Indonesia Expands Military’s Role, Raising Fears of Democratic Erosion

Indonesia has passed a controversial law expanding the military’s role in government, raising concerns over democratic backsliding and civilian oversight.

Indonesia has passed a controversial law expanding the military’s role in government, raising concerns over democratic backsliding and civilian oversight.

Is Syria’s new constitutional declaration truly inclusive, or does it mask deeper divisions? Explore the challenges and implications of Syria’s evolving political framework.

Myanmar’s junta is moving toward elections, but many fear they will be a farce. Explore concerns over legitimacy, military control, and democratic suppression.

Israel breaks the truce, escalating demands for hostage release. Is Netanyahu acting to rescue captives or to secure his political future?

Azerbaijan secures a decisive victory as Armenia concedes in a newly signed peace deal. Explore the implications of this agreement and what it means for the future of the Caucasus.

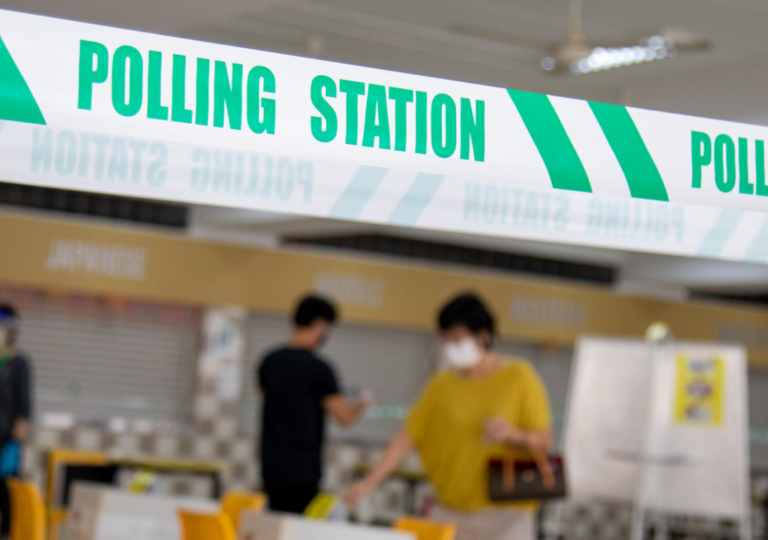

As Singapore’s political boundaries shift, opposition parties rethink their strategies to stay competitive. Discover how they plan to navigate the changing landscape.

Saudi Arabia is stepping onto the world stage as a key diplomatic player, mediating global conflicts and expanding its influence beyond the Gulf. Is the kingdom the next great power broker?

Discover how new rail routes in Central Asia are strengthening Kazakhstan’s strategic importance, enhancing trade, and redefining regional influence.

Singapore has revised its electoral boundaries in preparation for the general election. Learn why there is a growing call for clearer and more understandable demarcations.

The Syrian government and the Kurdish-led SDF have struck a deal to integrate the northeast. What does this mean for Al Sharra’s leadership and his government’s future?