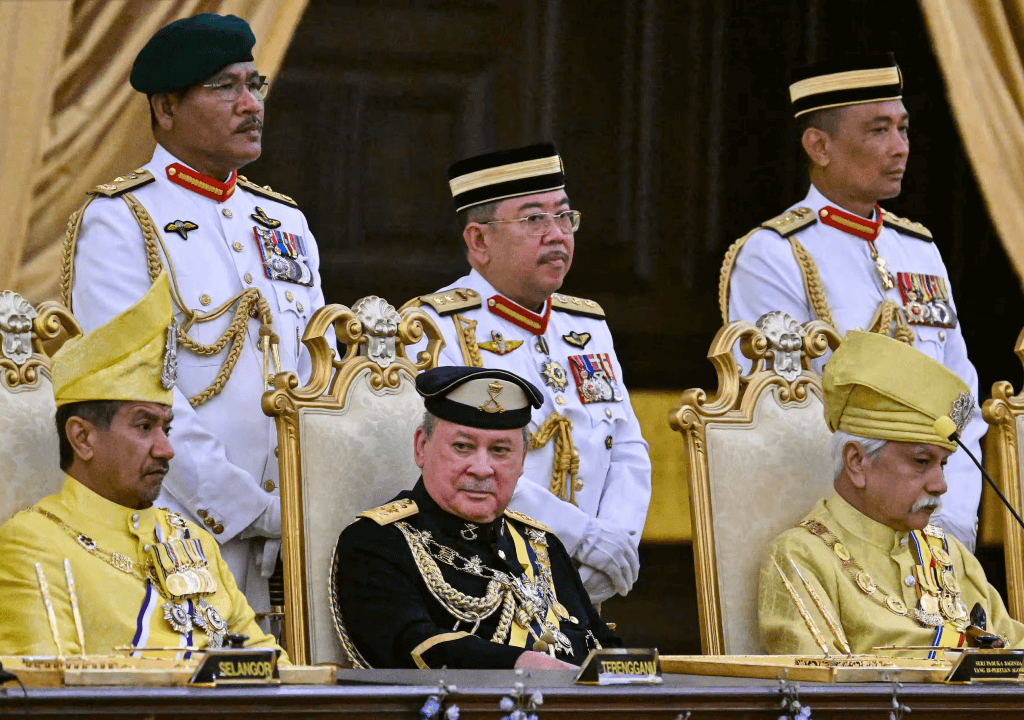

Malaysia welcomed a new Sultan in the person of His Majesty Sultan Ibrahim Iskandar of Johor. With a distinctive blend of business acumen, forthrightness, and cultural heritage, Sultan Ibrahim assumed the esteemed role of the new King of Malaysia in a traditional ceremony held at Istana Negara. Simultaneously, Sultan Nazrin Shah of Perak took the oath of office as the Deputy King. Both rulers earned their positions through election by the Malay Rulers during the 263rd (Special) Meeting of the Conference of Rulers in the previous October, embarking on a five-year term.

The constitutional monarchy system in Malaysia, embraced by the country’s monarchies, is deeply rooted in a political framework that combines elements of the Westminster parliamentary system with features of a federation.

While Malaysia is among the 43 nations practicing a constitutional monarchy, its unique rotational system sets it apart globally. This system involves the selection of a king from among the nine Malay rulers. The momentous occasion unfolded in the Balairung Seri (Throne Room), where 65-year-old Sultan Ibrahim and 67-year-old Sultan Nazrin Shah pledged their oaths and formally assumed their responsibilities. This took place in the presence of fellow Malay Rulers, Regents, and dignitaries from various sectors.

Nine states in Malaysia are led by traditional Malay rulers, collectively known as the Malay states. The eligibility for these thrones is restricted by state constitutions to male Malay Muslims of royal lineage. Among these states, seven follow hereditary monarchies based on agnatic primogeniture: Kedah, Kelantan, Johor, Perlis, Pahang, Selangor, and Terengganu. In Perak, the throne rotation involves three branches of the royal family, loosely following agnatic seniority. Negeri Sembilan stands as an elective monarchy, where the ruler is chosen from male members of the royal family by hereditary chiefs. All rulers, with the exception of those in Perlis and Negeri Sembilan, hold the title of Sultan. The ruler of Perlis is addressed as the Raja, while the ruler of Negeri Sembilan is known as the Yang di-Pertuan Besar.

Every five years, or in the event of a vacancy, the rulers convene in the Conference of Rulers (Malay: Majlis Raja-Raja) to collectively elect the Yang di-Pertuan Agong. This federal constitutional monarch assumes the role of the head of state for Malaysia. Since the Yang di-Pertuan Agong is elected from among the rulers, Malaysia, as a whole, is considered an elective monarchy.

Each of the nine rulers in Malaysia serves as both the head of state for their respective state and the leader of the Islamic faith within that state. Similar to constitutional monarchs globally, these rulers do not directly engage in the administration of their states. Instead, conventionally, they are obliged to act upon the advice of their state’s head of government, known as the Menteri Besar (plural: Menteri-menteri Besar). While the ruler has discretionary powers in appointing the Menteri Besar, who must command a majority in the state legislative assembly, and can refuse a dissolution of the state assembly upon the Menteri Besar’s request, the monarch’s powers have been progressively restricted over time, though the precise limits remain a subject of debate.

The Yang di-Pertuan Agong holds the position of the federal head of state in Malaysia and fulfils symbolic roles, including serving as the Commander-in-Chief of the Malaysian Armed Forces and engaging in diplomatic functions like hosting foreign diplomats and representing Malaysia on state visits. Additionally, the Yang di-Pertuan Agong serves as the head of Islam in his own state, the four states without rulers (Penang, Malacca, Sabah, and Sarawak), and the Federal Territories.

As part of the responsibilities, the Yang di-Pertuan Agong is required to delegate all state powers, excluding the role of the head of Islam, to a regent. Similar to other rulers, the Yang di-Pertuan Agong follows the advice of the Prime Minister, exercising discretionary powers in the appointment of the Prime Minister. The appointed Prime Minister must command a majority in the Dewan Rakyat, the lower house of Parliament.

Furthermore, the Yang di-Pertuan Agong is involved in the appointment of the Yang di-Pertua Negeri, who serves as ceremonial governors for the four states without rulers. This appointment is made based on the advice of the Prime Minister and the Chief Ministers of the respective states.

While the sultan may not have a direct role in the country’s governance, they wield significant authority that can shape the political landscape. One crucial authority is the monarch’s power to grant pardons, exemplified in 2018 when Sultan Muhammad V pardoned Anwar Ibrahim, who had previously served a prison term for sodomy-related charges and now holds the position of Malaysia’s prime minister. Amid the escalating feud between Mahathir and Anwar, and mounting cases against Mahathir and allies, the new Sultan Ibrahim assumes importance as a key authority.

Royal intervention has played a pivotal role in naming prime ministers three times following government collapses and post-election hung parliaments in recent years. Accusations of movements to topple the government highlight the importance of royal intervention in making crucial decisions. In a December interview with Singapore’s The Straits Times, the 65-year-old Sultan expressed his reluctance to be a “puppet king,” emphasizing his alignment with the people rather than being confined to parliamentary dynamics. He asserted his willingness to support the government while reserving the right to voice concerns if he perceives any improper actions.

Maintaining a close association with Anwar, Sultan Ibrahim has been outspoken on Malaysian political affairs and corruption issues. The Sultan’s role is poised to be significant in shaping the country’s trajectory in the coming years.