While the world’s attention remains fixed on the Russia-Ukraine war—largely due to Europe’s involvement—and the Israel-Hamas conflict, which has deepened religious divisions, another war continues to unfold largely unnoticed. As global headlines focus on Gaza and Ukraine, Myanmar’s civil war rages on, drawing little international concern. For many, the country is little more than the backdrop of a viral meme featuring a dancing instructor oblivious to military tanks rolling past her during the 2021 coup. That coup dismantled Myanmar’s democratic government, plunging the nation into a relentless conflict between the military junta and various ethnic armed groups. Now in its fourth year, the war has inflicted widespread devastation, forcing mass displacement and causing staggering human losses. With no immediate resolution in sight, many believe the junta’s hold on power is weakening, raising the prospect of Myanmar fracturing along ethnic lines.

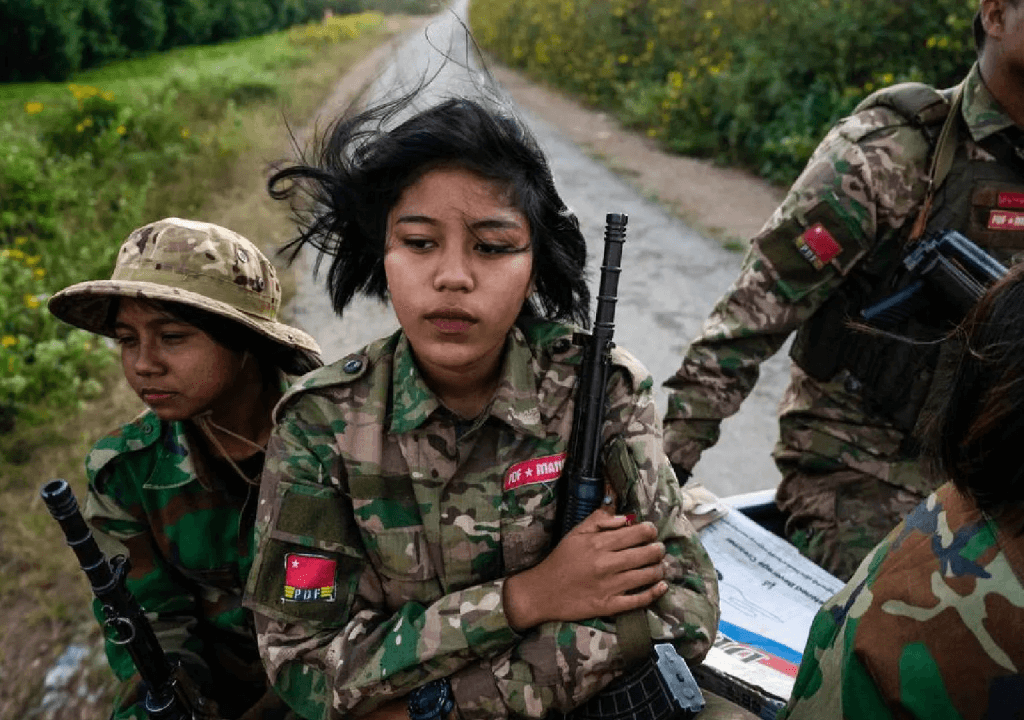

Four years into the conflict, resistance to Myanmar’s military junta has only intensified. A BBC study estimates that the regime now controls just 21% of the country’s territory, as it battles the People’s Defence Force—formed by the opposition National Unity Government, comprised of remnants of the National League for Democracy (NLD), which won Myanmar’s last democratic election—alongside long-standing ethnic armed groups resisting Naypyidaw’s rule.

Despite losing 95 towns, key trade routes, hundreds of military bases, and two regional commands, the junta still holds Myanmar’s major cities and central regions, making its removal far from imminent. Yet internal fractures are deepening, with growing calls for its leader, Min Aung Hlaing, to step down. In its desperation, the military continues to deploy brutal tactics—mass killings, torture, sexual violence, and relentless airstrikes on civilian areas. Any effort to further restrict its access to jet fuel should be pursued. The toll has been catastrophic: more than 4 million people displaced, half the population forced into poverty, and fewer than half with access to electricity. Rakhine State, one of the few places that occasionally draws international attention due to its Muslim population, is reported to have an especially dire crisis. The UN warns of imminent famine, with the Rohingya Muslim community particularly vulnerable—trapped between the military, which has forcibly conscripted men, and the Arakan Army, which accuses them of siding with the junta.

For many in Myanmar, military rule no longer feels like an inevitability. The junta’s refusal to compromise has convinced its opponents that a negotiated settlement is out of reach. Fears of post-junta chaos—and the potential toll on civilians—are understandable. Opposition groups have committed human rights abuses of their own and remain deeply divided, with often conflicting agendas. There is also concern about how a coalition government could function given these vast differences. However, despite these challenges, the opposition has managed to cooperate in surprising ways over the past four years.

The dramatic rebel advances of late October 2023 were made possible by China’s quiet backing of an alliance of ethnic armed groups, frustrated by the junta’s failure to curb cross-border criminal networks. But Beijing has since cut off arms supplies and key imports, now viewing the regime’s survival as its best chance to secure resources, maintain stability, and keep U.S. influence at bay. Notably, China has emerged as the strongest advocate for elections this year—an exercise that would be both a sham, given the 21,000 political prisoners in detention, and a logistical impossibility, as opposition forces have vowed to disrupt them.

Meanwhile, U.S. policy shifts are already having dire consequences. The Trump administration’s attacks on the National Endowment for Democracy threaten civic groups providing critical support to Myanmar’s population and would be essential in rebuilding the country. The freeze on USAID operations has already led to the withdrawal of medical care for 100,000 refugees in Thailand.

Beyond China and the US, other regional and global powers have a vested interest in Myanmar’s future. India, Thailand, and Europe are involved in varying degrees, with the West supporting the National Unity Government (NUG). However, the cooperation of ethnic armed groups in any future government remains uncertain. A federal union might be the best possible solution for Myanmar, but these groups, now deeply entrenched in their ethnic identities, govern their own territories like independent entities.

Take the Arakan Army, for example. It controls nearly all of Rakhine State, except for Sittwe, and operates autonomously, despite its nominal alliance with the NUG. If it were to receive support from other nations, it would likely push for full independence. The same applies to other ethnic groups, which, while currently united against the junta, could ultimately seek their own sovereignty.

As Myanmar marks the fourth anniversary of its civil war, it’s clear that a unified Myanmar, whether under military or civilian rule, is increasingly unrealistic. The coup and subsequent civil war have fractured the country. What remains is a power struggle among multiple factions, each vying for control.