Long wary of being seen as a satellite of India, Sri Lanka has spent decades navigating its foreign alignments—at times courting the West, and more recently, leaning heavily toward China. That pivot, especially during the Rajapaksa era, brought a surge of Chinese investment but also coincided with one of the most severe economic crises in the island’s post-independence history. Now, under the weight of that collapse, Sri Lanka appears to be rebalancing. The island nation is quietly edging back toward New Delhi—not through grand gestures, but via a deliberate flow of strategic agreements and behind-the-scenes diplomacy.

For Colombo, this shift marks a pragmatic recalibration. What was once seen as a one-sided relationship with India is increasingly viewed as a possible path out of economic despair. For New Delhi, the moment offers both a strategic opening and a pressing imperative. By providing critical aid, essential supplies, and infrastructure investment, India is not only helping to stabilize its southern neighbor but also reinforcing its presence in a region where Beijing’s influence has grown markedly.

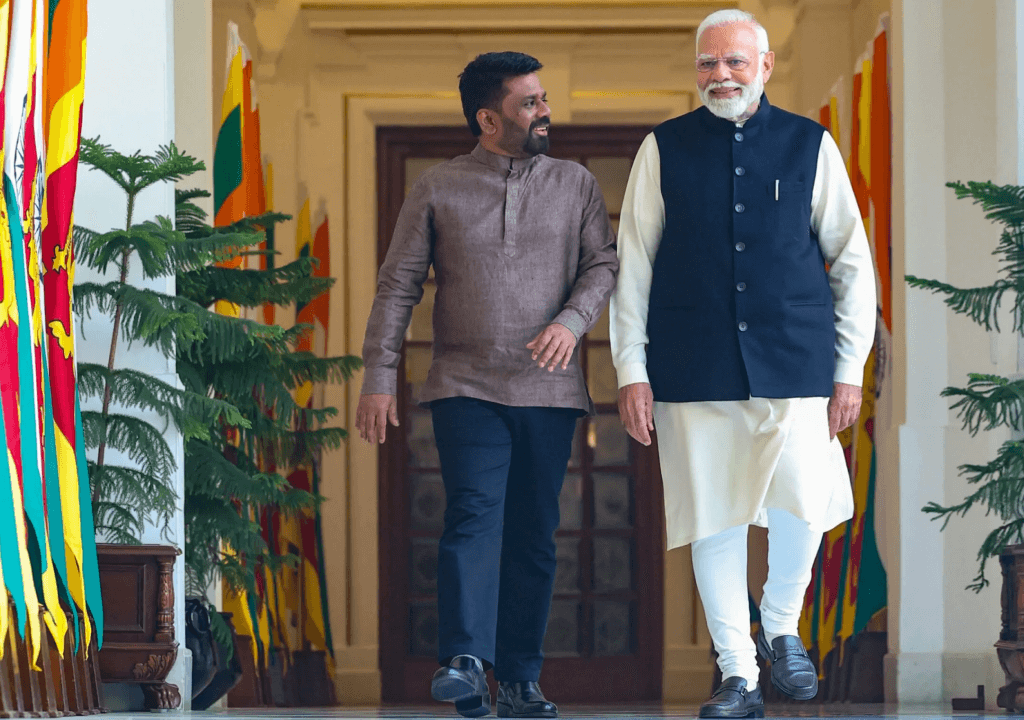

Modi’s visit to Sri Lanka

Narendra Modi, the Indian Prime Minister who has skillfully crafted diplomatic relationships across the region, recently made a significant visit to Colombo. The trip—his first to Sri Lanka since President Anura Kumara Dissanayake took office in September last year—served as a symbol of the changing dynamics in South Asian geopolitics.

During the visit, India and Sri Lanka signed seven key agreements spanning defense, energy, digital infrastructure, health, and trade. The move signaled a recalibration in regional alliances, as both nations work to counterbalance China’s growing influence in the Indian Ocean.

Initially, concerns in New Delhi centered around Dissanayake’s leftist background and potential leanings toward Beijing. However, those apprehensions have since softened. Instead of drifting closer to China, Colombo appears to be re-engaging with New Delhi in a more pragmatic and strategic manner.

Dissanayake reassured Modi that Sri Lanka would not permit its territory to be used in any way that might threaten India’s security. Modi, in turn, welcomed the gesture, emphasizing the deeply interconnected nature of security interests between the two nations.

India Backs Sri Lanka’s Core Needs

Amid an economic collapse and mounting debt to China, India provided vital supplies and assistance when Sri Lankans needed them most. While China invested heavily in large-scale infrastructure projects—many of which offered limited benefits to ordinary citizens—India’s approach focused on immediate relief and practical support. This made a lasting impact on the public and nudged the Sri Lankan government toward rebuilding trust and strengthening ties with New Delhi.

That relationship is now evolving. Expanding beyond emergency aid, India is investing across multiple sectors. As a symbol of this growing partnership, the two leaders recently inaugurated—virtually—the construction of a 120-megawatt solar power plant, a joint venture funded by India and aimed at advancing Sri Lanka’s energy future.

Sri Lanka needs to balance

While Sri Lanka is working to repair its relationship with India, cutting ties with China is far from simple. China remains Sri Lanka’s largest bilateral creditor, accounting for over half of the island’s $14 billion in bilateral debt at the time of its sovereign default in 2022. The economic collapse, however, forced Colombo to rethink its heavy dependence on China—a reliance that had contributed to the crisis—and created space for India to step in with substantial financial and material assistance.

Nonetheless, China’s role in restructuring Sri Lanka’s infrastructure loans remains vital. President Dissanayake’s first official overseas visit to New Delhi in December signaled a renewed diplomatic warmth, but his subsequent trip to Beijing in January underscored the balancing act Colombo must maintain. That same month, Sri Lanka signed a $3.7 billion investment deal with a Chinese state-owned company to build an oil refinery in the country’s south, reaffirming Beijing’s enduring economic footprint.

It’s evident that Sri Lanka still looks to China for large-scale funding—support that India, thus far, has been cautious to extend. As such, it would be premature to declare a pro-India tilt in Colombo’s foreign policy. Instead, Sri Lanka appears to be navigating a delicate path, seeking to balance both powers in pursuit of its own national interests.

What happens next?

It’s clear that Trump’s trade policies have shaken the global order. China is no longer the China the world once knew; it is now seeking broader relationships rather than maintaining a confrontational posture. This shift will inevitably influence dynamics in South Asia as well. The region, with its massive population, represents a significant market that China cannot afford to ignore. Yet among South Asian nations, India stands out with the strongest purchasing power—making a stable relationship with New Delhi increasingly important for Beijing.

India, for its part, remains deeply concerned about China’s growing influence in Sri Lanka, which it considers part of its traditional sphere of interest. As China recalibrates its global strategy, it may seek to ease regional tensions with India, potentially stepping back from past hostilities. In this evolving landscape, the groundwork is being laid for improved relations between India and Sri Lanka—an alignment that could help India reclaim its influence in the region. At the same time, it offers Sri Lanka a valuable escape from the strategic and economic trap it has been struggling to navigate.