It was another deadly episode in the turbulent post-COVID era. Cambodia and Thailand, neighboring countries long marked by mutual hatred and still governed by authoritarian practices, clashed over land rich in cultural heritage. The five-day conflict claimed numerous lives and forced many to flee before a ceasefire was reached. Yet even with the truce in place, tensions remain high. Both sides have accused each other of violating the agreement, while online, public doubt continues to grow, fueled by a volatile mix of disinformation, threats, and rising nationalism.

The long-burning tension

The dispute between Thailand and Cambodia stretches back more than a century, beginning when France, which occupied Cambodia until 1953, first drew the land border. Spanning over 817 kilometers, this boundary has long been a source of tension, as many colonial-era borders in Asia, combined with deep-rooted ethnic divisions and unstable politics, have fueled conflicts and kept the tensions alive to this day.

The latest round of conflict started in May, when troops exchanged fire in a contested area, resulting in the death of a Cambodian soldier. This set off a series of retaliatory measures: Thailand imposed border restrictions on Cambodia, while Cambodia responded by banning imports of Thai fruits and vegetables, halting broadcasts of Thai films, and reducing internet bandwidth from Thailand, among other actions. Tensions escalated further when five Thai soldiers were injured by landmines during patrols. Thailand accused Cambodia of planting new mines, prompting the closure of northeastern border crossings, the withdrawal of Thailand’s ambassador, and the expulsion of Cambodia’s ambassador in protest. Cambodia denied laying new mines but downgraded diplomatic ties to their lowest level and recalled all embassy staff from Bangkok.

Tensions finally boiled over into airstrikes, a war without being officially declared, lasting five days. At least 43 people, including children, were killed on both sides of the border, and almost 300,000 were displaced, marking the worst clash between the two neighboring nations in over a decade.

Politics that stir trouble

It must be said that both governments, whose leaders heavily rely on nationalism and stoke patriotic fervor, have made little genuine effort to resolve the underlying issues and often contribute to the tensions. Cambodia is effectively a one-party state, ruled by authoritarian leader Hun Sen for nearly four decades before passing power to his son, Hun Manet, in 2023. Hun Sen now serves as president of the senate but remains highly influential, likely using nationalist sentiment to bolster his son’s position.

Meanwhile, in Thailand, citizens are pushing for greater freedom and reforms to the traditional royal-linked governance. For the Thai government, keeping nationalist tensions alive helps unite the population and blocks the rise of alternative political movements long sought by the people.

And together they make it possible.

A clash like this would create serious economic problems for both nations. A war would damage Thailand’s reputation as a tourist destination and further strain Cambodia’s economy, which heavily depends on remittances from workers in Thailand. Before the conflict, over 520,000 Cambodians were employed in Thailand, mostly in low-paid jobs in agriculture, construction, fishing, and manufacturing. The situation is compounded by sanctions imposed by the U.S. President Trump, adding another layer of economic pressure. While a government accountable to its citizens might struggle under such conditions, authoritarian regimes often redirect public frustration toward perceived national threats.

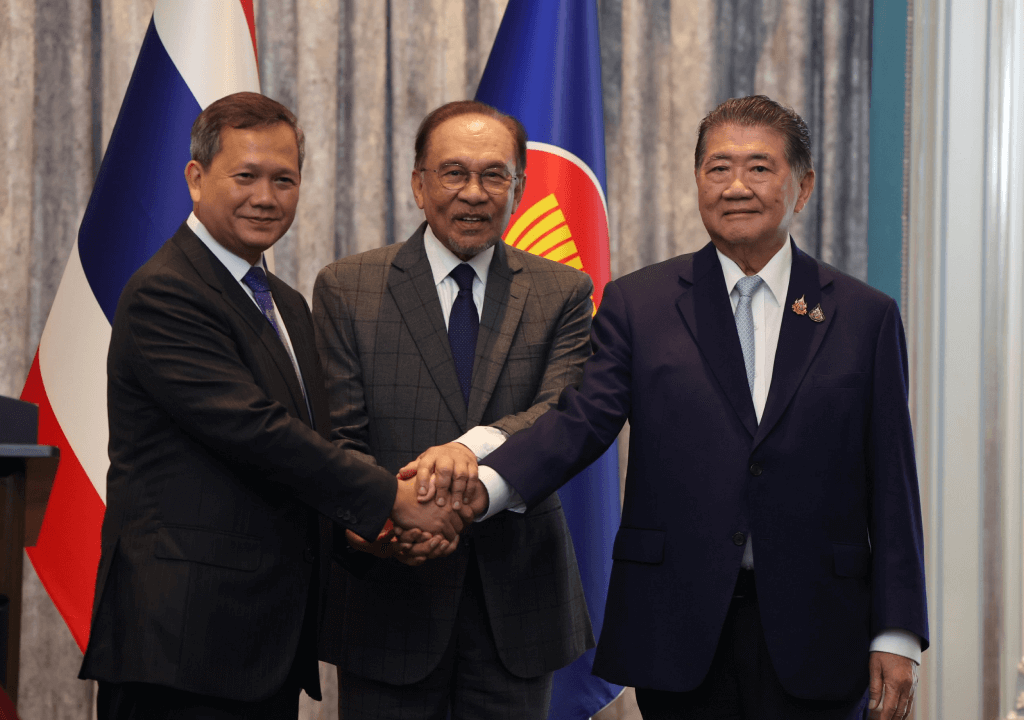

The scope of peace after the truce

A truce came into effect in August, with credit given to Anwar Ibrahim, the Prime Minister of Malaysia, which currently chairs ASEAN, and Donald Trump for helping mediate the agreement. While there are no active strikes at present, reports from the border, including an incident in which three Thai soldiers were injured when one tripped a landmine along the frontier with Cambodia, have dampened hopes for lasting peace.

Two days after the countries met in Malaysia to sign a 13-point agreement implementing the ceasefire, the Thai army said the latest landmine incident was a significant obstacle to carrying out the ceasefire measures and achieving a peaceful resolution. Cambodia’s Mine Action and Victim Assistance Authority responded that it has not planted any new landmines and has no intention of doing so.

It appears that the authoritarian governments in both countries have little incentive to pursue lasting peace. With no meaningful compromise from either side, tensions remain high and the risk of another round of strikes persists. The Prasat Preah Vihear Temple, an 11th-century Hindu temple and UNESCO World Heritage site, sits at the center of the disputed area and could face further conflicts from both sides.