While Singapore projects a modern and open image, its political system is often viewed—especially in the West—as disproportionately favoring the ruling party. More than six decades after independence, the nation’s electorate continues to show little inclination toward political change. In the 2025 general election, the ruling party once again secured a resounding landslide victory. Despite repeated calls for broader political representation, there remains a deep-rooted reluctance to support the opposition or consider alternative parties. To outsiders, such unwavering loyalty might raise eyebrows. Yet, despite accusations of gerrymandering and critiques from Western media, public trust in the electoral process within Singapore remains largely intact. Why then, after years of stability and prosperity, do Singaporeans remain hesitant to embrace political alternatives?

A Devastating Blow to the Opposition

No one—literally no one—expected a change in leadership this time. Anyone familiar with Singaporean politics would not have seriously considered it. Yet, there were signs that the opposition had a fighting chance: a new leader emerged outside the Lee family legacy, rising living costs stirred discontent, and the opposition had proven itself competent in the last parliament. Still, voters hesitated to support alternative parties. Instead, a wave of support carried the ruling party to another sweeping victory. There was no anti-incumbency to speak of, and for the opposition, the outcome brought surprise, frustration, and deep disappointment.

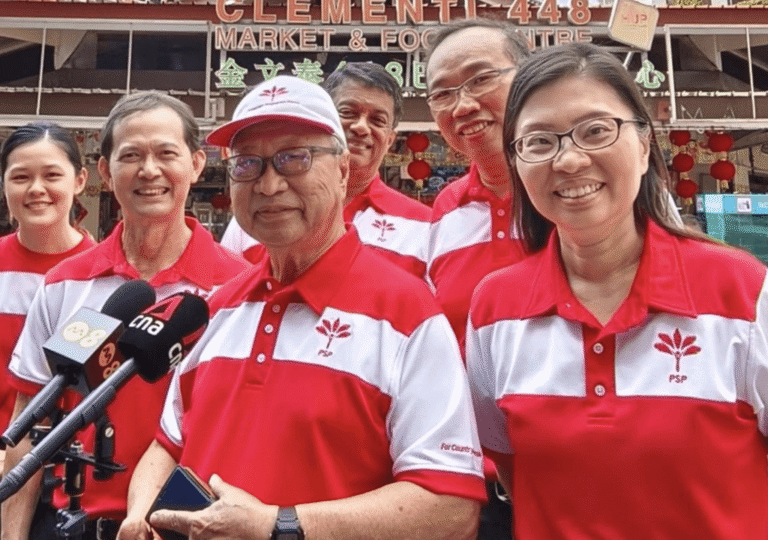

The Workers’ Party, despite a strong campaign, failed to make major gains. While they did improve their overall vote share by 3.77%, they merely returned to their previous number of seats and added two non-constituency MPs—an achievement, but far from a breakthrough. Meanwhile, the Progress Singapore Party (PSP), once considered a rising force after a strong performance in the previous election, suffered a major setback. They lost all representation and saw a significant drop in support.

Smaller opposition parties fared even worse. A total of 27 candidates from the National Solidarity Party (NSP), People’s Alliance for Reform (PAR), People’s Power Party (PPP), and Singapore United Party failed to gain traction, all polling below 12.5% and collectively forfeiting $364,500 in election deposits—the highest ever lost in a Singaporean election.

Why don’t people even consider the opposition?

Hundreds of analyses have emerged online, each offering a take on the outcome of Singapore’s recent election. Yet most converge on a single conclusion: voters overwhelmingly rejected the smaller “mosquito parties”—a dismissive term for groups with disjointed candidate lineups, weak grassroots networks, and vague policy agendas. For many, these parties didn’t even register as viable options. This wasn’t merely a loss; it was a resounding repudiation. The electorate delivered a clear message—hesitation, if not outright refusal, to entrust these parties with meaningful political responsibility.

Even though many of them addressed pressing issues such as the cost of living, housing, and healthcare, their campaigns failed to resonate. This raises an enduring question: do Singaporeans truly want political change?

Perhaps the most straightforward answer is that the status quo feels safe. The People’s Action Party (PAP) has become woven into the national psyche—synonymous with progress, stability, and governance. For many, supporting the PAP feels less like a choice than a civic norm. Especially in a volatile global economy, voters appear to favor continuity over risk.

Yet a desire for limited opposition persists. Voters seem to support the idea of checks and balances, but within clearly defined limits. Surveys by the Institute of Policy Studies, conducted after every general election since 2006, consistently reveal a public interest in greater political diversity. Still, the 2025 results suggest Singaporeans prefer that change to come gradually—measured and managed, rather than sudden or sweeping.

Evolving Politics in Singapore

The People’s Action Party (PAP) has long cultivated the image of being inseparable from Singapore’s national success—championing economic growth, racial harmony, and political stability. In this election, that narrative once again took center stage, skillfully reinforced by Lawrence Wong, who positioned the PAP as the indispensable steward of the nation’s future. The result was a commanding victory that reaffirmed the party’s dominance.

Meanwhile, the Workers’ Party (WP) solidified its role as the country’s credible opposition. Although it didn’t significantly expand its parliamentary presence, it retained public trust and institutional standing—further marginalizing smaller parties. For many voters, the political landscape appears to have crystallized—and perhaps for good: the PAP governs, the WP provides oversight, and the rest are pushed to the margins. Singaporeans are shaping a distinct kind of political balance.