After months of mounting pressure, Bangladesh’s interim government announced on Friday, June 6—just a day before the Muslim festival of Bakrid—that the next general election will be held in the first half of April 2026.

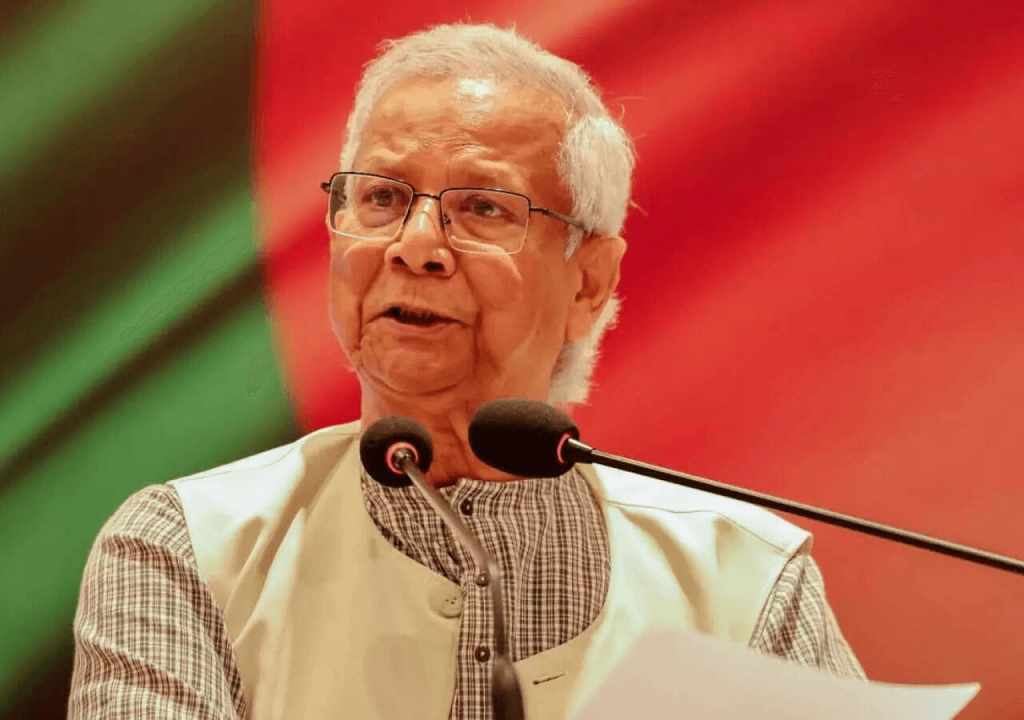

The announcement comes amid mounting criticism of Muhammad Yunus and the interim administration. Former opposition parties and Islamist groups have voiced strong dissatisfaction, accusing the government of deliberately stalling the democratic transition. Initially expected to govern for only a few months following the ousting of Sheikh Hasina’s government in August last year, the interim leadership will now remain in power until the election in April—extending an unelected rule that many view with growing concern.

Meanwhile, Bangladesh is facing an escalating ideological struggle, mirroring conflicts seen across much of the Islamic world—a widening divide between fundamentalist and radical forces on one side, and liberal reformists on the other. As political tensions deepen, many observers view the announced election timeline as a calculated attempt by Yunus to relieve pressure and preserve the country’s fragile political stability.

An Extended Transition

Yunus stated that the country’s Election Commission would unveil a detailed roadmap for the upcoming polls at an appropriate time. While the election timeline may seem distant, he emphasized that adequate preparation and effective execution are crucial. With numerous political factions—from established parties to emerging groups—vying for power, a poorly managed election could plunge the nation into deeper turmoil.

In the months ahead, significant events are expected to unfold, shaping public sentiment across Bangladesh’s vast and restless population. There are growing concerns that even the ousted Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina may regain popular support, as many citizens grow weary of the country’s uncertain trajectory.

Hasina is currently in India and is being tried in absentia by Bangladesh’s International Crimes Tribunal. The charges against her stem from her administration’s violent suppression of protests during the final days of her 15-year rule. Prosecutors allege she ordered the killing of student protester Abu Sayeed, the first casualty of the uprising. Hasina, however, insists the case is politically motivated.

Her party, the Awami League, has been banned pending the outcome of her trial. Last month, the Election Commission suspended its registration, effectively barring it from contesting the next election. Despite this, many of its members continue to operate—either under new names or through quieter, more covert means. Their activities are expected to provoke counter-movements from other political forces.

Meanwhile, Islamist organizations such as Jamaat-e-Islami, a group aligned with the Muslim Brotherhood are gaining ground. Highly religious and unwilling to wait indefinitely, their rising influence could reshape the country’s political landscape. On the other side, leftist student groups are also unlikely to remain passive.

The year ahead promises a turbulent stretch, as rival forces maneuver for influence and legitimacy. The long wait until April 2026 is not merely a countdown to an election—it is a volatile period in which the future of Bangladesh will be contested on multiple fronts.

The Opposition Isn’t Pleased

Opposition parties—including the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP)—have consistently called for a clear and firm timeline for a democratic transition since the ousting of Sheikh Hasina’s government in August last year. But now further extension causes deep frustration in the BNP. Salahuddin Ahmed, A member of the party’s Standing Committee, criticized the government for repeatedly announcing reform phases without implementing meaningful changes. He questioned the purpose of yet another inauguration ceremony and dismissed the latest round of reforms as superficial, accusing the administration of merely combining old ideas and presenting them as new solutions—a symbolic gesture he mockingly described as offering a ‘banana of reforms.’

In response to the criticism, Chief Adviser Muhammad Yunus has invited opposition parties for a fresh round of talks scheduled for tomorrow.

BNP spokesperson Ruhul Kabir Ahmed responded by reiterating the party’s demand for the interim government to consolidate the outcomes of previous discussions and present them publicly. He argued that the government’s repeated ceremonies, such as the June 2 inauguration of the third phase, were merely ritualistic and lacked substantive progress. According to him, the approach has become increasingly performative and ineffective.

The BNP is not alone in its discontent. Other opposition factions are also voicing concern, and dissatisfaction with the interim government’s handling of the political transition.

What Happens Next?

If the election timeline stays as planned, Bangladesh still faces nearly ten months under interim rule. The BNP—long the main opposition force with historical links to Pakistan and a platform grounded in Islamic conservatism—appears well-positioned for a return to power. Yet, party leaders are uneasy. They fear that, in the months ahead, shifting political dynamics and unexpected developments could erode their support base. This concern fuels their frustration over the delayed election schedule. Though not inclined toward a coup, the BNP is expected to step up efforts to push for an earlier vote.

Meanwhile, both Islamist and leftist factions—each with a strong grassroots base—are working to establish themselves as credible political alternatives. These groups may eventually compete with or negotiate alongside the BNP for power. The extended timeline could also offer an opening for the Awami League to regroup, possibly with quiet support from India, which has its own interests tied to rising concerns over illegal immigration from Bangladesh. The longer the delay, the more unpredictable and complex the political landscape in Bangladesh is likely to become.