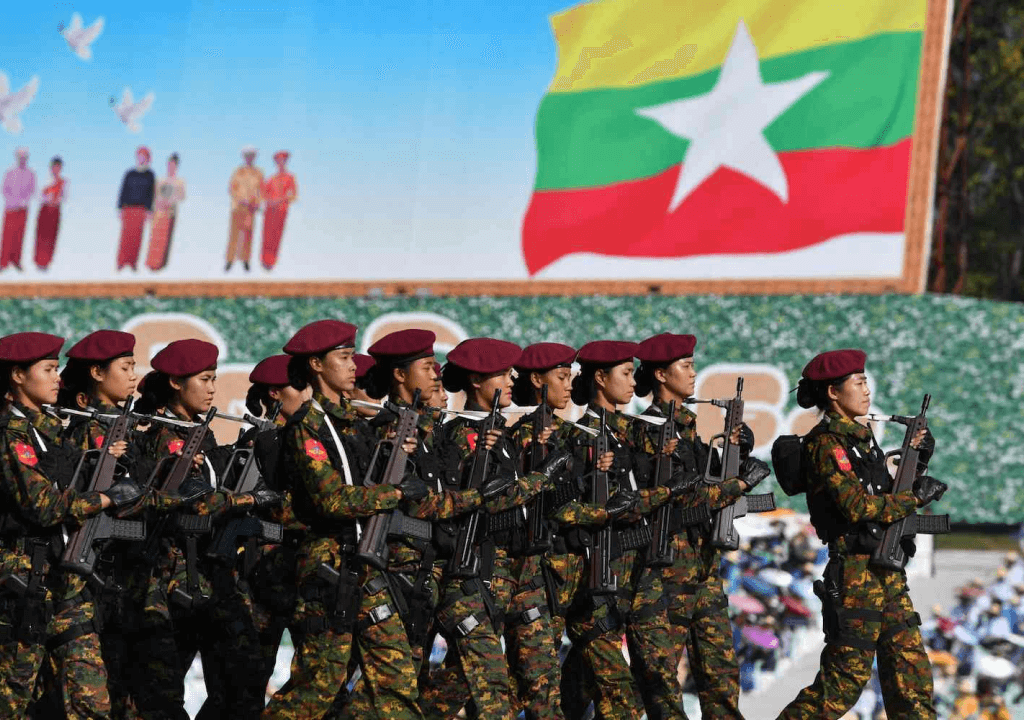

While the world’s attention fixated on the dramatic and much-publicized ceasefire between Israel and Hamas, a quieter but no less significant peace agreement took shape in Southeast Asia—largely unnoticed by the global media. Myanmar’s junta, which overthrew a democratically elected government in 2021 and plunged the country into an increasingly brutal civil war, reached a ceasefire with the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA), an ethnic rebel group from the country’s northeastern territories. China, with its strategic interests in maintaining ties to both parties, acted as mediator, and on January 18, the two sides finalized the agreement. This truce, forged in Kunming, a border city in southwestern China, represents a clear diplomatic victory for both Beijing and Myanmar’s military government. This is the second such truce mediated in Kunming within the past year, underscoring China’s growing role as a power broker in Myanmar’s tumultuous civil war.

The Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA), a rebel group composed of the ethnic Chinese Kokang minority, is a key player within Myanmar’s “Three Brotherhood Alliance” coalition. Founded in 1989, it was the first such group to enter into a ceasefire agreement with the Burmese government. This truce, which endured for nearly two decades, allowed the central government to formally recognize the Kokang region as “Shan State Special Region 1,” and ushered in a period of economic prosperity driven by illicit ventures. Opium cultivation and heroin production fueled both the MNDAA’s coffers and those of the Myanmar Armed Forces (Tatmadaw), as the region, strategically positioned near the Chinese border, became a nexus for illegal trade.

But in 2009, this fragile peace collapsed. Relations between the Kokang forces and the central government turned bitter, and the MNDAA was violently ousted, with many members fleeing into China. The region has been embroiled in a vicious cycle of conflict ever since, with the 2021 military coup igniting new waves of violence. As the civil war escalated, the MNDAA, along with various other rebel factions, banded together in a multi-front struggle against the junta, their armed resistance a symbol of defiance in the face of Myanmar’s fractured political landscape.

In January of last year, the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA) and the junta, under the watchful eye of Beijing, signed a ceasefire in Kunming, the capital of China’s southwestern Yunnan province. The pact, however, unraveled within six months, swallowed by the shifting tides of Myanmar’s entrenched conflicts. This year, China has stepped in again to broker another truce, and while skepticism abounds, observers suggest it might last longer. Beijing’s firmer intervention, combined with the junta’s increasingly precarious position, has made breaching the agreement a more onerous prospect. For now, China’s calculated pressure offers a flicker of hope for a temporary calm in a landscape dominated by turmoil.

China’s 2,000-kilometer border with Myanmar underscores its deep entanglement in the country’s political and military turmoil. Beijing maintains close ties with both the ruling junta and an array of rebel groups, including the Kachin Independence Army, which is advancing south against government forces, and the Three Brotherhood Alliance, which has seized military outposts and towns near the Chinese border since 2023. For China, the stakes of Myanmar’s conflict extend well beyond regional instability: the fighting imperils border security, disrupts trade routes, and threatens Beijing’s extensive infrastructure investments in the region.

Northern Myanmar, with its heavy reliance on China for communication infrastructure, energy initiatives, and financial support, risks severe economic disruption if the China-brokered ceasefire collapses. In a calculated move to reinforce stability, Beijing reopened all border crossings in MNDAA-controlled areas shortly after the truce was finalized. However, Myanmar’s value to China extends far beyond economic interdependence. Its strategic location provides Beijing with a crucial gateway to the Bay of Bengal and the Indian Ocean, offering an alternative route to the fraught waters of the South China Sea.

Beijing remains acutely attuned to the evolving dynamics in Myanmar, particularly the deepening ties between India and the Arakan Army, another influential rebel faction, and the growing Western support for the National Unity Government, the opposition to the junta. For China, stability in Myanmar is not a matter of altruism but necessity. A peaceful and fully democratic Myanmar may not align with Beijing’s strategic vision, but a measure of stability is essential to safeguarding its economic interests and geopolitical influence. For Beijing, peace is less about shared ideals and more about securing access, preserving influence, and safeguarding the uninterrupted pursuit of its regional ambitions—a hope it now pins on the success of the current ceasefire.