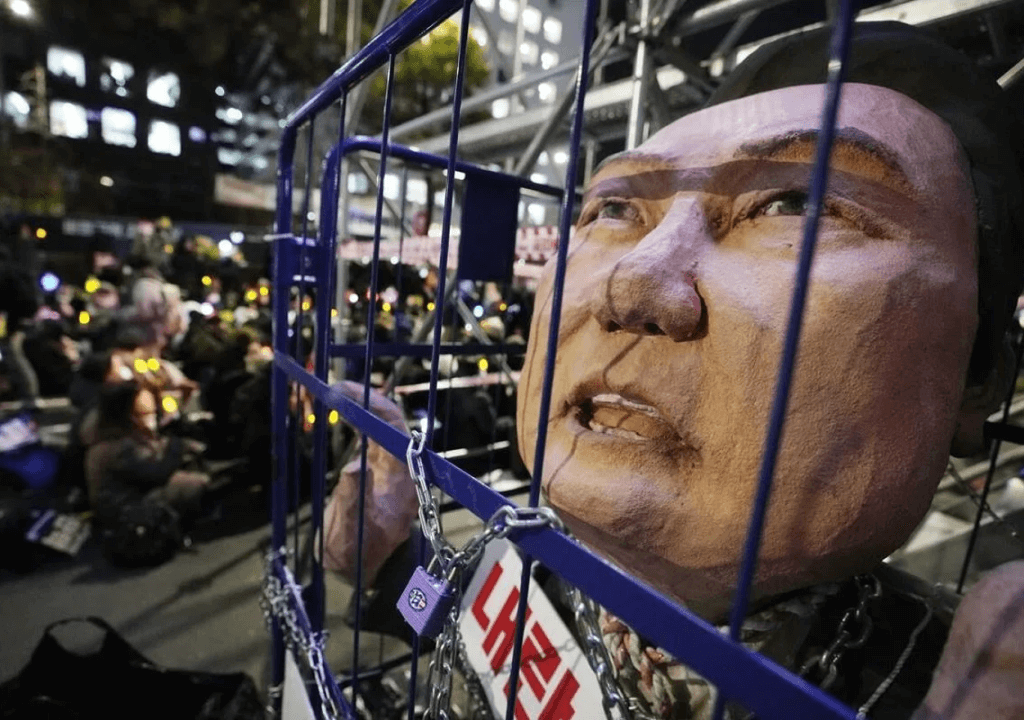

The president who declared martial law and attempted to shutter parliament has finally been decisively ousted. The political drama that has gripped South Korea since December is now approaching its climactic turn. In the peak moment of this saga, for 22 breathless minutes, millions across the nation listened as Chief Justice Moon Hyung-bae of the Constitutional Court delivered the verdict in the impeachment of Yoon Suk Yeol—an outcome shaped by the president’s chaotic and authoritarian bid to consolidate power. The wait was excruciating, the atmosphere almost theatrical.

The court’s ruling on Friday may have offered a fleeting sense of institutional redemption. Yet domestically, the country remains deeply fractured. The verdict that ousted the president is far from the final act. The saga will continue—perhaps as another season in a long-running national reckoning. The decision has now triggered a 60-day countdown to elect a new president, with the date to be announced within ten days by Acting President Han Duck-soo.

A landmark verdict

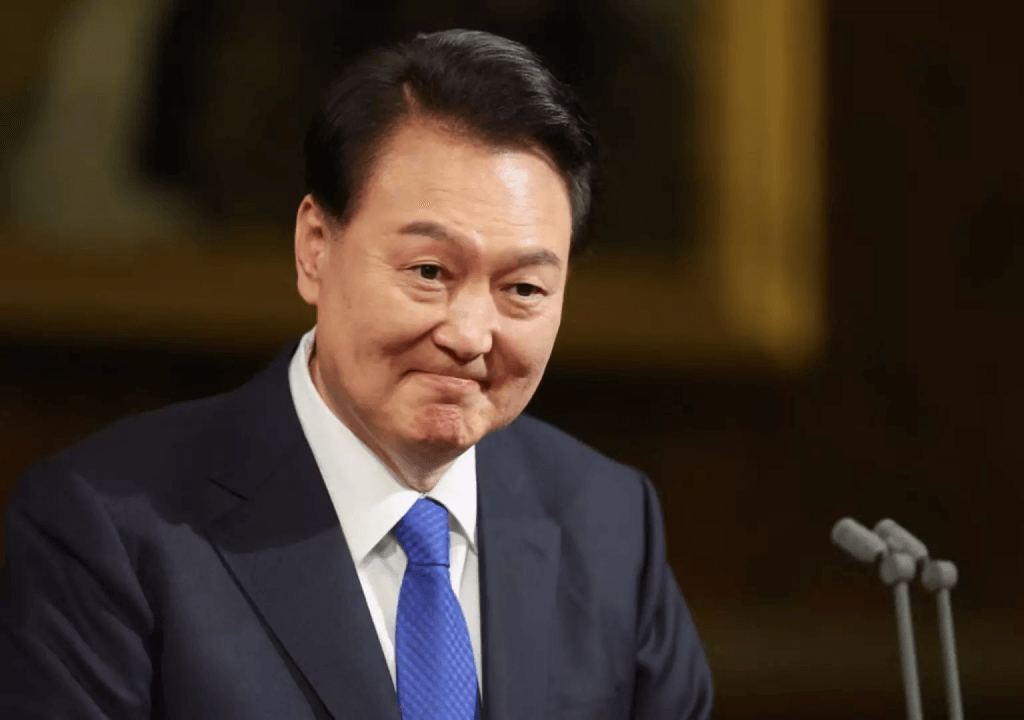

The Constitutional Court’s decision marks a pivotal juncture in South Korea’s democratic history. With each damning sentence, Chief Justice Moon Hyung-bae gave voice to a public long demanding the permanent removal of the suspended president. Crowds gathered outside the court hung on every word, their anticipation mounting as Moon methodically laid out the case against Yoon Suk Yeol.

Moon declared that Yoon’s actions posed a direct threat to democracy. He asserted that the 64-year-old conservative populist had gravely betrayed the public’s trust, plunging the nation into its most destabilizing political crisis since its democratic transition in the late 1980s. When the Chief Justice finally pronounced that President Yoon was officially removed from office, the crowd outside erupted in cheers.

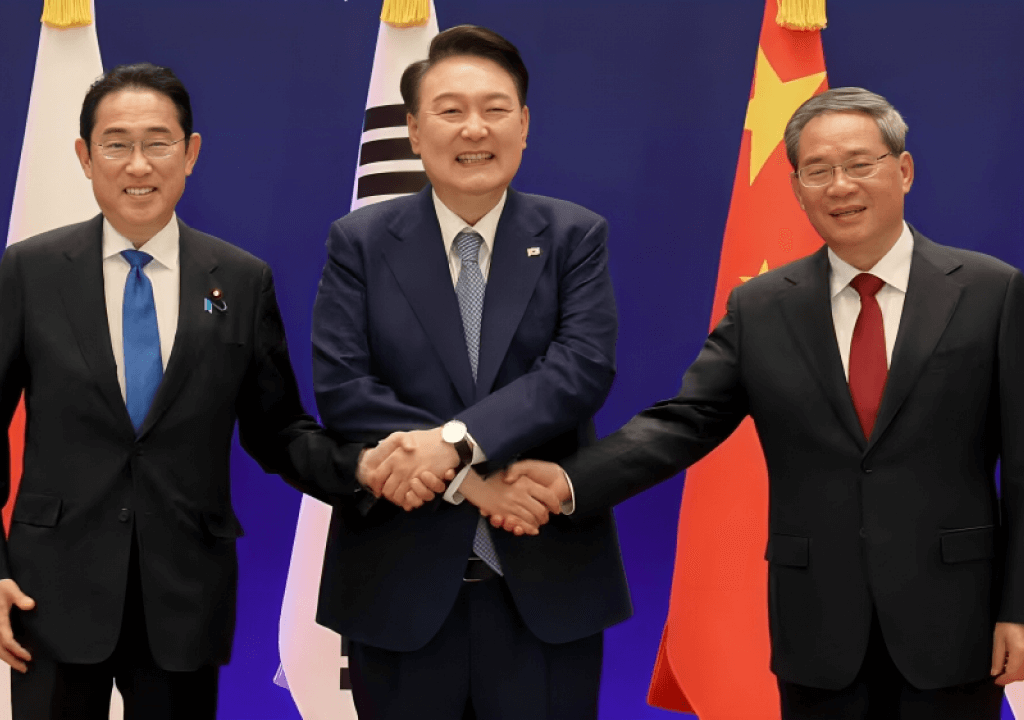

According to Moon, Yoon’s declaration of martial law had sown widespread chaos, damaging both the economy and foreign relations. He emphasized that Yoon not only imposed martial law without legitimate cause but also violated the constitution by using military and police forces to obstruct the legislature. This, Moon concluded, constituted a flagrant abuse of emergency powers and a collapse of constitutional order.

The Chief Justice stressed that the severity of Yoon’s violations—both in terms of constitutional principles and their broader political consequences—made his removal necessary. The decision, though deeply disruptive, was framed as essential to preserving democratic integrity.

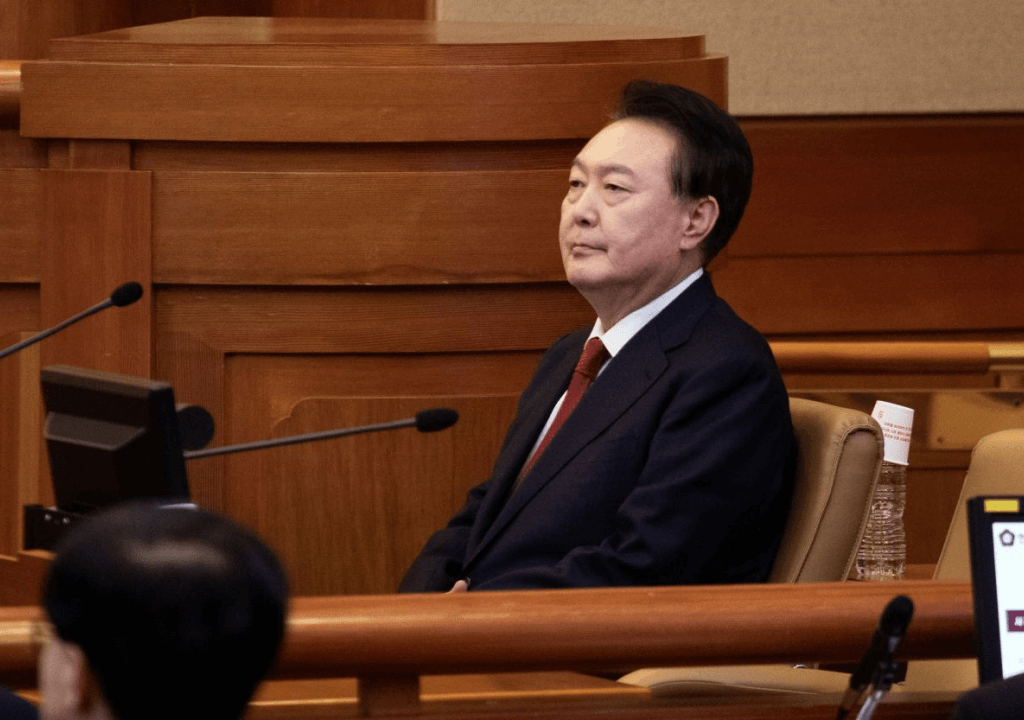

Yoon, who did not appear in court for the ruling, has no right to appeal. He now faces a separate criminal trial on charges of insurrection—a dramatic final chapter to a presidency undone by its own authoritarian excesses.

The election is coming.

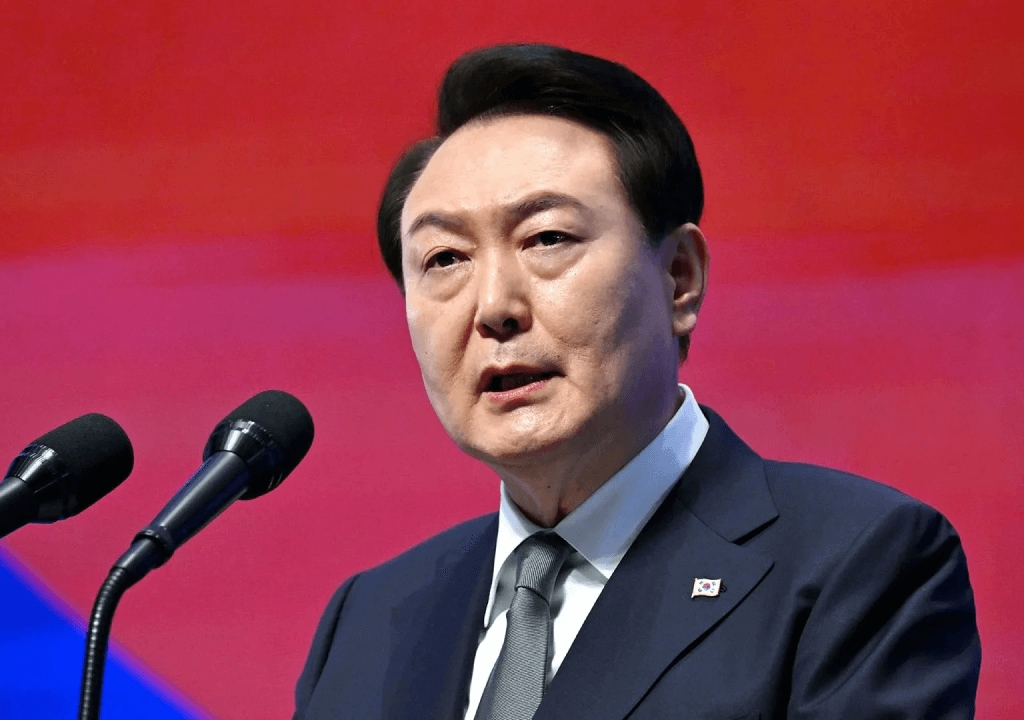

South Korea’s turbulent political climate now shifts toward a high-stakes presidential election, set in motion by the impeachment of President Yoon Suk Yeol. Acting President Han Duck-soo is expected to announce the election date in the coming days. Although the legal process has advanced, the political atmosphere remains deeply fraught, with the public starkly divided.

Political parties are racing to field competitive candidates, with the Democratic Party’s Lee Jae-myung currently leading in the polls. In contrast, Yoon’s conservative People Power Party faces a formidable task: finding a nominee who is either free from association with the disgraced administration or capable of channeling the strongman persona that once galvanized Yoon’s base.

During his presidency, Yoon often leaned on Cold War-era rhetoric, branding opponents as pro–North Korean or anti-state—language that analysts believe only deepened national polarization. As the party charts its path forward, any potential candidate will need to navigate this fractured landscape by studying Yoon’s core supporters and tailoring a message that resonates with them.

Unsettled division

The ongoing clashes between South Korea’s rival political factions present a profound challenge to the country’s democratic foundations. While friction between a president and a parliament controlled by opposing parties is not unusual, the current level of animosity has taken a deeply unsettling turn. The National Assembly has become a battleground, a reflection of the broader dysfunction consuming the nation’s political discourse.

When the Assembly held its initial impeachment vote in December, it offered the People Power Party a chance to distance itself from President Yoon Suk Yeol. Instead, its lawmakers boycotted the vote and reaffirmed their loyalty to the embattled leader. In doing so, they lent credence to Yoon’s widely discredited claims that recent elections—including a parliamentary vote earlier in the year—had been tainted by fraud.

Such rhetoric found a receptive audience among Yoon’s supporters, who echoed Donald Trump’s “Stop the Steal” slogans as they poured into the streets. Conspiracy theories, once confined to the margins, quickly moved to the heart of political protest.

Whoever takes office in the upcoming presidential election will inherit the unenviable task of bridging a deeply polarized society and restoring trust in democratic institutions—institutions that many believe Yoon systematically undermined.

Conservatives in Trouble

The Constitutional Court’s ruling brings a dramatic close to the turbulent three-year presidency of Yoon Suk Yeol, a conservative populist whose rise and downfall are now framed by impeachment. After narrowly defeating liberal candidate Lee Jae-myung in the 2022 election, Yoon was initially seen as a bold, no-nonsense leader poised to cut through political deadlock and restore order to a weary electorate. But what once seemed like strength soon hardened into inflexibility. His presidency became defined by relentless confrontation—battling an opposition-led National Assembly, targeting critical journalists, clashing with striking medical workers, and obstructing probes into corruption allegations involving his wife, Kim Keon Hee. His rhetoric grew increasingly incendiary, casting political opponents as criminals and accusing them of colluding with North Korea, echoing the paranoia of South Korea’s Cold War past.

In the wake of the ruling, the People Power Party issued a restrained statement, calling the verdict regrettable while affirming its respect for the Constitutional Court’s decision. The party also extended a formal apology to the public. Meanwhile, Yoon’s legal team denounced the decision as unconstitutional and demanded his immediate reinstatement. But public sentiment had already turned decisively against him. A Gallup Korea poll released just days before the verdict found that 60 percent of South Koreans supported his permanent removal from office.

With the political winds shifting sharply against the conservatives, Yoon’s party now faces an uphill battle as it braces for the upcoming presidential election.

The saga continues

The political saga is far from over. Few believe that either the candidates or the electorate in the upcoming presidential election will be able to move beyond the bitterness of the past four months. Yoon’s future also looms as a troubling uncertainty in South Korean politics. He now faces a separate criminal trial on charges of insurrection—a grave offense that carries the possibility of life imprisonment or even the death penalty, although no executions have been carried out in South Korea since the late 1990s. Despite his removal from office, Yoon continues to command a fiercely loyal base, and how his supporters respond in the coming weeks will be closely watched. As the country approaches the polls, the political landscape remains deeply fractured. A liberal victory appears increasingly likely, while the conservative camp is gripped by internal doubts and public distrust. And The climate of hostility shows little sign of dissipating.