Can Thailand and Cambodia Find Peace After the Truce?

After the truce, the border between Thailand and Cambodia remains tense. Discover the challenges and possibilities for peace between the two nations.

After the truce, the border between Thailand and Cambodia remains tense. Discover the challenges and possibilities for peace between the two nations.

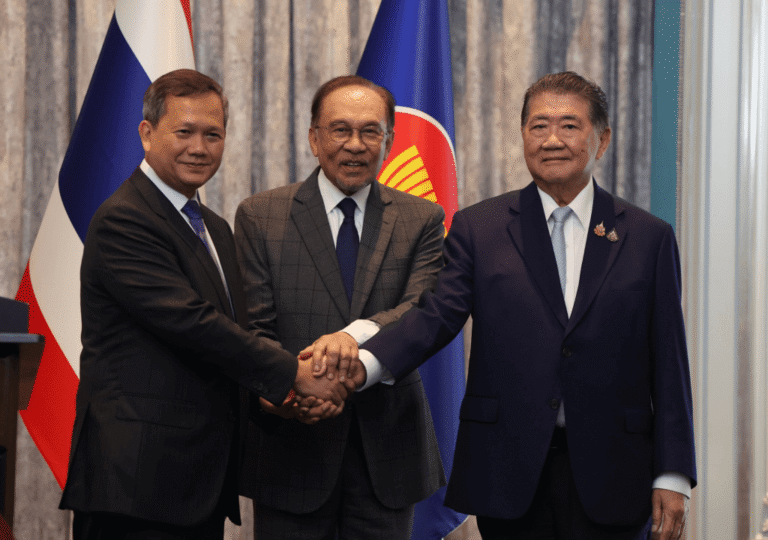

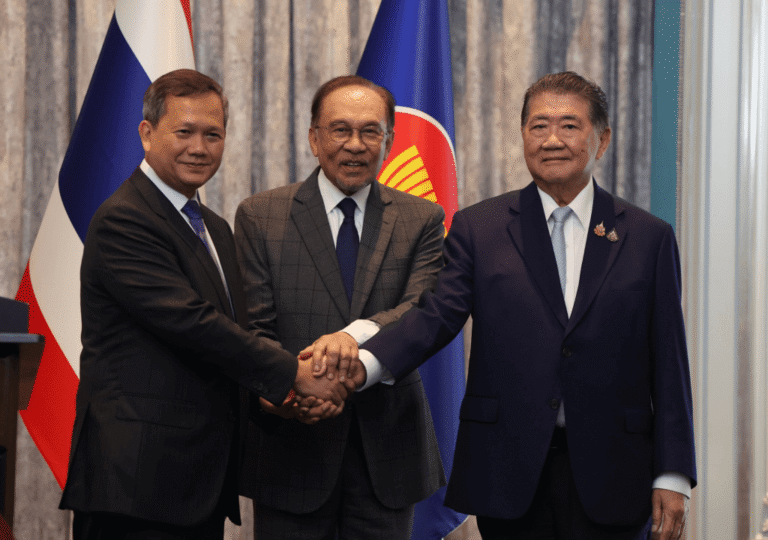

Southeast Asian nations are seeking a unified meeting with Trump to address U.S. tariffs while pushing for greater regional integration. Can ASEAN overcome internal differences to act as one?

The insurgency in southern Thailand has flared up again, raising concerns about escalating violence. Explore the factors driving the conflict and what the future may hold for the region.

Malaysia and Singapore have launched the Johor-Singapore Special Economic Zone to boost bilateral ties and attract global investment

Malaysia charges ex-PM Muhyiddin with sedition over alleged remarks about former king

Malaysia's strategic position and semiconductor investments align it with U.S. interests, potentially joining Asian NATO

Malaysia adopts orangutan diplomacy to showcase commitment to nature conservation and ease concerns over palm oil deforestation.

In Malaysia and Indonesia, Islamic parties gain momentum, reshaping politics toward conservatism amid societal shifts, potentially altering national identities.

Former Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak's prison sentence for embezzling RM42 million reduced by the Federal Territories Pardons Board, sparking concerns about transparency and the nation's anti-corruption image.

Sultan Ibrahim Iskandar assumes the role of Malaysia's new King, emphasizing alignment with the people and expressing reluctance to be a "puppet king." Royal intervention remains crucial in shaping political decisions.