What Modi’s Heroic Welcome in the Maldives Says

Modi’s high-profile visit to the Maldives reflects deepening ties between the two nations and suggests a regional realignment amid growing uncertainty around Chinese influence.

Modi’s high-profile visit to the Maldives reflects deepening ties between the two nations and suggests a regional realignment amid growing uncertainty around Chinese influence.

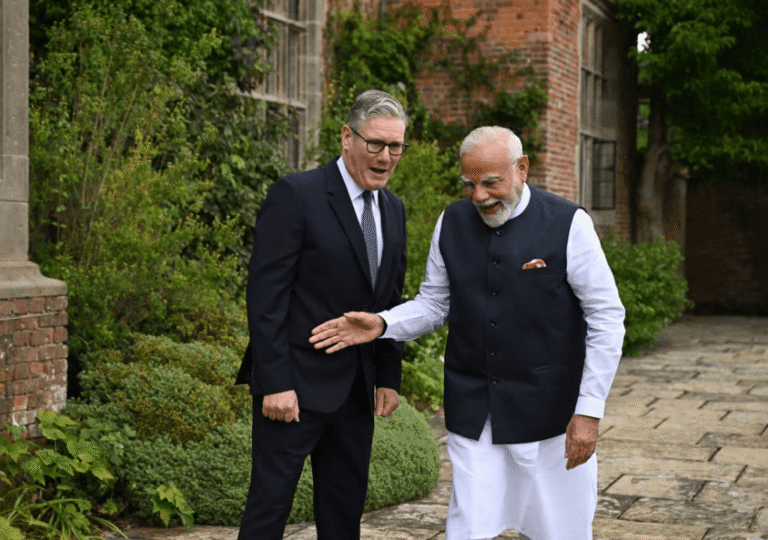

The UK India Trade Agreement 2025 has finally been signed. Explore the key terms of the deal, its impact, and who stands to benefit most.

Despite making electoral gains in 2024, India’s opposition alliance is now showing cracks. What caused this fragmentation, and what does it mean for the future of Indian democracy?

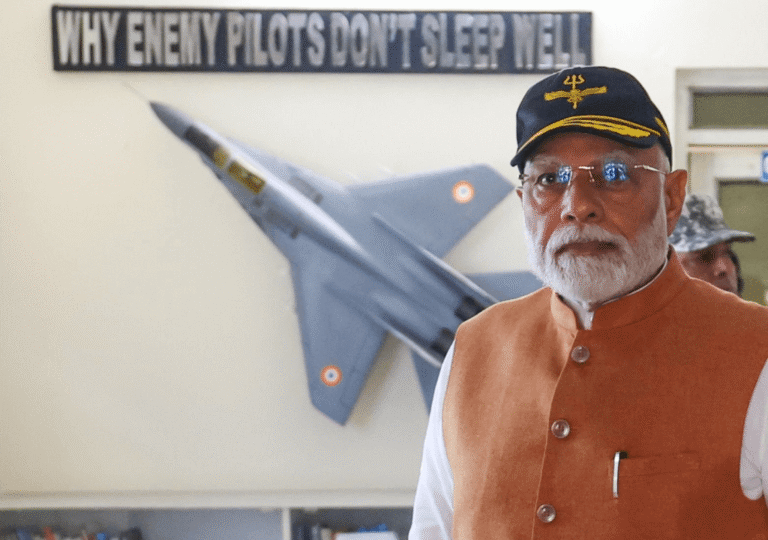

Discover how the recent military and diplomatic escalation between India and Pakistan reshaped domestic politics in both countries—strengthening leadership narratives, influencing public opinion, and shifting electoral strategies.

India and Canada are cautiously working to restore diplomatic ties after years of strain during Justin Trudeau’s leadership. With new leadership in Ottawa, both nations signal a fresh start through high-level engagement and dialogue.

A detailed exploration of the diplomatic strain between India and Turkey amid recent geopolitical developments.

Despite a ceasefire, India and Pakistan remain locked in a fierce disinformation war, with media and officials fueling competing narratives.

The United Kingdom and India have finalized a landmark trade agreement after three years of intense negotiations. The deal is set to boost both economies, fostering new trade opportunities and strengthening bilateral ties.

India carried out cross-border missile strikes against Lashkar-e-Taiba in a decisive retaliation to terrorist aggression originating from Pakistan.

As Kashmir violence reignites India-Pakistan tensions, the Indian government maintains a calculated calm. While the media speculates on war, New Delhi opts for restraint and strategic pressure over open conflict.