Sangiin elections in Japan—the upper house of the National Diet—are usually quiet affairs, drawing less attention than lower house votes, as in many parliamentary systems. But this year was different. With public frustration mounting, the election became a revealing test of how voters are responding to economic pressure and an increasingly unpopular government. As expected, Shigeru Ishiba’s Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), already leading Japan’s first minority government since 1994, lost its majority in the Sangiin as well. While the outcome doesn’t immediately endanger the government, it marks a political shift—highlighting the decline of moderate conservatism, the rise of far-right forces, and growing opposition to Japan’s move toward a more open immigration policy.

Ishiba to Stay on

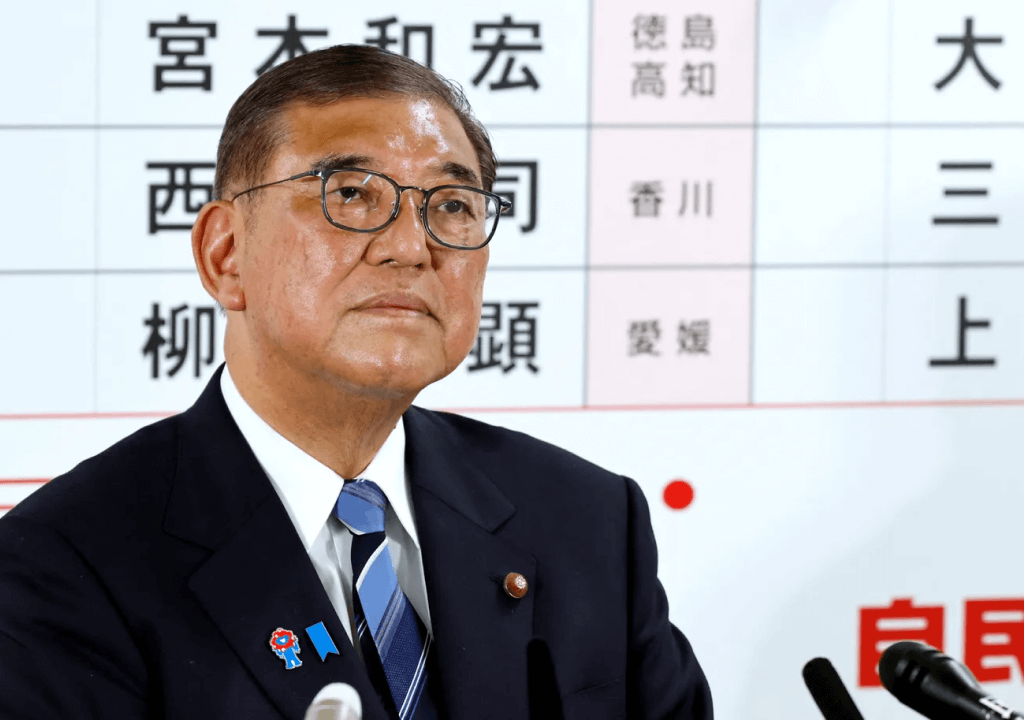

Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba, already weakened by the loss of the more powerful lower house in October and facing lukewarm support within his own Liberal Democratic Party, has pledged to stay in office despite his coalition’s failure to secure a majority in the upper house. Following the election, he acknowledged the severity of the outcome and made clear his intention to remain both as prime minister and party leader. At a subsequent press conference, Ishiba emphasized the need for continuity in government, pointing to the urgency of ongoing tariff negotiations and to fix the mounting strain of rising consumer prices on Japan’s economy.

To maintain a majority in the 248-seat Sangiin (upper house), the LDP and its coalition partner Komeito needed to win 50 seats in this election, where half the chamber was up for grabs. They fell short, securing just 47—39 for the LDP and 8 for Komeito—with one seat still undecided. While a few other conservative-leaning parties picked up seats, their willingness to support Ishiba’s government remains unclear. For now, any open alliance could prove politically costly, leaving Ishiba’s administration on increasingly precarious footing.

Mark Senseito’s Rise

Japan’s center-left Constitutional Democratic Party, the main opposition bloc, secured 22 seats in the recent election, raising its total in the Sangiin to 37. The center-right Democratic Party for the People, which offers conditional support to the ruling coalition, won 17 seats, bringing its total to 22. The Conservative Party of Japan also gained two seats, earning official party recognition.

However, it was the far-right Sanseito party that attracted the most attention. Known for its nationalist and anti-immigration platform—often compared to MAGA-style politics—Sanseito made a dramatic leap from one to 14 seats, becoming the third-largest vote-winner in the election. Now holding 15 seats in the 248-member upper house, the party has firmly established itself as a major emerging force.

Founded in 2020 through grassroots online activism, Sanseito promoted a nationalist agenda prioritizing Japanese interests and warning of an alleged creeping foreign influence. Its support has grown among voters disillusioned with mainstream parties—many of whom had long disengaged from electoral politics.

Political analysts are closely watching whether Sanseito’s rise signals a lasting shift in Japan’s political landscape, potentially mirroring the trajectory of other far-right movements such as Germany’s AfD or Reform UK.

After Effects

The election outcome has intensified pressure on the government to enact meaningful reforms. While the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) continues to champion fiscal restraint—aimed in part at calming jittery bond markets wary of Japan’s soaring public debt—this stance is increasingly misaligned with public sentiment. Recent polls show that a majority of households favor a cut in the consumption tax to ease inflationary strain, a proposal the LDP has resisted.

Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba may be allowed to remain in office for a few more weeks, at least until ongoing trade negotiations are finalized. The LDP is reluctant to initiate a leadership shake-up or call new elections, particularly with conservative votes splintering and the liberal Constitutional Democratic Party poised to benefit from any further disarray.

Even so, a change at the top could provide the LDP with a chance to reset its image, re-engage support from conservative allies such as the Democratic Party for the People and the Conservative Party of Japan, and better navigate the political polarization deepened by Sanseito’s surge. Though some observers believe that disenchanted conservative voters are gravitating more toward moderate alternatives like the DPP, Sanseito’s brand of populist nationalism may continue to resonate—especially among the sizable bloc of citizens who have long abstained from voting and now feel newly energized.