Trump’s Syria Bet: From ‘Terrorist’ to Trusted Ally?

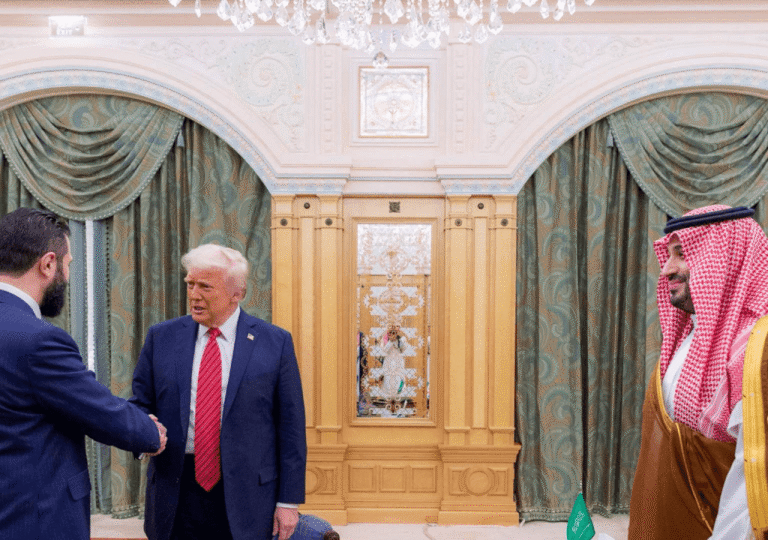

After lifting U.S. sanctions, Donald Trump met Syria’s new Islamist president Ahmed al-Sharaa in a high-profile summit. Explore the strategic motives and implications behind this unexpected diplomatic shift.