As Democracy Waits, Bangladesh Extends Interim Rule Until 2026 Election

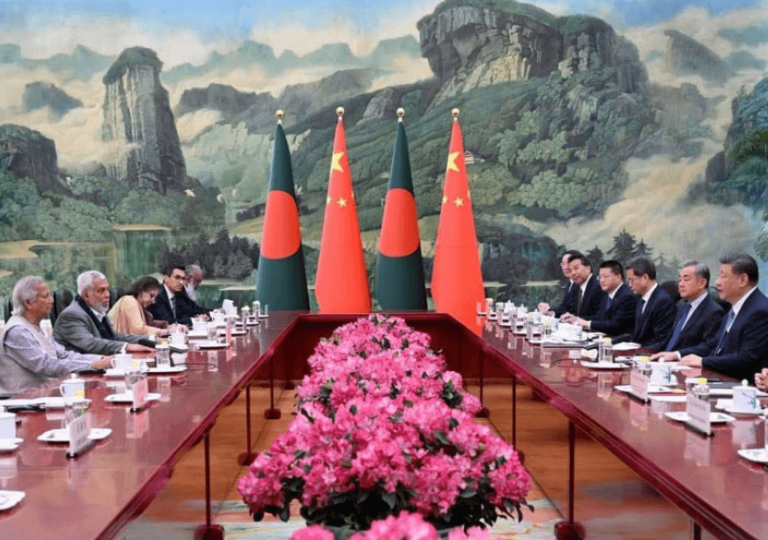

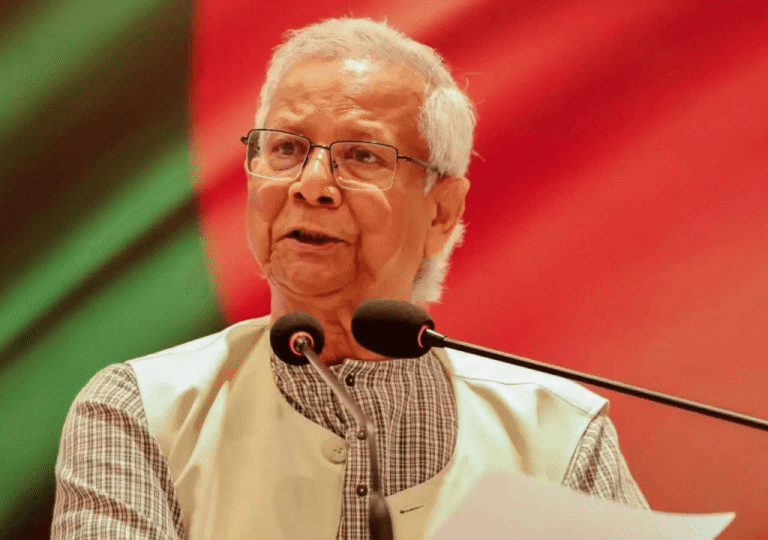

Bangladesh has announced its next general election will be held in April 2026, extending the rule of the interim government that replaced Sheikh Hasina’s administration in August last year.