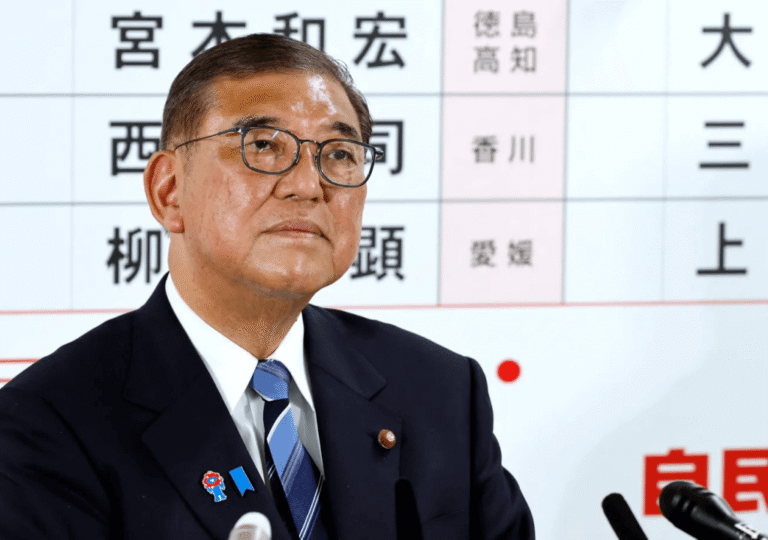

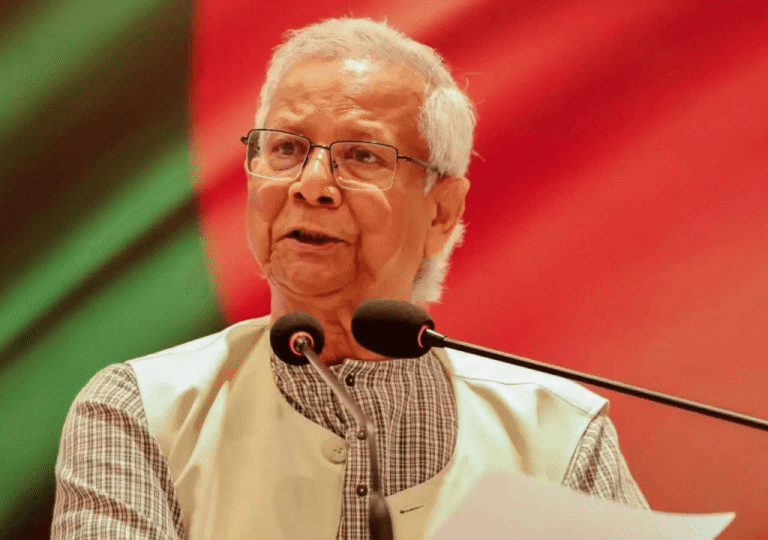

Bangladesh is moving toward a general election on 12 February, an attempt to restore an elected parliament and government after years of upheaval under the interim administration of Prime Minister Muhammad Yunus. The country reaches this moment politically bruised and deeply divided. Competing strands of Islamic politics, ranging from relatively moderate to openly hardline, are vying for influence in a landscape where many familiar political anchors have disappeared.

The Awami League, long the dominant force in Bangladeshi politics, has been barred from political activity. Its leader and former prime minister, Sheikh Hasina, is living in exile under a death sentence. Khaleda Zia, another towering figure who once defined the country’s political rivalry, is no more. Her son has entered politics but remains untested, even as a host of new political players seek to fill the vacuum left by the old order.

Yet even amid the tension, political bans, and a persistent sense of disorder, Bangladesh is moving forward with the formal rituals of democracy. The election is intended to place power back in the hands of voters, and it will test whether the country can finally break free from its recurring cycle of political upheaval.

An Election Without the Awami League

In the first general election since Sheikh Hasina fled to India, most major parties are expected to compete. The Awami League, long the dominant force in Bangladeshi politics, once claimed more than 10 million workers and won the previous four elections. It remains suspended and will not take part.

In the aftermath of the upheaval that forced Hasina’s departure, thousands of Awami League members were driven into hiding or fled abroad, amid mob violence and mounting criminal cases linked to abuses under the former regime. More than 600 party figures eventually sought refuge in Kolkata, the Indian city closest to the Bangladeshi border, where many remain out of public view.

Today, the Awami League is largely absent from Bangladesh’s political landscape. Those associated with the party have been pushed out of public life, along with the secular Bengali nationalist tradition it long represented.

That absence has reshaped the election into what many describe as a bipolar contest. The race has narrowed to the Bangladesh Nationalist Party, often seen as a relatively mild Islamist force, and an 11 party alliance led by the hardline Islamist Jamaat e Islami alongside the National Citizen Party. While the contest is cast as a choice between restoration and change, both camps share a deep hostility toward the Awami League and Sheikh Hasina, raising questions about whether this moment marks the end of the party’s role in Bangladesh’s politics.

The Debate Over Participation and the Ban

Even as the Awami League became politically untouchable, calls grew for its complete removal from Bangladesh’s political space, exposing sharp divisions over whether the party should be allowed to contest the election at all.

Some senior figures argued against an outright ban. Ruhul Kabir Rizvi of the Bangladesh Nationalist Party and Jatiya Party leader G M Quader both supported allowing the Awami League to participate. The army chief, Waker Uz Zaman, reportedly warned that excluding the party entirely would undermine the credibility of the vote. He suggested that a reconstituted Awami League, led by figures with relatively clean reputations such as Shirin Sharmin Chaudhury, Sheikh Fazle Noor Taposh, and Saber Hossain Chowdhury, was necessary to ensure an election that was free, fair, and inclusive.

That view was firmly rejected by others within the interim setup. Members of Students Against Discrimination in the government, including Mahfuj Alam, opposed any role for the Awami League. Nahid Islam, leader of the National Citizen Party, said the party could not return to politics unless its leaders were first put on trial for the July massacre. He argued that any attempt to relaunch a sanitized version of the Awami League would amount to foreign interference. Jamaat e Islami’s ameer, Shafiqur Rahman, echoed that position, opposing the party’s participation outright.

Student agitators also moved the courts, filing a petition seeking a ban on the Awami League and its Grand Alliance partners. The Appellate Division rejected the plea. But pressure continued to build on the streets. On April 9, 2025, the National Citizen Party, Jamaat e Islami, and other Islamist groups, including Hefazat e Islam Bangladesh, organized the Shahbag protest outside the Jamuna State Guest House, the residence of the chief adviser, demanding a formal ban.

A day later, the interim government acted. Citing the Anti Terrorism Act of 2009, it banned the Awami League and all of its activities, both online and offline, and barred the party from contesting or campaigning in the February 12 election.

Minority Politics and the Vacuum Left Behind

The Awami League has long been identified as a pro India party that prioritized Bengali nationalism over Islamic politics, a position that set it apart from Islamist movements in Bangladesh and across the region. That stance earned it sustained support from the country’s Hindu and secular communities. Its removal from politics has created a vacuum that few other parties are able to fill.

With the Awami League absent from the 2026 election, both the Bangladesh Nationalist Party and Jamaat e Islami have moved to court Hindu voters. The BNP has pledged to establish a special tribunal and a dedicated security cell to prevent communal violence against religious minorities, and it has nominated two leaders from the Vishwa Hindu Parishad as candidates.

Whether minority voters believe the BNP can provide the level of protection once associated with the Awami League remains uncertain. Some view the outreach as a tactical move, driven less by conviction than by anxiety over Jamaat e Islami, which has openly advocated the introduction of sharia law in Bangladesh. Many secular voters and Bengali nationalists appear to be making a similar calculation, shifting their support to the BNP as the strongest nationalist alternative to Islamist forces.

Hasina’s Strategy From Abroad

Sheikh Hasina shows no sign of stepping away from politics. A veteran of Bangladesh’s unforgiving power struggles, she has dismissed the verdict against her as a fabrication and rejects the notion that her long career has reached its end. From exile in India, she has begun openly laying the groundwork for a return, including efforts to mobilize supporters to challenge and disrupt the coming election.

Operating from a heavily guarded and undisclosed location in New Delhi, Hasina spends her days in marathon meetings and phone calls with party loyalists inside Bangladesh. According to aides, she remains deeply involved in the party’s internal deliberations, directing strategy from afar.

She delivered her first address from exile to a packed gathering in Delhi through an audio recording that spread quickly among supporters. Speaking from what party officials described as a bunker, she denounced the election and accused Muhammad Yunus of forcibly seizing power and turning Bangladesh into a blood soaked country.

Senior party figures, including former cabinet ministers and members of parliament, are regularly summoned from Kolkata to meet Hasina and refine strategy. Among them is Saddam Hussain, the president of the Awami League’s student wing, the Bangladesh Chhatra League.

“Our leader Sheikh Hasina is in constant communication with our people in Bangladesh,” Hussain said. “Party activists, grassroots leaders, professionals. She is preparing the party for the next struggle.”

The interim government has designated the Bangladesh Chhatra League a terrorist organization. He said Hasina often remains on calls or in meetings for 15 or 16 hours a day. “She is very hopeful,” he added. “We believe she will return to Bangladesh as a hero.”

Awami League leaders accuse Yunus, long viewed by Hasina as a rival, of pursuing a personal vendetta. Yunus has rejected those claims.

“We are telling our workers to stay away completely,” said Jahangir Kabir Nanak, a former Hasina minister. “No campaigning, no voting. This is a sham process.”

At a rally in Dhaka on September 5, organized by Students Against Discrimination to mark one month since Hasina’s ouster, demonstrators demanded accountability. As mob violence swept parts of the country, often justified by supporters as retribution for the abuses of her rule, the Awami League claims that hundreds of its workers were attacked, killed, or jailed without bail. Many remain in hiding.

The persistence of these networks suggests that Hasina still retains a measure of support inside Bangladesh. “We are not in Kolkata because we fear prison,” Hussain said. “We are here because if we go back, we will be killed.”

In the crowded food courts of Kolkata shopping malls, over black coffee and Indian fast food, exiled Awami League politicians continue to gather quietly, mapping out what they hope will be a path back to power.

A Politics Where Anything Is Possible

Exiled Awami League leaders argue that the new government’s failure, like that of many administrations before it, could reopen the door for Sheikh Hasina’s return. Their strategy rests on the belief that the upcoming election will collapse, failing to deliver either peace or stability, and that public disillusionment will eventually drive voters back toward the Awami League.

They point to Bangladesh’s political history as evidence that governments rarely endure without sliding into authoritarianism. When such systems unravel, power seldom changes hands smoothly. Parties are banned, leaders are pushed into exile, and, over time, comebacks follow. Political exiles, they contend, often return stronger than before.

In Bangladesh’s turbulent political landscape, nothing is ever truly impossible.