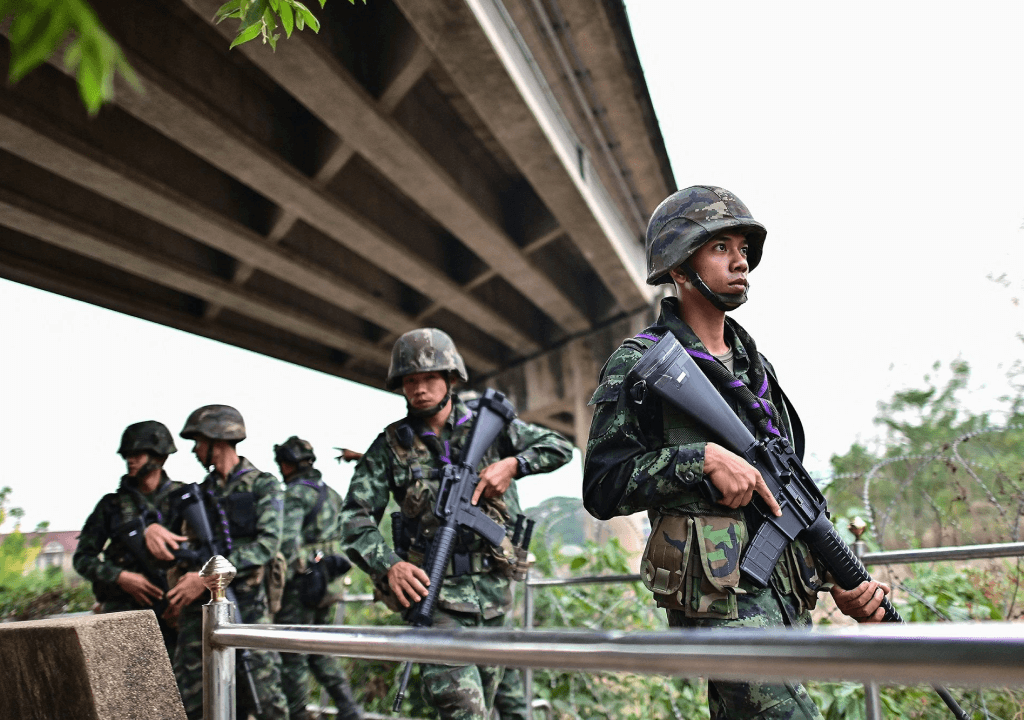

It has been three years since Myanmar witnessed a coup d’état that overthrew the democratically elected government. We all remember the viral video of a girl dancing while military vehicles approached the presidential palace to take control of the state. After three years, the military rule is still in power despite many democratic protests and military opposition. Major democracies around the world expressed concern and introduced tough sanctions in solidarity with democracy. Interestingly, despite Western sanctions, Myanmar, unlike resource-rich Russia, has managed to sustain itself. This has raised doubts about neighboring countries helping the junta by staying neutral. These suspicions were cemented by a recent United Nations-sponsored investigation revealing that Thailand has emerged as the leading source of banking services for Myanmar’s military junta and a key financial conduit for procuring arms and other military equipment.

Tom Andrews, the U.N. special rapporteur on human rights in Myanmar, authored a report detailing the military junta’s adaptive strategies amidst sanctions from foreign governments. It describes how the State Administration Council (SAC), Myanmar’s military leadership, has altered financial and military suppliers to sustain arms procurement and its opposition campaign. The report identifies that despite international sanctions, SAC maintains crucial banking ties, with 16 banks across seven countries processing military transactions, and 25 banks providing correspondent services to Myanmar’s state-owned banks since the coup. Andrews highlights a significant shift in arms procurement, noting a decline in formal banking system transactions to $253 million in 2023 from $377 million the previous year, particularly citing decreased Chinese arms transfers from $140 million to $80 million. An interesting part of the report is how Thailand, which remains neutral and has not condemned the military takeover of the regime, has emerged as the major source for military supplies, surpassing Singapore, historically a major partner in trade and finance with Myanmar’s military and associated entities.

As per the report published by Andrews, last year documented that despite Singaporean government opposition to arms transfers to Myanmar, entities based in Singapore had become the military junta’s third-largest source of weapons materials, following Russia and China. There are many reports that there are companies linked to military junta working in Singapore. In 2022, the advocacy group Justice for Myanmar identified 38 Singapore-based companies involved in supplying weapons to the military, both pre and post the 2021 coup. Following a subsequent investigation by Singaporean authorities, Andrews reported in the document that the flow of weapons and related materials to Myanmar from Singapore-registered companies plummeted by nearly 90%, from $110 million to just $10 million. Total payments processed by Singaporean banks also declined sharply, from $260 million to approximately $40 million.

However, the decline in business with Singapore led to an increase in transactions with Thailand, where business shifted due to easier administration and a junta-friendly government. In Thailand, the numbers moved in the opposite direction to Singapore, with transfers of weapons and related materials from companies registered in Thailand doubling from over $60 million in 2022 to nearly $130 million last year. These transfers included the purchase of spare parts for Mi-17 and Mi-35 helicopters and K-8W light attack aircraft, which were previously sourced via Singapore-based entities and used to conduct airstrikes on civilian targets. Thai banks have been pivotal in facilitating this shift. For example, Siam Commercial Bank facilitated just over $5 million in transactions related to the Myanmar military in the fiscal year ending March 2023, but the figure jumped to more than $100 million the following year.

While the report demonstrates the junta’s ability to adapt to increasing financial restrictions, it also suggests that the campaign of Western sanctions is beginning to have an impact. Andrews notes that after the U.S. imposed sanctions on two state-owned banks last year, the Myanma Foreign Trade Bank (MFTB) and the Myanma Investment and Commercial Bank, the junta shifted most of its banking functions to Myanma Economic Bank (MEB), a state-owned bank that remains unsanctioned. Since then, MEB has processed tens of millions in payments for military procurement, receipt of international taxes and fees, and repatriation of foreign revenues from state-owned enterprises. Although Australia and Canada have also imposed sanctions on the first two banks, no foreign government has yet targeted MEB. The report emphasizes the need for the international community to shut down MEB’s international banking access through coordinated sanctions.

The people of Myanmar are in a dire situation, as the suppression of democracy and pro-democracy movements has led to a civil war. The military regime continues to receive business and arms support from various countries, including Russia, Singapore, and now primarily from Thailand, their neighboring country and biggest supporter. While some rebel groups have connections with Western governments, there are few reports of military aid from the West. With India and China, Myanmar’s large neighbors, showing little interest in intervening in the civil unrest, Thailand’s indirect involvement becomes a significant advantage for the regime, enabling it to prolong the war and maintain its military rule.