Myanmar’s generals, who toppled the country’s elected government and drove the nation into nearly five years of civil war, now insist they are ready to hold elections as a step toward restoring civilian rule.

But with major parties banned, new laws tilted to favor military-backed allies, and vast areas still beyond the junta’s control, doubts are growing over what these elections truly mean. For many, they resemble not a path out of crisis and toward democracy, but another effort by the generals to claim legitimacy while tightening their grip on power.

The plan has been welcomed by China, Russia, and India, even as opposition groups and Western governments voice deep skepticism.

Preparations Begin

As part of its move toward a December 2025 election, Myanmar’s junta has formally ended the state of emergency and begun preparing to fill seats in the Amyotha Hluttaw (House of Nationalities) and the Pyithu Hluttaw (House of People’s Representatives) of the Assembly of the Union.

The military introduced a new electoral law in 2023, drawing sharp criticism for tightening party registration rules, barring individuals with criminal convictions, including Aung San Suu Kyi and Win Myint, and replacing the first past the post system with proportional representation. Analysts say the law is clearly designed to strengthen the military’s proxy, the Union Solidarity and Development Party, which performed poorly in the 2020 general election, leaving opposition parties with little chance of mounting a credible challenge.

Major opposition parties remain sidelined. The National League for Democracy, removed from power in the 2021 coup, refused to register under the new law and was formally dissolved in March 2023. The Shan Nationalities League for Democracy, the country’s second largest opposition party, also opted out.

With 25 percent of parliamentary seats set aside for the military, the shift to proportional representation nearly ensures the junta will retain control with just over a third of the popular vote. Officials are expected to introduce further measures to secure the election’s “success,” following a law allowing prison sentences of up to 10 years for speech or protests deemed to challenge the process.

Election Amid Civil War

Myanmar remains deeply divided, with multiple armed groups controlling large swaths of territory and many refusing to cooperate with the junta. A national census conducted last year failed to collect data from 19 million of the country’s 51 million people, citing “significant security constraints.” The gap underscores the limited reach of any election, and analysts warn that resistance groups could launch offensives around the polls to reject the process entirely.

Although the junta has reportedly regained some ground after earlier setbacks, resistance fighters continue to hold key areas outside military control. Over the past year, the army has invested heavily in drone technology to counter opposition forces, who have themselves used drones effectively in combat, raising the risk of further escalation.

Under these conditions, it remains unclear how many citizens will take part in an election restricted to parties sanctioned by the military.

Why the Junta Wants an Election

Since the 2021 coup, Myanmar’s generals have repeatedly promised elections to appease the public, while repeatedly postponing them as the conflict worsened. But a collapsing economy and mounting pressure from neighboring countries affected by the war’s spillover have forced the military to act.

The economy is on the brink of collapse, with textile factories shutting down and gas reserves dwindling. Analysts say the elections are intended to provide enough legitimacy to lure investors back.

China, India, and Russia have signaled readiness to invest if stability is restored. China, in particular, has repeatedly urged the generals to hold elections, seeing even superficial polls as the only viable path forward. Beijing views the elections as crucial to protecting its economic and strategic interests, including a multibillion-dollar corridor linking China to the Indian Ocean. Both China and Russia are expected to endorse the results.

There is also hope that the polls might weaken resistance alliances and encourage economic recovery. The junta has offered cash rewards to fighters willing to lay down their arms.

Will the December Election Happen?

Whether the December elections will actually take place remains highly uncertain. Analysts warn that armed groups may intensify fighting to prevent the polls, and several factions have already pledged to reject any results.

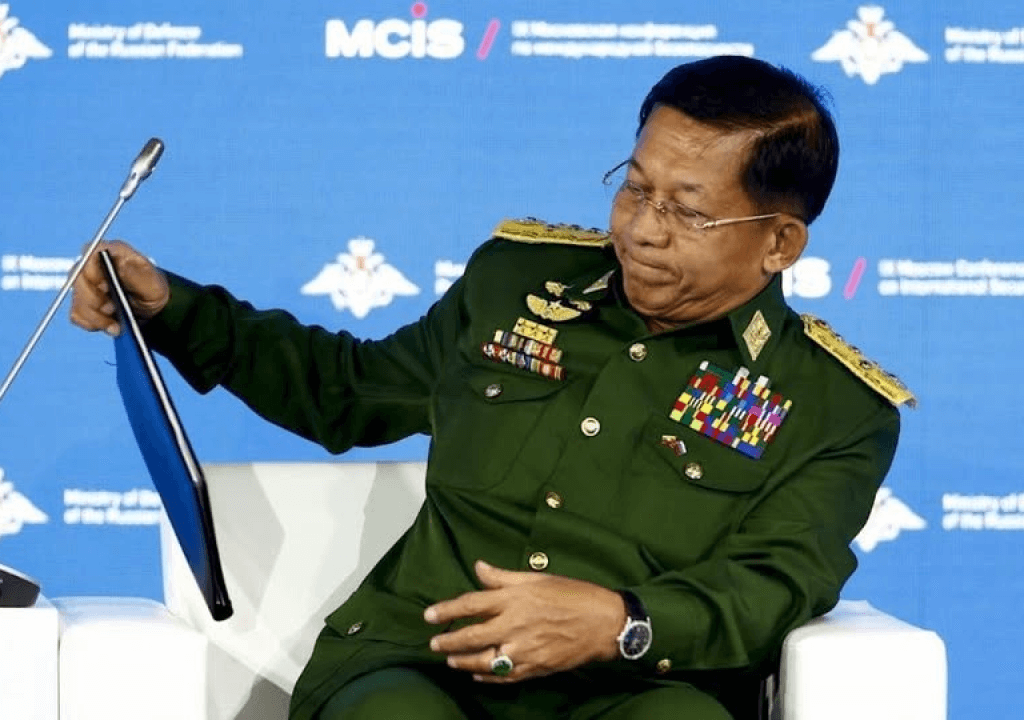

Min Aung Hlaing initially promised elections by August 2023, but repeated delays followed as violence surged across the country. The state of emergency, declared by Acting President Myint Swe and extended seven times, finally expired on July 31, 2025. Myanmar’s constitution requires elections to be held within six months of that expiration, though extensions remain possible.

Even if the polls take place, most observers expect little real competition, drawing parallels to the tightly controlled elections in Russia and Belarus.