At the Shangri-La Dialogue, a Spotlight on China’s Shadow

China’s absence from ministerial-level talks at the 2025 Shangri-La Dialogue signals a more cautious diplomatic stance amid rising regional tensions.

China’s absence from ministerial-level talks at the 2025 Shangri-La Dialogue signals a more cautious diplomatic stance amid rising regional tensions.

Philippine President Marcos Jr. urges ASEAN to fast-track the South China Sea Code of Conduct amid concerns over China’s growing sway in the regional bloc.

Southeast Asian nations are seeking a unified meeting with Trump to address U.S. tariffs while pushing for greater regional integration. Can ASEAN overcome internal differences to act as one?

The insurgency in southern Thailand has flared up again, raising concerns about escalating violence. Explore the factors driving the conflict and what the future may hold for the region.

The United Kingdom and India have finalized a landmark trade agreement after three years of intense negotiations. The deal is set to boost both economies, fostering new trade opportunities and strengthening bilateral ties.

India carried out cross-border missile strikes against Lashkar-e-Taiba in a decisive retaliation to terrorist aggression originating from Pakistan.

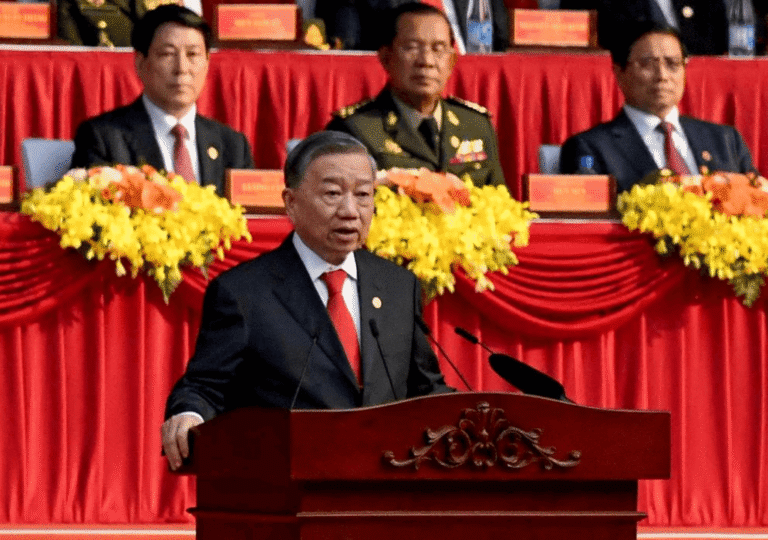

Vietnam reform marks a major shift in governance, with sweeping cuts to bureaucracy and a push for centralized control aimed at boosting efficiency and long-term economic resilience.

As Kashmir violence reignites India-Pakistan tensions, the Indian government maintains a calculated calm. While the media speculates on war, New Delhi opts for restraint and strategic pressure over open conflict.

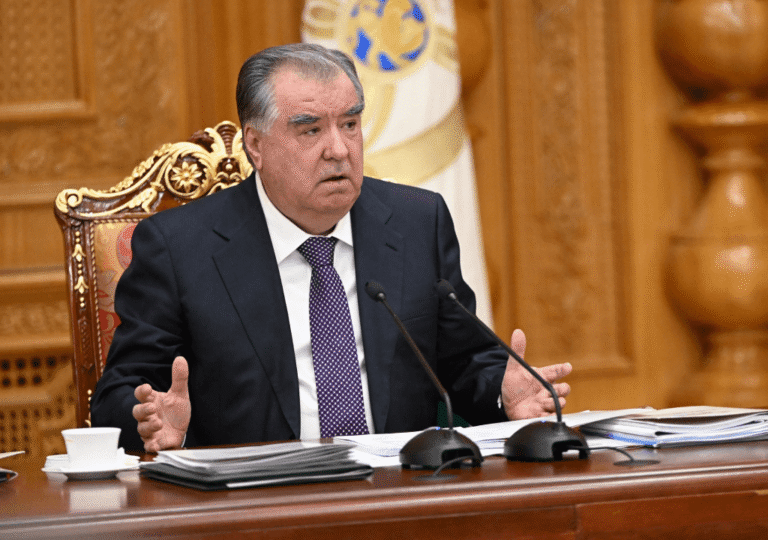

In Tajikistan, President Emomali Rahmon is paving the way for his son Rustam’s ascent to power. With strategic purges and political maneuvering, the country inches closer to a dynastic succession.

Modi and J.D. Vance highlighted promising progress in ongoing trade negotiations, signaling cautious optimism for future economic cooperation.