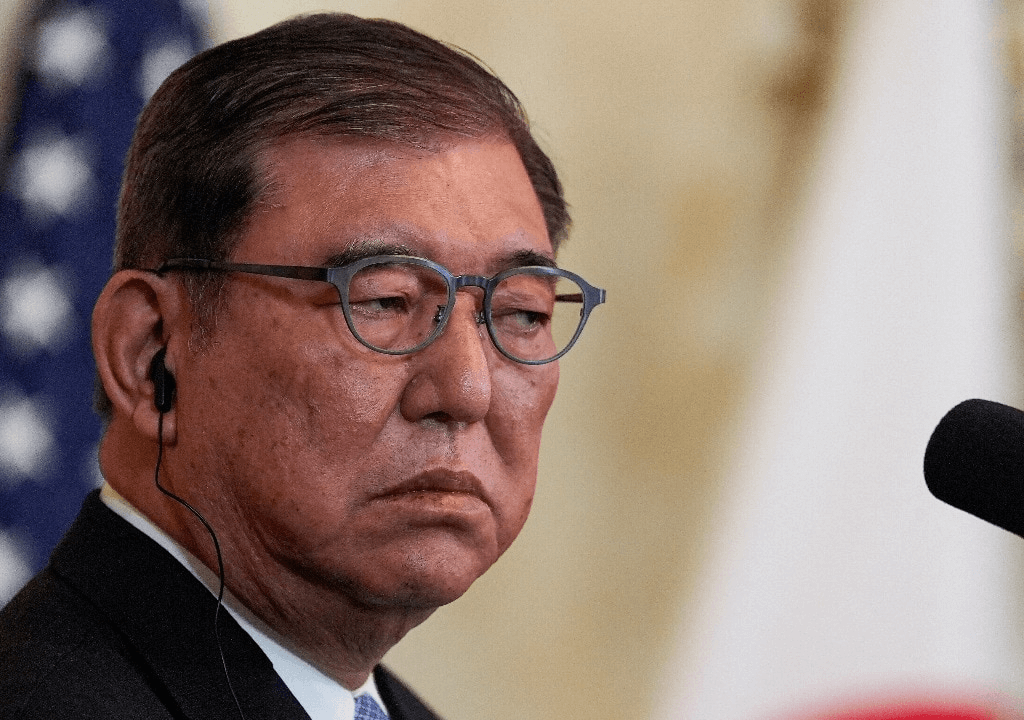

Shigeru Ishiba’s turbulent stint as prime minister ended in less than a year, adding to Japan’s political instability. He became the third consecutive leader to resign without completing his term.

Over his 362 days in office, Ishiba struggled with soaring rice prices threatening the nation’s staple food supply, the return of a tariff-driven Donald Trump disrupting trade, and a string of political missteps. Two election defeats further eroded his standing within the ruling party, making his resignation inevitable.

A Resignation to Save the Party

Shigeru Ishiba’s resignation had been anticipated any day after the heavy backlash in July’s upper house election, but he held on until September 7. The soft-spoken centrist, often described as both a reformist and a staunch Japanese nationalist aligned with the West, said he could no longer withstand the growing pressure inside his party.

Speaking to reporters on Sunday evening, just a day before rivals were poised to move against him, Ishiba said he was resigning to take responsibility for the election setbacks and to avoid a “decisive” split in the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP).

He had previously defended staying in office by pointing to ongoing trade negotiations with the United States. “Now that negotiations on US tariff measures have reached a conclusion, I believe this is the appropriate moment to resign,” he told reporters. “I have decided to step aside and make way for the next generation.”

Analysts said Ishiba’s resignation was aimed at preserving party unity. Reports suggested disaffected lawmakers were preparing to oust him by moving up the LDP leadership election, originally scheduled for 2027. Ishiba heightened tensions by resisting the plan and even threatening to call a snap general election. After talks with senior colleagues on Saturday, he admitted he could no longer lead the LDP, which as the largest party in the lower house holds the prime ministership.

The Election Gamble That Backfired

After winning both the LDP presidency and the prime ministership, Shigeru Ishiba called a snap election seeking a fresh public mandate and hoping to silence rivals on the party’s right. The gamble failed. Voters, furious at the party, used the election to register their disapproval in the wake of a major funding scandal. While most of the public anger was directed at the LDP as a whole rather than Ishiba personally, the scandal still damaged his image and weakened his leadership.

The fallout cost the LDP and its coalition partner Komeito their lower house majority, leaving Ishiba to govern with a fragile minority. His miscalculation that projecting freshness and campaigning vigorously would restore voter confidence proved to be a serious mistake.

In July’s upper house elections, the LDP lost its majority once again. This time, public anger was directed not only at the party but also at Ishiba himself, whose policies had deepened frustrations.

For the first time in postwar history, the Liberal Democratic Party, long the dominant force in Japanese politics, found itself without a majority in either chamber of parliament.

Public Anger Over Money in Politics Persists

The LDP may have retained power despite lacking a majority in both chambers of parliament. While voters did not seek to completely oust the party, the election results sent a clear message of dissatisfaction. If the party fails to understand and address this message, future prime ministers could face similar difficulties.

Former Prime Minister Fumio Kishida apologized in February for “Inviting suspicion and mistrust” after the funding scandal and promised to end fundraising parties. However, meaningful reforms were never implemented. Ishiba later offered his own apology after giving gift certificates, paid from his personal funds, to 15 newly elected LDP lawmakers. Critics argued that this gesture only reinforced the party’s entrenched culture of money politics.

As the Mainichi Shimbun, a leading Japanese newspaper, warned before the upper house election, lawmakers had greatly underestimated the intensity of public anger over political money.

Ishiba claimed progress by eliminating undisclosed “policy activity expenses,” but he and other LDP members resisted calls to ban corporate and group donations to party branches.

The fact that most politicians implicated in the scandal faced no indictments further fueled voter frustration. “There is no sign of self-reflection on the significant loss of trust in politics,” the Mainichi observed.

Ultimately, the same scandal that forced Kishida to resign also ended Ishiba’s premiership. Unless the party and government take meaningful steps to address the issue, the cycle is likely to repeat with the next leader.

Who Will Be Next?

The LDP is preparing to select its next leader, confident that a new figure can help the party recover. The upcoming leadership election in early October is seen as a chance to restore unity and stability. With Ishiba pledging not to run, attention now turns to potential contenders, and lawmakers and rank-and-file members are expected to cast their votes during the election.

Sanae Takaichi, the ultra-conservative former economic security minister who lost to Ishiba in last October’s leadership race, is likely to try again, with a chance to become Japan’s first female prime minister. Some analysts suggest the party may instead turn to agriculture minister Shinji Koizumi, son of former prime minister Junichiro Koizumi. Since his appointment in May, Koizumi has focused on curbing soaring rice prices. As environment minister, he once described addressing the climate crisis as “sexy” and “fun.”

The final outcome will hinge on the influence of senior lawmakers and other prominent figures who were close to the widely respected late prime minister Shinzo Abe, assassinated in July 2022.