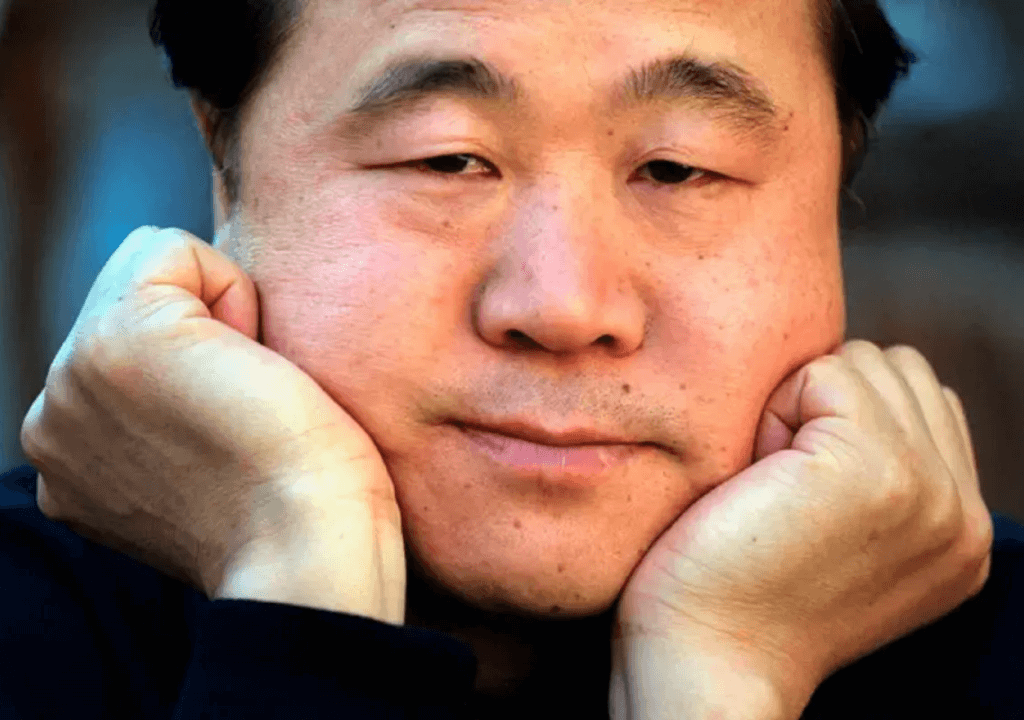

The Nobel Prize stands as a prestigious symbol of recognition, instilling profound pride in nations whose citizens achieve its esteemed honor. However, in China, perceptions diverge sharply. The receipt of a Nobel Prize often ignites skepticism and may lead to social marginalization. This viewpoint reflects the historical tension between the Nobel Foundation and Beijing, with the Foundation often seen as siding with opponents of communist China. Figures like Liu Xiaobo and the Dalai Lama, recipients of the Nobel Peace Prize, symbolize this narrative, suggesting political motives behind the award. While skepticism of this nature is rare in other prize categories, recent reports suggest that even Nobel laureate in literature Mo Yan is not immune to China’s reservations about the Nobel Prize.

Chinese activists have initiated a robust campaign against Mo Yan, the celebrated author also known as Guan Moye, who made history as the first Chinese citizen to receive the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2012. They allege that he sympathizes with historical adversaries and romanticizes past invaders, notably Japanese soldiers who once occupied China. These accusations, disseminated widely on platforms like Weibo, depict Mo Yan as betraying China’s interests, purportedly advancing Western agendas at the expense of national pride.

Mo Yan rose to prominence through his novel “Red Sorghum,” which vividly recounts the saga of three generations of a family in Shandong during the Second Sino-Japanese War, recognized in China as the Chinese War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression. On the other hand, Guan, often likened to China’s Gabriel Garcia Marquez for his adept use of magical realism, emerges as a non-dissident literary figure. As a member of a state-sponsored writers’ association and having served on the country’s premier political advisory body for five years, Guan offers a nuanced depiction of Chinese society in his novels. Despite occasionally critiquing China’s family planning policy, Guan’s works manage to navigate within the confines of Beijing’s established boundaries.

Observers note that Mo Yan has not faced the same level of difficulties as some of his fellow laureates. Unlike the relatively calm trajectory experienced by Guan, the journey of Gao Xingjian, a Chinese-born Nobel laureate in 2000, takes a markedly different path. As a French citizen whose works had been banned in China since the 1980s, he chose not to return to his homeland after openly endorsing the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests, leading to Beijing’s disapproval.

As nationalist fervor intensifies and becomes less accommodating of criticisms in China, Guan has increasingly found himself targeted by nationalist voices on Chinese social media platforms, who accuse him of tarnishing China’s reputation. At first glance, a Nobel laureate author, a bottle of green tea, and Beijing’s Tsinghua University may seem unrelated. However, in recent weeks, they have been dubbed the “Three New Evils” by China’s nationalist netizens in their campaign to uphold the nation’s honor in cyberspace.

Last month, a patriotic blogger named Wu Wanzheng filed a lawsuit against China’s sole Nobel laureate author, Mo Yan, alleging that he disparaged the Communist army and glorified Japanese soldiers in his fictional works set during the Japanese invasion of China. Wu, who uses the pseudonym “Truth-Telling Mao Xinghuo” online, seeks 1.5 billion yuan ($208 million / £164 million) in damages from Mo – equivalent to one yuan per Chinese citizen – along with an apology and the removal of the disputed books from circulation. As of now, his lawsuit has not been accepted by any court.

Over the years, Guan has faced repeated online criticism for both his literary works and his perspectives on literature. However, in the latest surge of dissent, nationalists have accused him of winning the Nobel Prize by highlighting China’s shortcomings and allegedly “Appeasing the West.” Guan’s literary repertoire delves into significant historical events, including the civil war between the Communist Party and the Kuomintang, the Korean War, the intellectual purge under Communist rule, and the Cultural Revolution, which unleashed a decade of political turbulence.

In his 2012 Nobel Prize presentation speech, Per Wästberg, the chairman of the Nobel Committee, commended Guan for his portrayal of the stark brutality of China’s 20th century. Despite being omitted from official Chinese media reports, this acknowledgment has resurfaced recently, seized upon by nationalist online commentators as proof that Guan’s novels malign China. Additionally, critics reference a speech given by Guan in 2005 upon receiving an honorary doctorate from the Open University of Hong Kong, where he asserted that literature and art should expose societal darkness and injustice. However, online detractors argue that Chinese society wasn’t as bleak as depicted in Guan’s novels.

State media outlets have yet to address the controversies surrounding Guan directly, but nationalist commentators have faced criticism without being explicitly named.

While Mo Yan hasn’t directly responded to Wu’s attacks, this week, in light of the “Recent Storm,” Chinese media outlets shared a video of him reciting a poem by the Song dynasty poet Su Shi, reflecting on the challenges and joys of scholarly pursuits despite setbacks.

Experts suggest that the recent criticism reflects a shift towards conservatism in online public opinion within China. Social media platforms have increasingly become hubs for nationalistic sentiments, marked by attacks on perceived “Western Values” and liberal Chinese scholars. This trend has contributed to what some describe as an “Anti-intellectual Culture” online. Despite the prevalence of self-proclaimed patriots, comments expressing contrary views have often been swiftly deleted. Experts attribute these phenomena, at least in part, to economic challenges. The surge in online vitriol has been particularly pronounced since China’s stringent zero-Covid measures confined millions of people to their homes for extended periods, only to emerge into an economy grappling with job scarcity and sluggish demand. In a society where direct protests against the government and authority are restricted, individuals have sought alternatives to express frustration.

And patriotism is the best way to blanket the realities.