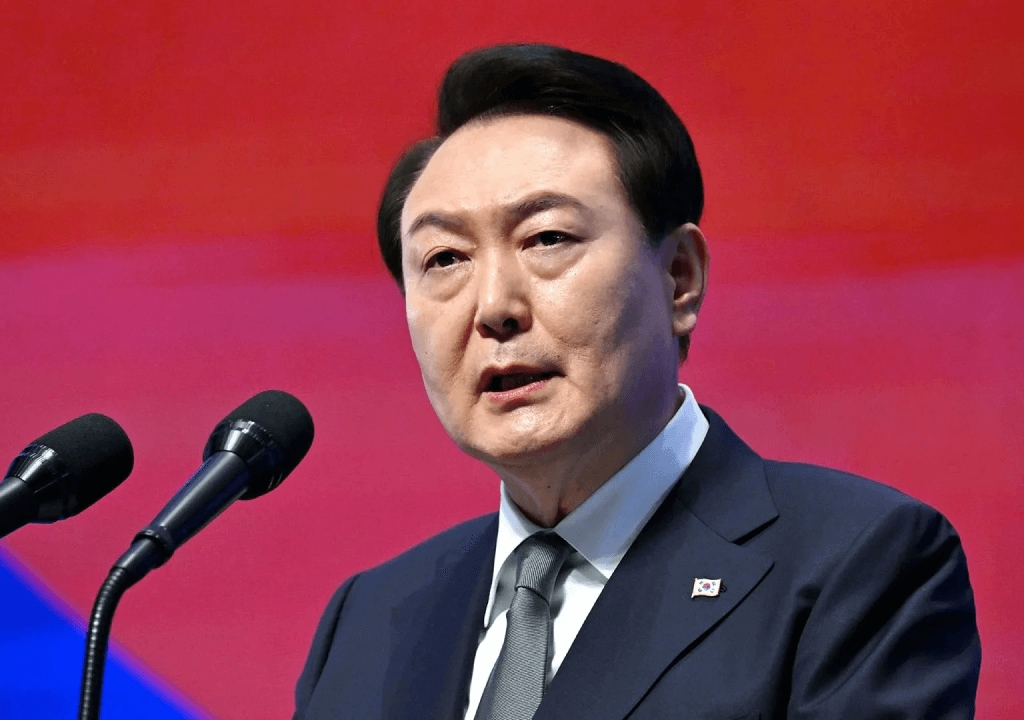

Yoon Yuk-Seoul, still clinging to his role as South Korea’s president, defies persistent calls for his resignation despite being impeached by parliament. Massive protests forced him to retract his abrupt declaration of martial law, and his humiliation deepened when members of his own party joined the opposition in voting for his removal. Yet, Yoon refuses to step down, undeterred by parliament’s decision to strip him of all powers and duties. The nation now turns its attention to the Constitutional Court, tasked with deciding Yoon’s political future. The court must determine whether to remove him from office permanently or restore his authority. Deliberations are underway, but concerns about the court’s impartiality persist, as critics question its alleged ties to the disgraced president. A single favorable ruling could allow Yoon to retain his tenuous grip on power. Beyond the legal and political battles, the streets of South Korea are witnessing an extraordinary display of civic resistance, with protesters demanding not only Yoon’s resignation but also his imprisonment.

On Saturday, thousands of South Koreans poured into central Seoul, amplifying their calls for the removal of suspended President Yoon Suk Yeol. This surge in protest came just one day after parliament’s vote to impeach Han Duck-soo, Yoon’s acting replacement, adding yet another twist to the nation’s spiraling political crisis. Han’s impeachment, driven by his refusal to appoint three judges to the Constitutional Court—the very body tasked with deciding Yoon’s fate—highlighted the chaos engulfing South Korea’s leadership. Neither the people nor the opposition are willing to wait for the Constitutional Court’s decision on Yoon’s impeachment, which must come within its 180-day deadline and looms over the country like a storm cloud. The court’s ruling hinges on critical judicial appointments. If new justices replace the three who stepped down in October at the end of their terms, Yoon’s chances of being found guilty of violating the constitution through his martial law declaration and related actions could rise significantly. However, if the decision is left to the current six judges, the stakes increase dramatically. A unanimous verdict would be required to uphold his impeachment; one dissenting judge would reinstate Yoon

Undeterred by freezing temperatures, South Koreans continue to flood the streets to save their democracy. The protests, which have steadily grown since Yoon Suk Yeol’s failed declaration of martial law on December 3, have transformed Seoul’s historic Gwanghwamun area into a vibrant display of civic engagement. The rallies, blending youthful energy with political urgency, feature protesters carrying K-pop light sticks and banners from civil society groups. Organizers reported that over 500,000 people participated in the latest demonstration, which unfolded under heavy police presence. Marchers called for Yoon Suk Yeol’s imprisonment as they moved from Gyeongbokgung Palace to the busy Myeongdong shopping district, singing along to K-pop music blasting from speaker trucks. The atmosphere, a mix of celebratory fervor and serious political messaging, drew opposition leader Lee Jae-myung, who joined protesters on the ground in a gesture of solidarity. Despite the enormous crowd, the rally remained peaceful and well-organized.

The court building itself has been barricaded by police buses and heavily guarded. Hundreds of flower wreaths, sent by Yoon’s supporters, line the barriers, each bearing messages of support for the suspended president. About a kilometer away from the main demonstration, a large counterprotest led by far-right evangelical Christian groups gathered to oppose the impeachment. Comprising mostly elderly individuals, their tone was hostile as they denounced the parliamentary impeachment votes as invalid and called for Yoon’s reinstatement. Despite this, recent polls show that a majority of South Koreans support Yoon’s removal from office following his attempt to impose martial law earlier this month.

With parliament having done its part, the focus now shifts back to the Constitutional Court. Under normal circumstances, six of the court’s nine justices must approve parliament’s impeachment vote for Yoon to be removed from office, triggering an election to be held within 60 days of their ruling. Han, the impeached acting president who previously served as prime minister under Yoon, steps aside to make way for a temporary successor, finance minister Choi Sang-mok, as parliament moves further down the pecking order to fill the country’s leadership vacuum. Choi, the new acting president, announced on Friday that the government had ordered the military to heighten vigilance and prepare to prevent North Korea from miscalculating the situation and launching provocations.

While the ruling party believes it can extend Yoon’s time in office until the Constitutional Court delivers its verdict, the evolving political landscape has become increasingly unfavorable to both the party and President Yoon. Though they hope to delay the process as public sentiment lightens, the reality is that the situation worsens day by day, with rising anger toward the president and his party, sparking more protests and increasing pressure on Yoon. Nonetheless, he clings to power at any cost, desperately holding onto the presidency. It is clear that the opposition will not allow any further time, with a parliamentary majority ready to oust him. The political crisis will persist until a new presidential election is held, and Yoon is likely to hold on, struggling to maintain his position until then.