomes that benefit all parties. His comments reflected broader regional concerns over the growing involvement of external powers like the United States and Japan—both allies of the Philippines—whose presence in the region is framed as a commitment to safeguarding freedom of navigation and protecting ASEAN partners from increasing pressure from Beijing.

Skepticism around

Negotiations over the Code of Conduct between ASEAN and China—ongoing since 2002—have repeatedly stalled due to persistent tensions over territorial claims and clashing national interests. Many experts believe ASEAN’s consensus-based approach lacks the strength to push a dominant China toward accepting any binding agreement. At a recent maritime forum in Manila, analysts predicted that even if a deal is reached, it is likely at least a decade away.

A poll taken during a panel discussion on ASEAN’s consensus-driven decision-making revealed deep skepticism. Only one participant believed the Code could be finalized within three years. Eighteen predicted it would take a decade, while a majority—28 participants—said the agreement would never materialize.

China’s stance remains the greatest uncertainty. Although Beijing initially rejected the idea of a binding agreement, it now supports one—largely because it would formalize its sweeping claims in the South China Sea. Meanwhile, political divisions within Southeast Asia persist, with China wielding considerable influence in several member states.

For real progress to happen, ASEAN must first bridge the gap between its mainland and maritime members and conduct thorough internal consultations to forge a united front.

Will it work out?

Although Southeast Asian politicians continue to discuss the Code of Conduct, the current situation offers slim chances for its implementation. China’s expansionist ambitions and non-negotiable claims in the South China Sea make it difficult. This became evident in 2016, when an international arbitral tribunal in The Hague ruled in favor of the Philippines, declaring that the People’s Republic of China’s claims—based on historical maps from imperial China—had no legal basis under international law. China rejected the ruling, continues to assert its claims, and actively reinforces its control over the contested waters, resisting any agreement that could limit its dominance.

Despite these obstacles, the Philippines continues to push forward. President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. has renewed calls for the Code of Conduct as part of a broader effort to keep the issue on the regional diplomatic agenda and to push back against ASEAN’s growing tilt toward China.