Singapore may move its general election forward from November to as early as May, prompting officials to finalize new constituency boundaries in early March. This election is expected to be one of the most significant in recent decades, as Prime Minister Lawrence Wong—Singapore’s first leader from outside the Lee family—seeks his own mandate. With the ruling People’s Action Party (PAP) holding a supermajority since independence, the upcoming polls will serve as a key test of Wong’s leadership.

The redistricting has reshaped several key battlegrounds from the 2020 election ahead of the 2025 General Election (GE). While officials attribute these adjustments to demographic shifts, the changes have sparked debate over their political impact. Several battlegrounds from GE2020—where the Workers’ Party (WP), Progress Singapore Party (PSP), and Singapore Democratic Party (SDP) mounted strong challenges—have been significantly redrawn.

The Politics of Demarcation

Significant population shifts in certain regions have undoubtedly influenced recent boundary changes, but for some voters, the redistricting still appears politically motivated. For the first time in decades, the committee has attempted to justify its decisions—an effort observers view as a step toward greater transparency. However, skepticism remains.

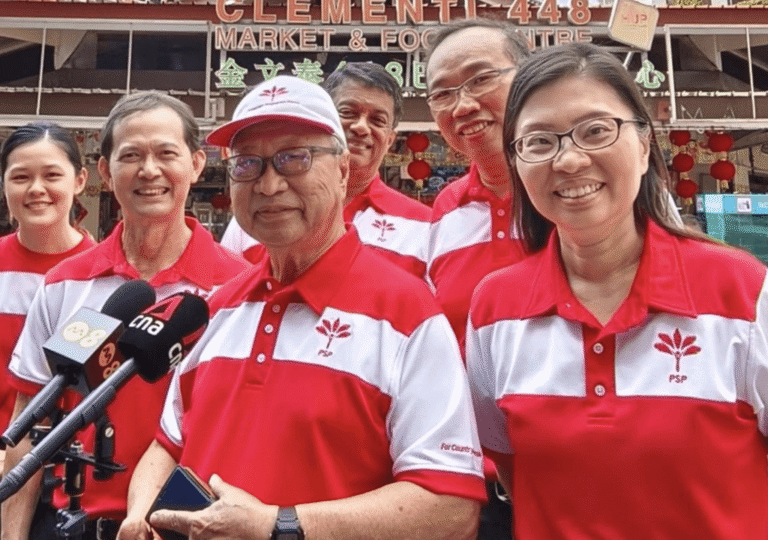

Several constituencies previously contested by opposition parties like the PSP and SDP have either been eliminated or absorbed into other wards, forcing these parties to rethink their strategies. Despite having spent years building voter support, they now face the challenge of adapting to a reshaped political landscape. An early election could further diminish their remaining opportunities.

While officials attribute these adjustments to rapid population growth in adjacent constituencies, critics argue that the changes disproportionately disadvantage opposition parties. Nevertheless, the WP, PSP, and SDP have all signaled their intent to contest these areas again in the upcoming election.

In Singapore’s tightly controlled political environment, opposition parties have historically been cautious in challenging the ruling People’s Action Party (PAP), often operating within the constraints of a system that overwhelmingly favors the incumbent.

New Wards, New Fights

There are only a few wards in Singapore where opposition parties can realistically hope to secure parliamentary representation, and this remains the case even after the latest redrawing of electoral boundaries. One of the most closely watched new wards, Jalan Kayu SMC, has already attracted interest from the People’s Alliance for Reform, the People’s Power Party, and Red Dot United.

Singapore’s western region has undergone significant boundary changes, many of which are seen as weakening opposition prospects. These include the creation of a new West Coast-Jurong West GRC, which absorbs parts of the existing Jurong GRC while transferring Dover and Telok Blangah to Tanjong Pagar GRC. Additionally, Jurong GRC has been reconfigured into the newly established Jurong East-Bukit Batok GRC, Jurong Central SMC, and portions merged into Holland-Bukit Timah GRC.

One of the most consequential changes for the opposition is the formation of Jurong East-Bukit Batok GRC, which absorbs Bukit Batok SMC. This shift could be a setback for SDP chief Chee Soon Juan, who secured 45.2 percent of the vote in Bukit Batok in 2020 and had announced his intention to contest the ward again.

While the west has seen major changes, boundary adjustments in the east could also reshape electoral dynamics. The creation of Punggol GRC from the existing Pasir Ris-Punggol GRC poses little challenge for the ruling party.

An Earlier Election?

The release of the EBRC report on March 11 has intensified speculation about a possible May election, with many observers noting that the timeline aligns with past electoral patterns. Since 2006, general elections—except for GE2020—have typically been held about two months after the EBRC report’s release, making May a plausible timeframe.

The redistricting has further complicated the opposition’s position, and the administration may be disinclined to give them additional time to adapt their strategies.

As Singapore’s longest-serving Parliament, the 14th Parliament could hold its final sitting in the first week of April before dissolution. This would leave roughly eight weeks between the EBRC report’s release and a potential Polling Day in early May.