Facing Financial Strain, Pakistan Prioritizes Defense in New Budget

Despite facing severe economic challenges and rising debt, Pakistan’s 2025–26 budget increases military spending by nearly 20%, drawing public and expert concern.

Despite facing severe economic challenges and rising debt, Pakistan’s 2025–26 budget increases military spending by nearly 20%, drawing public and expert concern.

As countries engage diplomatically with the Taliban, concerns grow over the lack of progress on human rights. Is the Islamic Emirate inching toward global recognition despite these issues?

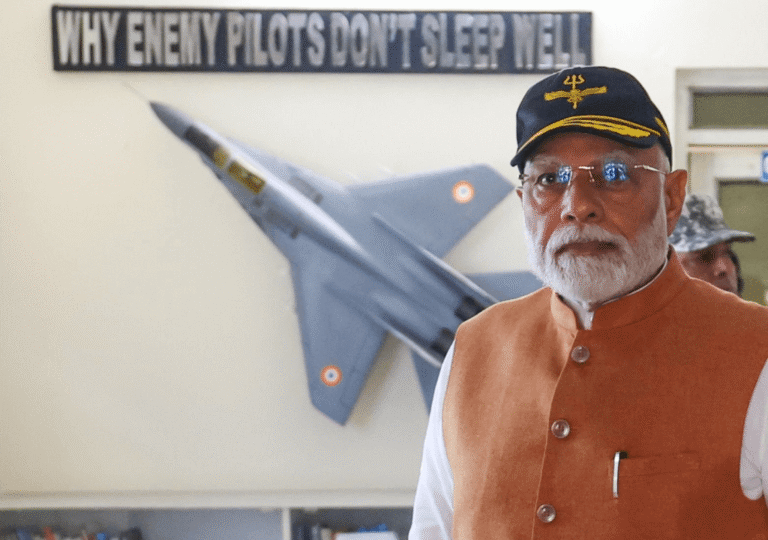

Discover how the recent military and diplomatic escalation between India and Pakistan reshaped domestic politics in both countries—strengthening leadership narratives, influencing public opinion, and shifting electoral strategies.

A detailed exploration of the diplomatic strain between India and Turkey amid recent geopolitical developments.

Despite a ceasefire, India and Pakistan remain locked in a fierce disinformation war, with media and officials fueling competing narratives.

India carried out cross-border missile strikes against Lashkar-e-Taiba in a decisive retaliation to terrorist aggression originating from Pakistan.

As Kashmir violence reignites India-Pakistan tensions, the Indian government maintains a calculated calm. While the media speculates on war, New Delhi opts for restraint and strategic pressure over open conflict.

A deadly attack on Hindus in Kashmir has intensified tensions between India and Pakistan, pushing the region closer to a potential conflict. The growing unrest threatens to destabilize the fragile peace in South Asia.

As relations with Afghanistan deteriorate, Pakistan intensifies its crackdown on Afghan refugees, heightening tensions with Kabul.

Balochistan is witnessing escalating violence and deepening political divisions, with a rising death toll and increasing instability.