PAP proved they own Singapore. After more than six decades of uninterrupted rule since 1965, the 19th Singapore General Election, held on May 3rd, felt markedly different. For the first time in years, there was a sense of real competition. The ruling party faced a host of challenges: a decline in vote share, a growing number of opposition seats, the rise of identity politics, and increasing public discontent over the cost of living. Adding to the pressure was a leadership transition—Singapore’s first Prime Minister not from the Lee family—and mounting support for the opposition from foreign media.

Yet, despite mounting challenges, voters renewed their trust in the PAP, entrusting leadership to Prime Minister Lawrence Wong. Knowing that even a slight drop in support could be turned against him, Wong ran a tightly controlled, strategically calculated campaign. Five years earlier, the PAP cast itself as the steady hand guiding Singapore through the COVID-19 crisis. This time, the story was the same, but the threat had changed—global trade instability, fueled in part by President Trump’s policies. Once again, the message landed—and the strategy delivered.

The expected result, but not yet to this extent.

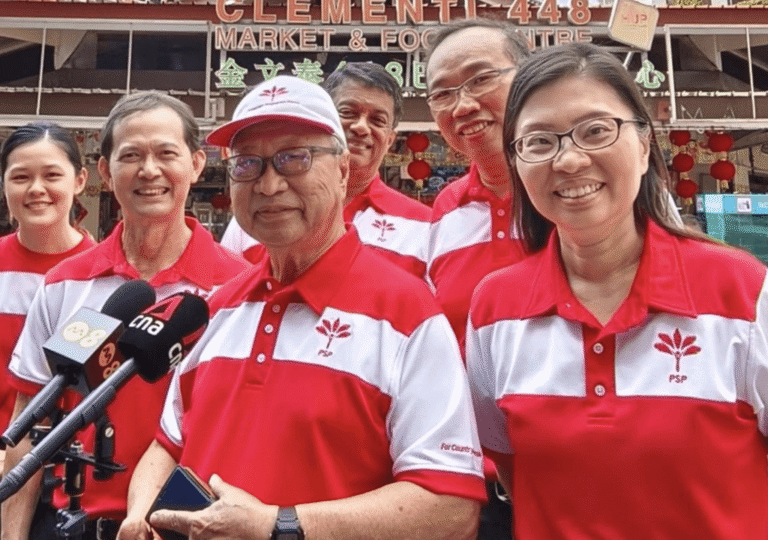

Everyone anticipated the result before the election, but the winning margin and the backlash faced by the opposition were unexpected. The PAP secured 87 out of 97 seats in the unicameral Parliament, with its share of the popular vote rising to 65.6 percent, up from 61.2 percent in the 2020 election. Despite repeatedly calling for increased opposition representation in Parliament, the opposition struggled to gain ground. Among the 11 opposition parties, including two independent candidates, only the Workers Party won seats, sending 10 representatives to Parliament—maintaining the same number as in 2020, although their vote share increased by 14.99 percent. Red Dot United, which fielded more candidates after the two major parties, failed to win any of its 15 contested seats but saw a 3 percent increase in votes. All other parties, including the PSP, experienced significant declines in support. PSP, which had secured two seats in the last Parliament, failed to win any this time, while the rest of the parties also faced disappointing results.

Full Result: https://www.eld.gov.sg/finalresults2025.html

All positives for the PAP.

The People’s Action Party (PAP) delivered a decisive victory after a near record-low performance in 2020. While it was clear the party would retain power, this year’s election was seen as a critical test of both its popularity and the appeal of its new leadership. Voters responded to the PAP’s call for stability, rallying behind the party’s message amid the ongoing trade war and tariff issues, expressing a desire to avoid taking any risks with their votes.

The election outcome served as a clear endorsement of Prime Minister Lawrence Wong, who had argued that the PAP was best suited to navigate the ongoing trade war and tensions between the U.S. and China. Wong had warned that U.S. tariffs would negatively impact Singapore, a small nation of nearly six million people, one of the wealthiest in the world on a per capita basis.

For Wong, the election was a personal victory. He expressed that the results showed Singaporeans understood the message he had sought to convey. However, he also acknowledged that many Singaporeans still wanted more opposition members in Parliament, a view he respected. He confirmed that the Workers Party would be granted two additional seats, bringing its total representation to 12 in Parliament. This move presented him as a leader who values democracy and is committed to inclusivity.

A blow for the WP.

During the campaign, Workers Party rallies attracted large crowds, reflecting a public appetite for more robust debates in Parliament and a wider range of voices in national policymaking. Many had anticipated that the People’s Action Party’s (PAP) dominance might erode, particularly as growing numbers of Singaporeans expressed frustration over economic stagnation. The rising cost of living and the challenges of daily life, compounded by increasing sales taxes and declining housing affordability, were central issues highlighted by the opposition.

Despite these concerns, many voters remained hesitant to fully trust the Workers Party. External uncertainties—such as geopolitical tensions and economic volatility—appeared to have a stabilizing effect on voter sentiment, reinforcing appreciation for a government perceived as competent and steady, even amid domestic discontent.

Furthermore, allegations against the Workers Party concerning racial politics and a perceived lack of coordination among opposition parties contributed to its disappointing performance. These factors, along with the public’s preference for stability, ultimately worked in the PAP’s favor. Other opposition parties were largely sidelined, as this election was widely framed as a direct heavyweight contest between the PAP and the Workers Party

Criticism may persist.

While Singapore’s election delivered a decisive mandate to the People’s Action Party (PAP) and a disappointing result for the opposition, several Western media outlets have raised concerns about the nature of the mandate. Even though numerous factors clearly worked in the PAP’s favor, and there were no major disputes over electoral integrity—yet the scale of the PAP’s victory still surprised some international observers.

Opposition parties criticized the PAP for holding one of the world’s shortest campaign periods—just nine days—and for allegedly redrawing electoral boundaries in districts where the opposition had previously gained support. The PAP dismissed these accusations, asserting that the committee responsible for reviewing electoral boundaries operates independently of the government. In the end, voters appeared to prioritize stability, reaffirming their trust in the PAP—even as international media continue to question the fairness of the process.