As South Korea’s presidential election draws near, the three main candidates are ramping up their campaigns in an increasingly competitive race. Democratic Party candidate Lee Jae-myung holds a lead, while People Power Party contender Kim Moon-soo is making a final push to close the gap. Meanwhile, Lee Jun-seok of the New Reform Party is gaining traction, recently hitting double-digit support in the polls.

With early voting set to begin on Thursday, candidates are making their final strategic moves. Lee Jae-myung is adopting a more centrist tone to widen his appeal, while Kim is working to unify the conservative vote by seeking an alliance with Lee Jun-seok—a former PPP leader now running under his own party’s banner.

A Realmeter poll released on Saturday shows Lee Jae-myung leading with 46.6 percent support, followed by Kim at 37.6 percent, and Lee Jun-seok at 10.4 percent. Under election law, no new opinion polls can be published starting Wednesday, making this week’s results the final glimpse of public sentiment before election day.

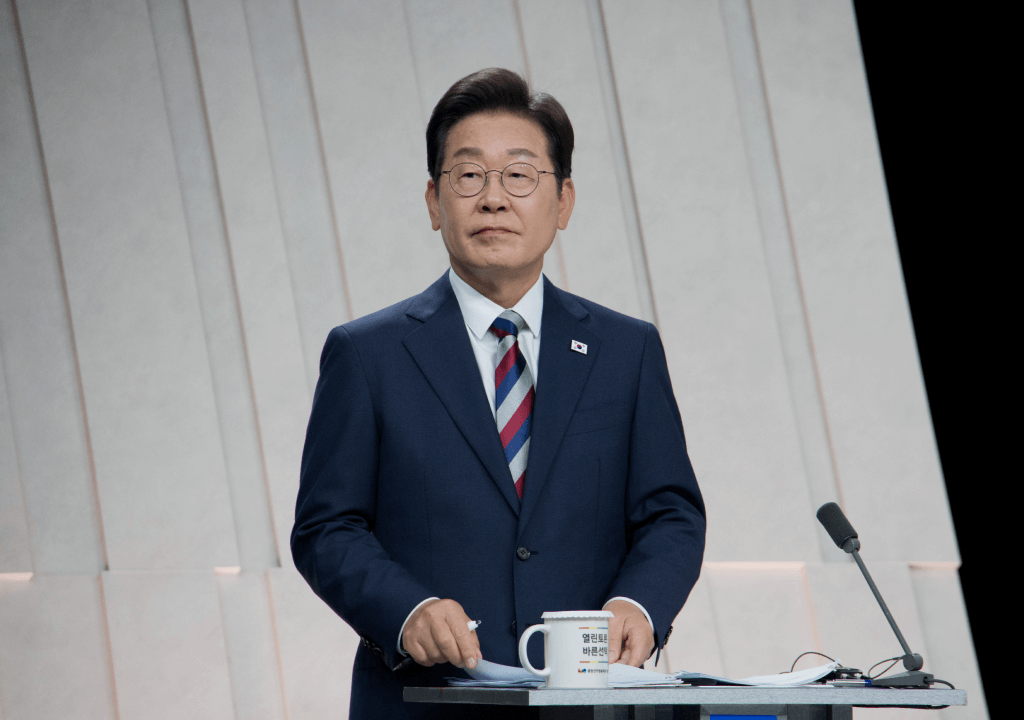

Lee Jae-myung to Court Centrist Votes

Left-liberal candidate Lee Jae-myung is reaching out to centrist voters in an effort to consolidate his lead. At 60, Lee narrowly lost the 2022 presidential race to Yoon Suk-yeol, but retained a parliamentary majority that he used to obstruct much of Yoon’s policy agenda. He later led the impeachment drive that removed Yoon from office after the controversial martial law declaration.

Lee has pledged to introduce a supplementary budget to stimulate the economy and proposed forming a task force under his leadership to tackle the country’s slowing growth. In response to conservative criticism labeling him “Pro-China and anti-American,” Lee has reaffirmed South Korea’s commitment to its alliance with the United States and voiced support for trilateral cooperation with Washington and Tokyo—while remaining open to dialogue with North Korea.

He has also dismissed speculation of a conservative coalition ahead of the election, describing it as an attempt to unite what he termed “insurrection forces.”

Kim Aims to Consolidate Conservative Votes

Kim Moon-soo clinched the People Power Party’s nomination with strong support from conservative voters, bolstered by his initial refusal to apologize for former President Yoon Suk-yeol’s martial law declaration—though he later issued a formal apology for the unrest it caused. A former labor minister under Yoon, Kim has embraced his predecessor’s brand of hyper-nationalism and staunch opposition to the left. He has pledged to revive the economy by backing key industries and frequently cites his success in bringing Samsung Electronics’ semiconductor plant to Pyeongtaek during his time as governor of Gyeonggi Province.

On defense, Kim has proposed building nuclear-powered submarines to strengthen South Korea’s deterrence against North Korea. He has also worked to shift public focus to Lee Jae-myung’s legal troubles, highlighting the Democratic Party candidate’s ongoing corruption trials and accusing the party of advancing legislation intended to shield him from prosecution.

Kim has warned that a Lee victory could result in unchecked power across the executive, legislative, and judicial branches—raising the prospect, he argues, of authoritarian-style governance.

Lee Jun-seok to Split Conservative Vote

Lee Jun-seok, a 40-year-old conservative and outspoken anti-feminist, is the youngest candidate in the race and a vocal supporter of former President Yoon Suk-yeol’s impeachment. Despite growing pressure from the People Power Party, which has thrown its support behind Kim Moon-soo, Lee has vowed to remain in the race until the end.

Once the youngest-ever chair of the People Power Party, the Harvard-educated Lee now represents the breakaway Reform Party, which he founded. Polling in third place, he has emerged as an unexpected disruptor within the conservative camp.

Lee has sharply criticized his former party for failing to distance itself from the disgraced Yoon. Yet, paradoxically, his own positions often lean even further to the right.

Campaigns are in their final hours.

Fears that South Korea’s presidential election would spiral into toxic polarization—following the political upheaval sparked by Yoon Suk-yeol’s martial law declaration—have not materialized. Despite the turmoil, the national mood has gradually shifted back to core concerns such as the struggling economy and the decline of key industries.

With the Democratic Party of Korea (DPK) on track to capture the presidency, the liberal bloc may soon control both the executive and legislative branches. Such alignment could pave the way for the kind of coordinated policymaking that has long eluded Seoul. Meanwhile, the conservative camp remains fractured, and all eyes are on how the breakaway Reform Party will perform at the polls.

The election is set for June 3, and a winner is likely to be declared by early the following day. The new president will assume office immediately—without the benefit of a formal transition from the outgoing administration