As global inflation continues and the yen stays weak, the cost of living in Japan is steadily rising—especially for essentials like rice, which has nearly doubled in price over the past year. With wages stagnant, many households are feeling the strain. The once stable, if sluggish, economy now feels fragile and uncertain.

Rising public unease is clearing a path for political extremes. As daily struggles mount, resentment is increasingly directed toward immigrants. Discontent over immigration, mass tourism, and rapid cultural change is growing, especially among lower-income groups hit hardest by inflation. Much of this frustration is now aimed at the long-ruling Liberal Democratic Party, which many see as out of touch with everyday life. Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba, leading a fragile coalition without a clear majority, is steadily losing public trust. Seizing the moment, the far-right Senseito party is rising as a powerful voice for those demanding bold and disruptive change.

All attention is now on the House of Councillor election scheduled for July 20. It will be a crucial test for Ishiba’s leadership—and a potential breakthrough for the far-right Senseito party, which promises bold change to a disillusioned electorate.

The rise of the Senseito

Emerging from YouTube streams at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic—where it trafficked in conspiracy theories about vaccines and a shadowy global elite—Sanseito has rapidly transformed from an online curiosity into the most prominent voice of Japan’s far right. Now, as the nation prepares for Sunday’s upper house election, the party is gaining momentum and reshaping the political conversation.

Once dismissed as fringe internet activism has found a receptive audience among disillusioned voters, especially the young and politically disengaged. Many are first-time voters who feel alienated by decades of economic stagnation and a political establishment they see as complacent and out of touch.

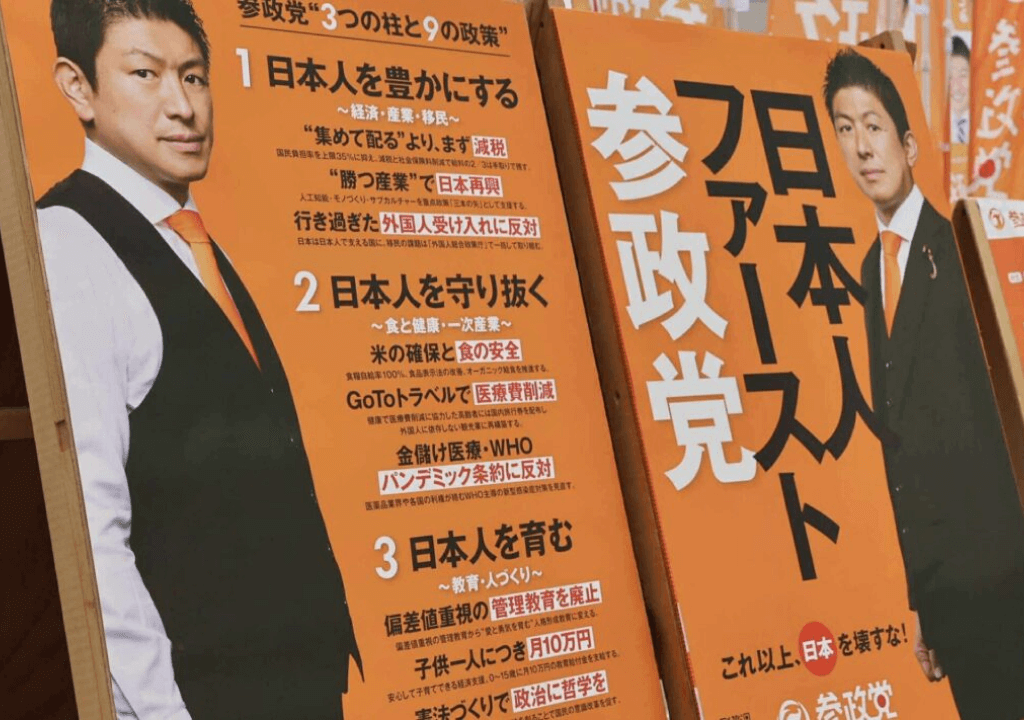

Sanseito’s message is fiercely nationalist and socially conservative. In contrast to the ruling Liberal Democratic Party’s center-right posture—often viewed by critics as increasingly compromised—Sanseito offers an uncompromising alternative. Its platform calls for a “Japan First” approach: reinstating traditional family values, repealing the LGBT Understanding Promotion Act, enforcing strict immigration controls, and offering generous monthly child benefits of ¥100,000 (approximately $670) to Japanese families, while ending welfare support for non-citizens.

What was once considered politically taboo—anti-foreigner sentiment—is being expressed more openly by Senseito. Among its growing base, the party is seen as bold, authentic, and unafraid to challenge long-standing norms.

Though polls suggest Sanseito may secure only 10 to 15 of the 125 seats up for election, its influence is being felt far beyond those numbers. Its growing popularity is weakening Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba’s already fragile minority government, which now relies on opposition cooperation to stay afloat. Analysts suggest that a poor showing by conservative yet named liberal, the ruling Liberal Democratic Party, and a strong performance by Sanseito may solidify its role as a defining force in Japan’s political future.

Deepening nationalist fervor

The leader of the Sanseito party, Sohei Kamiya—a former supermarket manager and English teacher—has drawn attention for adopting a confrontational political style that observers say closely resembles that of former U.S. President Donald Trump. His rhetoric and posture have prompted comparisons to far-right, anti-immigration parties in Europe, such as Germany’s Alternative für Deutschland (AfD).

Kamiya has expressed strong animosity toward the political left, asserting that in the past, discussions around immigration were immediately shut down by left-leaning critics. He acknowledged that his party is now also receiving backlash for its views, but insisted that it is simultaneously gaining growing public support. Like many far-right movements globally, Sanseito promotes alternative narratives and perspectives, often presenting its own interpretations to support its views.

Sanseito’s emergence coincides with Japan’s recent relaxation of its traditionally strict immigration policies. In response to an increasingly severe labor shortage driven by a shrinking and aging population, the government has opened more pathways for foreign workers. As a result, the number of foreign-born residents reached a record 3.8 million in 2024—roughly 3 percent of the national population. Although this figure remains small compared to the United States and Europe, it has sparked unease in a society that places high value on cultural uniformity and social cohesion.

Sanseito and Kamiya have tapped into these anxieties by advocating the view that Japan should solve its demographic and economic challenges without increasing immigration. The party warns of what it describes as “foreign colonization” and maintains that the nation should be governed solely by and for Japanese people.

Sanseito has also gained momentum through the strategic use of social media, where both factual content and misinformation circulate widely. A recurring falsehood claims that one-third of welfare recipients in Japan are foreign nationals—a figure repeatedly debunked but still widely shared.

Such narratives are bolstered by frequent media coverage of crimes involving immigrants and tourists. Meanwhile, viral videos depicting foreign visitors and residents allegedly disregarding local customs—such as littering or behaving in ways seen as culturally inappropriate—have intensified perceptions of social and cultural tension.

Adding to the unease are mounting concerns over land purchases by wealthy Chinese investors, often depicted as subtle encroachments on Japan’s sovereignty. In some circles, these acquisitions are framed as a strategic threat tied to the Chinese Communist Party.

Collectively, these narratives—circulating widely on social media, reinforced by selective news coverage, and leveraged by opportunistic political actors— are accelerating the normalization of hardline ideologies and clearing a path for what many now see as a uniquely Japanese iteration of Trump-style populism.

What comes next?

As Japan prepares to vote for just over half of the 248 seats in the House of Councillors—the upper chamber of the Japanese parliament—the stakes are high. Prime Minister Ishiba’s LDP, in coalition with the Komeito party, needs to secure at least 50 of those seats to retain a majority. However, with the LDP’s approval ratings continuing to fall, even this modest target may prove difficult to reach.

A strong showing by Sanseito—particularly if it secures 20 or more seats, as the party aims—could mark a turning point in Japanese politics, signaling a significant realignment within the conservative camp. In the last House of Representatives election, Sanseito, despite its relatively small size, managed to gain seats even as other conservative parties saw declines—a trend that may now be accelerating.