South Korea Reinstates Han Duck-soo After Impeachment Rejected

South Korea’s acting president, Han Duck-soo, has been reinstated after the court struck down his impeachment, marking a swift political turnaround.

South Korea’s acting president, Han Duck-soo, has been reinstated after the court struck down his impeachment, marking a swift political turnaround.

Israel is embroiled in a deepening political crisis as legal battles and courtroom fights intensify, testing the government’s stability and sparking nationwide debate.

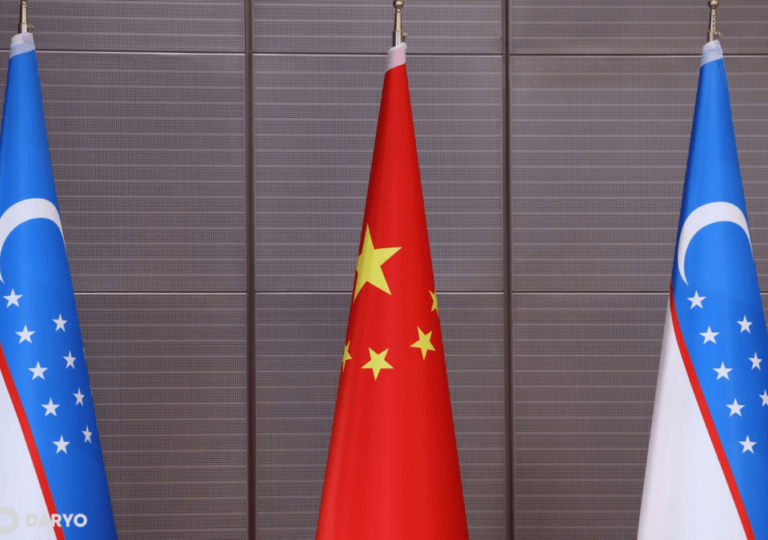

China's influence in Uzbekistan is growing through investments, infrastructure, and diplomacy. But is Beijing gaining too much control? Many Uzbeks on social media are concerned.

As regional tensions rise, Singapore and Vietnam are strengthening their diplomatic and economic partnership, fostering greater cooperation in Southeast Asia

As tensions rise with Yemen, could it become the next major conflict involving the U.S.? Explore the shifting dynamics, key players, and the potential for escalation in the region.

Progress Singapore Party revamps its leadership in preparation for the upcoming election. Explore what this means for Singapore’s political landscape.

Indonesia has passed a controversial law expanding the military’s role in government, raising concerns over democratic backsliding and civilian oversight.

Is Syria’s new constitutional declaration truly inclusive, or does it mask deeper divisions? Explore the challenges and implications of Syria’s evolving political framework.

Myanmar’s junta is moving toward elections, but many fear they will be a farce. Explore concerns over legitimacy, military control, and democratic suppression.

Israel breaks the truce, escalating demands for hostage release. Is Netanyahu acting to rescue captives or to secure his political future?