The 14th Singapore Parliament, which recently concluded, stands out as one of the most active and revealing legislative terms in the nation’s recent history.

Historically, Singapore Parliament has been characterized by brisk sessions, limited public debate, and minimal opposition involvement. This has led critics to describe the country’s political system as a “Managed Democracy,” where political plurality often appears more symbolic than substantial.

Yet, the 14th Parliament brought significant changes.

For the first time, Parliament formally recognized a Leader of the Opposition. Two opposition parties secured elected seats, introducing a rare level of political diversity into the proceedings. Debates became more dynamic and frequent, with some sessions stretching well past midnight.

The term also saw a surge in speeches, ministerial statements, motions, and adjournment debates—clear signs of a more participatory and engaged legislative process.

Whether these changes reflect a genuine political opening or a strategic adjustment by the PAP is still uncertain. Nevertheless, the 14th Singapore Parliament is likely to be remembered as a modest but meaningful turning point in the nation’s institutional development.

An active opposition

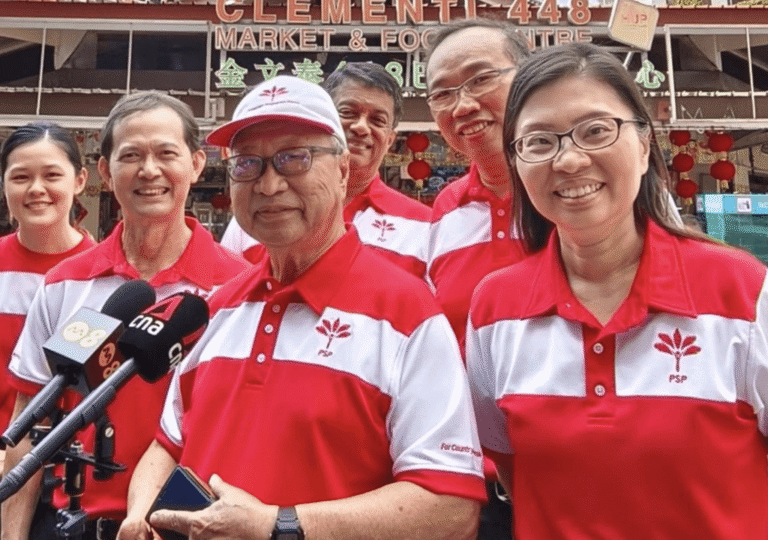

Once little more than a token presence, opposition lawmakers have become a more vocal and visible force, marking a significant shift in Singapore’s tightly controlled political landscape. Criticism of the country’s democratic deficit has long focused on the dominance of the ruling People’s Action Party (PAP), which held every seat in Parliament throughout the 1970s. Even in the 1980s, opposition representation never exceeded two elected members. That began to change with the 14th Parliament, which convened after the 2020 General Election. The Workers’ Party (WP), which secured 10 elected seats, led the charge, while the Progress Singapore Party (PSP) added to the opposition bench with two Non-Constituency Members of Parliament (NCMPs). Overall, the number of opposition lawmakers rose by 164 percent—a surge largely driven by the WP’s victory in Sengkang GRC, which brought four new members into Parliament.

Among all MPs, Louis Ng of the PAP stood out for his prolific activity. Representing Nee Soon GRC, he increased his parliamentary participation by 72 percent compared to the previous term. He submitted or clarified 728 parliamentary questions—more than double his earlier total—and delivered 195 speeches or clarifications on record. Others also made their mark. Yio Chu Kang MP Yip Hon Weng, WP’s Louis Chua, Jamus Lim, and He Ting Ru from Sengkang GRC, and PSP NCMP Leong Mun Wai were among the most active voices, shaping what has become one of the most engaged and diverse Parliaments in recent memory.

Both the WP and PSP have used their parliamentary platforms to challenge the government on key issues, ranging from economic inequality to housing. In response, the PAP has sought to reaffirm its relevance—not just as a ruling party, but as one willing to hold itself to account.

That effort has become increasingly visible online. The PAP has amplified its backbenchers’ contributions through social media, showcasing their questions and speeches. The message is subtle but clear: PAP lawmakers can scrutinize the executive just as effectively, making opposition voices—at least from the party’s perspective—less essential.

More motions in Parliament

Parliament became noticeably livelier during the 14th term, with many sessions stretching late into the night. Nearly one-third of sittings extended past 8 p.m., up from 18 percent in the previous term. Notably, nine sessions went beyond 10 p.m., compared to just one in the prior term—when Parliament passed the controversial Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Bill.

Five of those nine late-night sittings stemmed from motions led by the opposition. These included the Progress Singapore Party’s (PSP) debates on public housing (February 2023) and foreign talent (September 2021), both of which drew counter-motions from government ministers and triggered lengthy discussions. Other extended debates were driven by Workers’ Party (WP) motions on justice reform and the cost of living, and a PSP motion on hawker support—often amended by PAP MPs before being passed.

The 14th Parliament also set a new record with 20 private member’s motions, more than doubling the nine introduced in the previous term and surpassing the previous high of 18 during the ninth term. This increase highlights the opposition’s growing understanding of how private motions can shape the legislative agenda and steer public debate.

Opposition MPs have used these motions not just to propose alternative policies but to directly challenge the PAP’s long-standing dominance. WP MPs submitted four motions, including on sports and cost-of-living concerns. The PSP’s two NCMPs filed eight, covering topics like the abolition of group representation constituencies and the call for a neutral Speaker of Parliament. PAP MPs contributed seven motions addressing issues such as climate change, mental health, and digital inclusion. Three Nominated MPs jointly filed one motion on healthcare support.

More engagement with Public

The increase in the number of motions tabled in Parliament is a welcome development, as it elevates policy debates into the public domain with greater visibility and institutional significance. The 14th Parliament recorded an unprecedented 59 ministerial statements—more than double the 29 issued in the previous term. These statements function as a strategic tool for the Government to communicate its key messages, foster informed debate, and build both parliamentary and public consensus on complex policy matters.

By formally placing its positions on record through ministerial statements, the Government not only sets the policy agenda but also demonstrates a willingness to engage substantively on issues of public concern. This reflects a shift toward deeper, more structured parliamentary engagement.

Addressing issues through ministerial statements, rather than within the time-limited 90-minute question window, is also a pragmatic choice. It allows ministers to articulate their positions in greater detail without crowding out other questions scheduled for oral reply. While standard Q&A formats remain an option, ministerial statements provide a more comprehensive and coherent platform for communicating policy and intent.

Last Parliament, Future Politics?

The 14th Parliament marked a pivotal moment in Singapore’s political evolution. It saw a historic rise in opposition representation and an unprecedented number of motions initiated by non-ruling parties. The introduction of live telecasts transformed parliamentary proceedings into a national spectacle, offering the public an unfiltered view of debates and decision-making.

This heightened visibility served both sides of the aisle. While the opposition leveraged the platform to highlight alternative perspectives, the ruling People’s Action Party (PAP) used the same medium to underscore its continued leadership and responsiveness. Yet with greater transparency came increased public scrutiny—parliamentary performances were more closely watched, dissected, and debated than ever before.

For many Singaporeans, the 14th Parliament dismantled long-held perceptions of Parliament as the exclusive arena of the PAP. It demonstrated that opposition members could make substantive contributions to national discourse, offering credible alternatives rather than symbolic dissent.

This shift is likely to ripple into future elections. Voters who once felt politically disengaged may now be more inclined to support alternative voices, ushering in a more competitive and pluralistic political landscape. Over time, these developments could help deepen democratic norms and move Singapore closer to becoming a fully mature and inclusive republic.