Can Thailand and Cambodia Find Peace After the Truce?

After the truce, the border between Thailand and Cambodia remains tense. Discover the challenges and possibilities for peace between the two nations.

After the truce, the border between Thailand and Cambodia remains tense. Discover the challenges and possibilities for peace between the two nations.

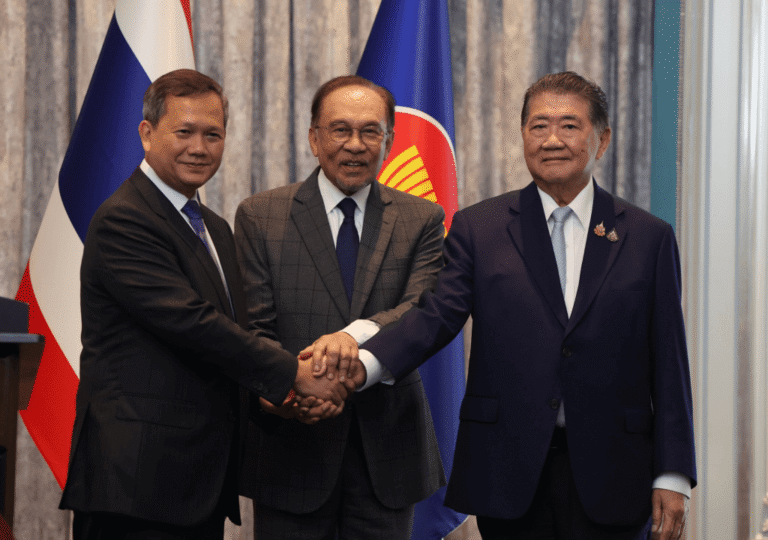

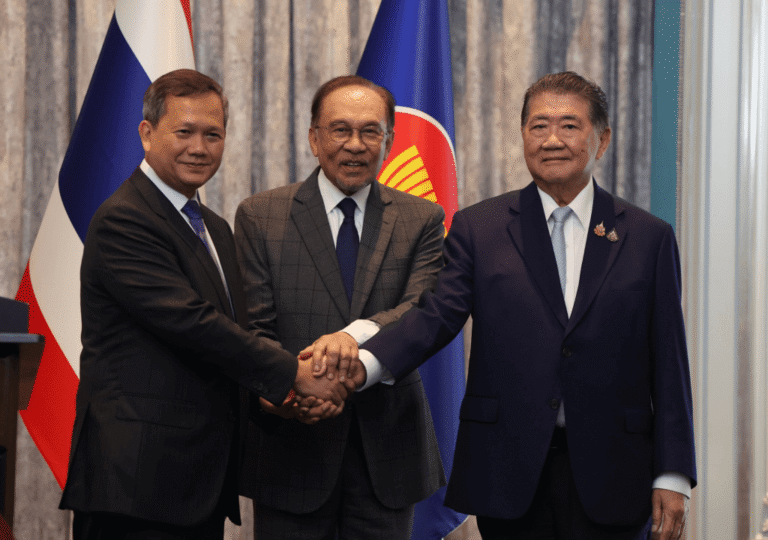

Southeast Asian nations are seeking a unified meeting with Trump to address U.S. tariffs while pushing for greater regional integration. Can ASEAN overcome internal differences to act as one?

Cambodia's authoritarian regime, led by Hun Sen, silences dissent and imprisons opposition leaders like Sun Chanthy

Cambodia's rising anti-Vietnamese sentiment is fueled by historical grievances and current border disputes, leading to protests and political tensions

Cambodian court jails 10 Mother Nature activists for 6-8 years in blow to civil society.

Cambodia's Senate election, dominated by the ruling party, foreshadows a predetermined outcome, reinforcing dynastic power dynamics, undermining democratic principles.