The Taliban, an Islamist extremist group, has been ruling Afghanistan as the “Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan” since overthrowing the internationally recognized Islamic Republic in 2021. The sudden and forceful takeover shocked the world, with unforgettable images of civilians clinging to planes and desperate attempts to flee the country as the former government collapsed.

Despite the passage of time, no country has formally recognized the Taliban regime, which enforces a strict version of Islamic law widely criticized for violating modern principles, particularly in its treatment of women, children, and minority groups. Basic human rights continue to be denied under their rule.

Still, the Taliban has campaigned for international recognition, gradually taking control of Afghanistan’s foreign embassies and maintaining limited diplomatic contacts. Some countries have accepted Taliban-appointed diplomats or sent new ambassadors, even without officially recognizing the regime.

Is the world beginning to overlook the Taliban’s record and quietly move toward accepting their rule in Afghanistan?

Islamic nations at the forefront

The Taliban’s return to power in Kabul—whether planned or not—sparked global unease. While most governments condemned the group’s ascent in 2021, a few—most notably Pakistan—welcomed the development, framing it as a symbolic end to foreign interference and a revival of Islamic governance.

Pakistan, which has long-standing ties with the Taliban, was among the few countries—along with the UAE and Saudi Arabia—that formally recognized the regime during its earlier rule from 1996 to 2001. When the Taliban returned, Pakistan once again responded positively. Following extended discussions, it recently deepened its diplomatic engagement by appointing an ambassador to Kabul—a move that the Taliban swiftly reciprocated. For many observers, full diplomatic recognition from Pakistan now appears increasingly likely, reaffirming its enduring support across both periods of Taliban rule.

Qatar is another country that may eventually recognize the Islamic Emirate. It has hosted the Taliban’s Political Office in Doha since 2012, serving as the group’s primary diplomatic base. Since the Taliban’s return to power, they have assumed control of the Afghan Embassy in Doha, and Acting Foreign Minister Amir Khan Muttaqi has visited Qatar more than any other country. While Qatar has yet to grant formal recognition, it continues to engage the Taliban diplomatically.

The United Arab Emirates has also moved toward normalization. Its embassy in Kabul reopened in November 2021, and it has hosted high-level Taliban officials in a series of meetings. In August 2024, the UAE accepted a Taliban-appointed ambassador and allowed the group to open a consulate in Dubai—clear signs of warming relations, even without formal recognition.

Saudi Arabia has adopted a more cautious stance. Although it evacuated its diplomats during the Taliban’s return to power, it quietly reopened its embassy in Kabul for consular services in late 2021. By December 2024, it officially resumed full embassy operations under Taliban rule, signaling a measured re-engagement.

Despite initial criticism, Iran formally accredited the Taliban’s envoy and handed over control of the Afghan embassy in Tehran in early 2023. Bangladesh is likely to expand its engagement with the Taliban regime, amid the growing influence of political Islam in its domestic politics. In Central Asia, Turkmenistan accepted a Taliban-appointed envoy in 2022. Uzbekistan took an even bolder step—its prime minister visited Kabul in August 2024, the highest-level foreign visit since the Taliban’s return, followed by the appointment of a new ambassador.

Tajikistan, however, stands out as a vocal opponent. As Afghanistan’s northern neighbor, it continues to designate the Taliban as a terrorist organization and firmly opposes diplomatic recognition. President Emomali Rahmon has repeatedly condemned the Taliban’s failure to establish an inclusive government. The Afghan embassy in Dushanbe remains under the control of envoys from the former Islamic Republic. Yet, signs of pragmatic engagement are emerging: Tajik officials have visited Kabul, and bilateral trade—particularly electricity exports—continues. Still, Dushanbe maintains a cautious stance, portraying itself as a defender of Afghanistan’s Tajik minority and resisting efforts to legitimize Taliban rule.

How powerhouses move

From the beginning, China has adopted a generally supportive stance toward Taliban-led Afghanistan. In the immediate aftermath of the takeover, a spokesperson for China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs emphasized that Beijing respects what it views as the will of the Afghan people and seeks to establish a relationship rooted in friendship and cooperation with the new authorities—setting it apart from most other countries. In the months following the Taliban’s return to power, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi visited Kabul and met with Afghanistan’s acting foreign minister, Amir Khan Muttaqi. In September 2023, China became the first nation to appoint an ambassador—Zhao Sheng—under the new regime. By January 2024, it also became the first to formally accredit a Taliban-appointed envoy, although it has yet to officially recognize the Taliban government.

Moscow has signaled its interest in building ties with the Taliban but has made it clear that formal recognition is not imminent. In September 2021, Russia’s ambassador to Kabul, Dmitry Zhirnov, met with Taliban representatives to discuss the security of the Russian embassy, which remained open throughout the transition. Following a meeting with Taliban officials in Moscow on October 21, President Vladimir Putin indicated that Russia might consider delisting the group as a terrorist organization, but stressed that any such decision should originate from the UN Security Council. On March 31, 2022, Russia became one of the first countries to accept the credentials of a Taliban-appointed envoy, although it has yet to extend formal recognition to the regime.

India has also refrained from recognizing the Taliban-led government. While New Delhi played a significant role in providing aid and development support to Afghanistan during the republic era, it has adopted a cautious stance since the Taliban’s return. The Indian government has expressed its willingness to offer humanitarian assistance when necessary but remains deeply concerned that Afghanistan could once again serve as a base for anti-India militant groups, as it did during the Taliban’s earlier rule. Although there have been reports of backchannel communication, formal diplomatic engagement remains minimal.

The United States, on the other hand, has largely disengaged. Under the Biden administration, Secretary of State Antony Blinken stated that the U.S. would not recognize any government that harbors terrorist groups or fails to uphold basic human rights. This position appears unlikely to change during the Trump era.

Will recognition lead to human rights?

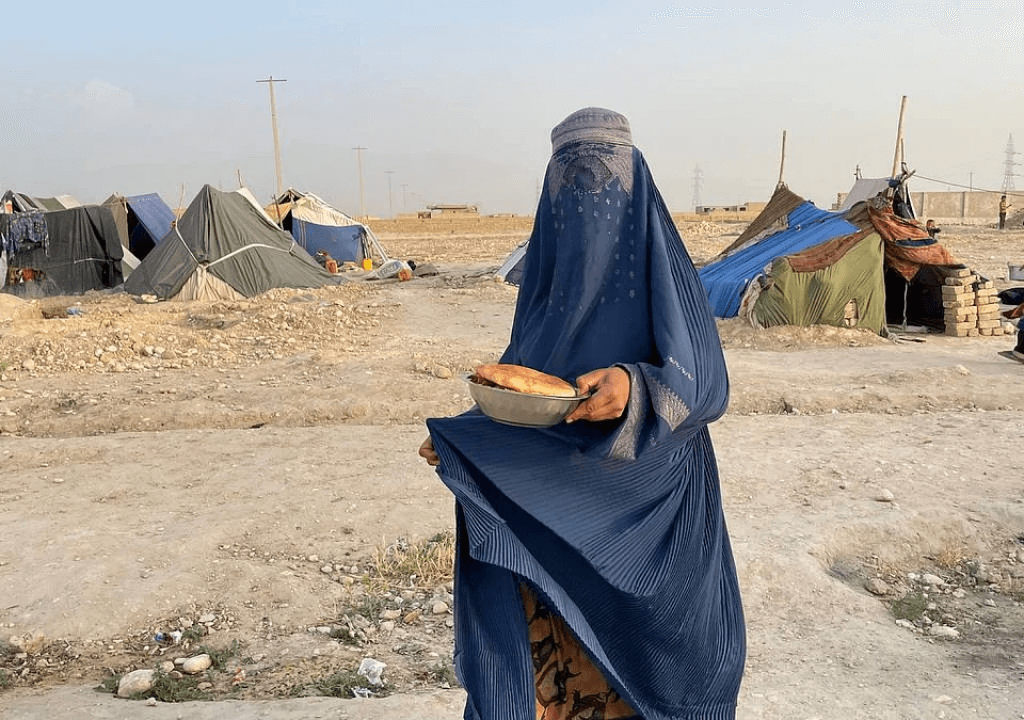

The harrowing images of people clinging to aircraft during the Taliban’s takeover in 2021 starkly revealed the fear many Afghans carried—rooted in the memories of the group’s earlier rule in the 1990s. Although the Taliban and its supporters claimed that their new regime would be different, nearly four years later, little has changed. Conservative Islamic practices still dominate, outdated laws remain in effect, and basic human and minority rights continue to be denied. Women, in particular, remain victims of systemic oppression—barred from education and public life, while tribal customs have been reinstated.

Nevertheless, some humanitarian organizations and left-leaning groups argue that diplomatic recognition of the Taliban could serve as a tool to negotiate better human rights protections. Yet countries like China, Pakistan, and Qatar have already begun strengthening ties with the regime—offering financial lifelines without demanding significant reforms. China is primarily interested in Afghanistan’s mineral wealth, while Pakistan and other Islamic nations express support in the name of religious solidarity. For these governments, human rights are not a priority. As a result, formal recognition may arrive without meaningful negotiations, potentially sidelining the human rights agenda altogether.