Tensions flared in headlines around the world as India carried out cross-border strikes into Pakistan — a retaliatory operation launched in response to the killing of a civilian tourist by Islamist militants in Pahalgam on April 22. Global media outlets have begun speculating about the possibility of a nuclear confrontation between the two long-time rivals.

Yet the events that unfolded around midnight on May 7 were far more calculated and limited in scope — though not without the potential to trigger broader consequences. The Indian government did not launch a war. Instead, it executed a targeted military operation focused specifically on the terrorist group Lashkar-e-Taiba and its affiliates, long-standing concerns for Indian security forces and the perpetrators of numerous attacks, including the 2008 Mumbai massacre and other recent cross-border strikes.

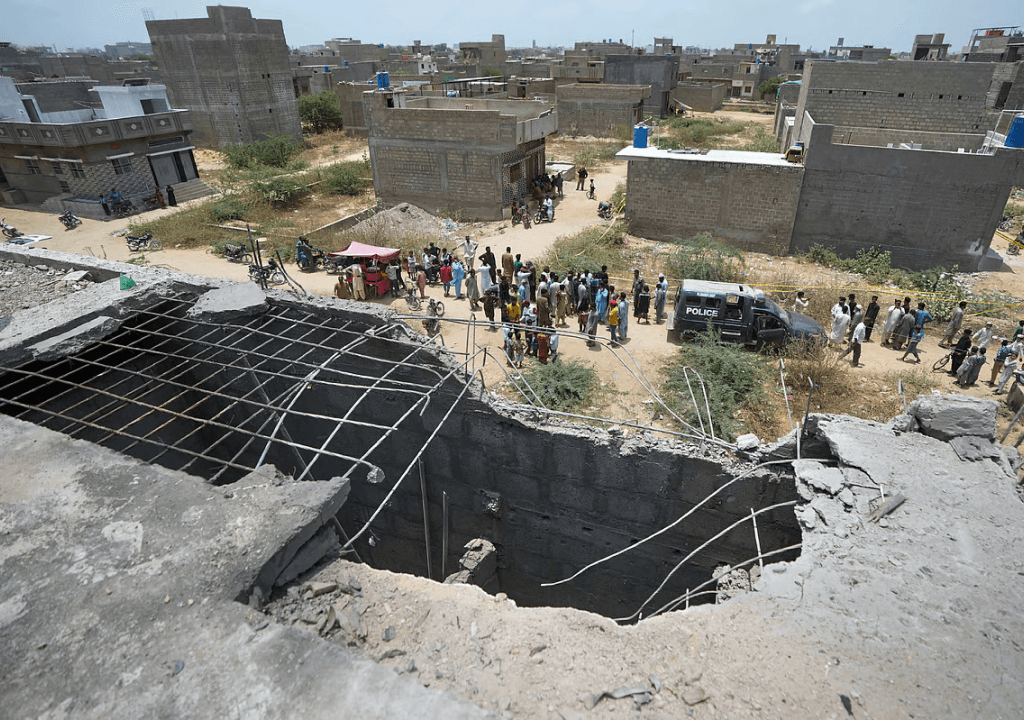

The Indian military reportedly struck buildings associated with these groups — many of them cloaked as Islamic religious institutions — while deliberately avoiding Pakistani military installations and civilian areas. This was not an assault on the Pakistani state, but a precise strike on a terrorist network that has operated with relative impunity under Islamabad’s watch.

Still, Pakistan has been publicly embarrassed — and it may yet feel compelled to respond.

What is Lashkar-e-Taiba?

Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT) is one of several Pakistan-based terrorist organizations engaged in the transnational export of Islamic extremism. Founded in 1986 as the militant wing of Markaz Dawat-ul-Irshad, a center for Islamic proselytization, LeT emerged during General Zia-ul-Haq’s Islamisation campaign, which aimed to reposition Pakistan as a nucleus of global political Islam.

The group is rooted in Salafism—a fundamentalist revivalist movement within Sunni Islam that originated in Saudi Arabia and receives substantial funding from various Islamist states. While LeT initially concentrated its efforts on waging jihad in Kashmir, it soon broadened its ambitions to include the ideological and territorial Islamization of India.

LeT drew global condemnation after orchestrating the 2008 Mumbai attacks, which killed 166 people, including foreign nationals. The organization espouses the establishment of a global Islamic caliphate and the recovery of territories it views as historically Islamic through both religious outreach and violent struggle. The UN Security Council has noted that LeT has conducted numerous terrorist attacks, including the Indian Parliament attack in 2001 and the 2006 Mumbai train bombings.

The group’s leader, Hafiz Muhammad Saeed, was arrested in Pakistan in 2019 and sentenced to 31 years in prison for financing terrorism. However, Pakistan has been widely criticized for staging his detention. Despite official claims, Saeed is reportedly being held in a military-protected compound equipped with private amenities, including a park, vehicles, a mosque, a madrasa, and additional security personnel. Even after his supposed incarceration, Saeed has consistently reaffirmed LeT’s ultimate goal: the fragmentation and eventual disintegration of India. The group’s ideology also harbors violent antisemitism, as evidenced by its targeted assault on a Jewish center during the 2008 Mumbai attacks.

Lashkar-e-Taiba’s connection with Pakistan

Lashkar-e-Taiba’s (LeT) ties with other Islamist groups and Pakistani institutions—particularly the military and the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI)—are deeply entrenched but deliberately obscured. While Pakistan historically supported armed Islamist groups as strategic proxies in Kashmir and Afghanistan, these relationships have become increasingly opaque in recent years.

In a 2012 essay for the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, security analyst Ashley Tellis noted that LeT was long favored by the Pakistani state because its objectives aligned closely with those of the military: asserting influence in Afghanistan and destabilizing India. The ISI maintained covert institutional links with LeT, offering financial support and combat training over a span of more than two decades.

Although LeT’s leader denied involvement in the 2008 Mumbai attacks, U.S.-Pakistani operative David Headley—who conducted reconnaissance for the operation—admitted coordinating with Pakistani intelligence. The exact level of official involvement remains unclear, but Pakistan’s unwillingness to fully dismantle LeT’s networks raises serious questions.

Despite Hafiz Saeed’s 2019 conviction for financing terrorism, he is reportedly held under relaxed conditions in a military-protected compound. Pakistan’s continued tolerance of LeT-affiliated entities, such as Jamaat-ud-Dawa (JuD), further undermines its claims of disassociation. JuD, presented as a charitable organization, is widely regarded as LeT’s front—an assessment echoed by the Australian government, the United States, and the United Nations.

Pakistan’s handling of Islamist militant groups resembles a franchise model. When a parent organization is banned, it often resurfaces under new names, maintaining the same ideology and leadership. Jaish-e-Mohammad (JeM), for instance, was founded by Masood Azhar after his release from Indian custody in 1999. Although banned in 2002 following the attack on India’s Parliament, JeM has persisted and maintained links with al-Qaeda and the Taliban, according to the UN Security Council.

What’s next?

Al-Qaeda has announced jihad against India in response to its operations targeting terrorists within Pakistan. As a result, India now faces threats on two fronts: one from the official Pakistani military, and the other from jihadist groups operating through religious justifications. While militants may infiltrate India to conduct terrorist activities, these groups also seek to radicalize and recruit Indian Muslims.

Radical Islamic scholars often frame the Islamization of India and the killing of non-believers as acts of religious virtue, a narrative that bolsters the appeal of terrorist groups like Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT). In Pakistan, such organizations are sometimes even held up as model entities by certain ideological factions. Their continued support within sections of society is fueled by the perception that Indian counterterrorism efforts are unjust, casting militants as martyrs and enhancing their recruitment potential.

Given this evolving threat landscape, India must prepare for increased terrorist activity—possibly exceeding the scale or immediacy of retaliation from Pakistan’s formal military. The security focus must expand beyond traditional state actors to include non-state militant networks capable of exploiting religious narratives and internal vulnerabilities.