For decades, South Korea has held itself up as a beacon of democracy, emerging from the shadows of authoritarianism to embody the principles of freedom and justice on a divided peninsula. But under President Yoon Suk Yeol, that proud narrative began to unravel. By declaring martial law, dissolving parliament, and clinging to power with an iron-fisted resolve, Yoon thrust the nation into a crisis that sent shockwaves through both allies and adversaries alike.

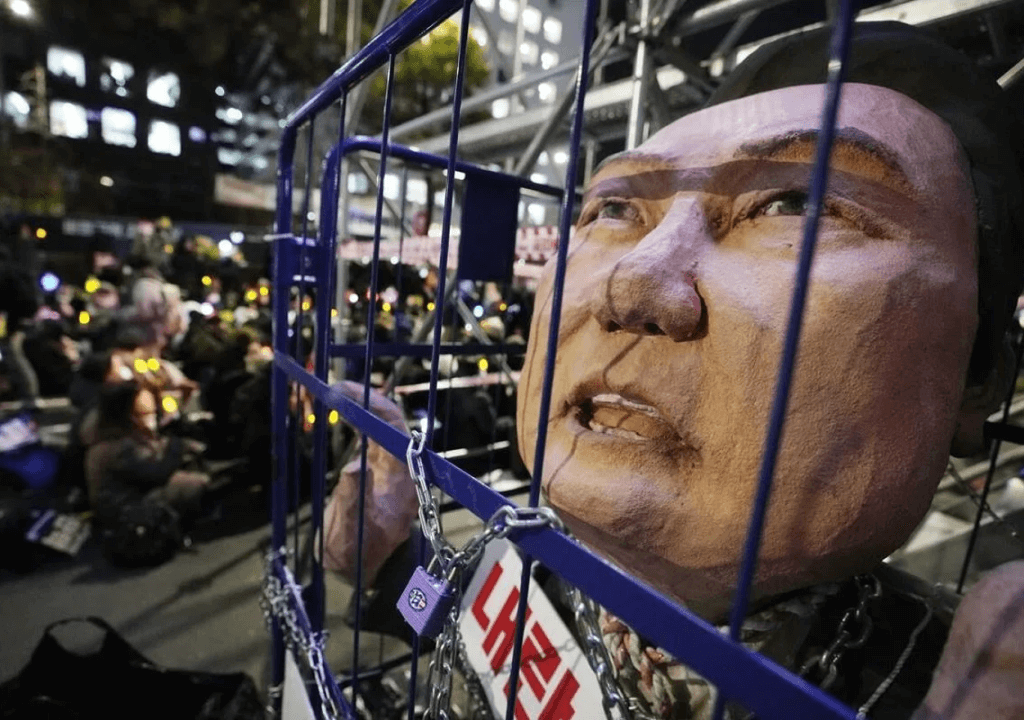

The backlash was swift and relentless, sweeping through the streets and digital platforms. Protesters took to the streets, while online voices drew troubling comparisons between Yoon’s South Korea and its northern neighbor, eroding the country’s hard-won status as a democratic model. What had taken years to build was on the verge of collapse.

As public outrage grew, a fractured parliament made its first attempt at impeachment. Yoon stood firm, refusing to resign. Only after a second, decisive vote did his impeachment succeed. In that moment, South Korea glimpsed hope at the end of a prolonged political crisis and further humiliation.

On Saturday, South Korea’s National Assembly made the historic move, passing an impeachment motion against President Yoon Suk Yeol just days after his controversial declaration of martial law—an act overturned within hours. Yet, Yoon’s fate now lies not in the hands of legislators, but with the Constitutional Court, which must determine whether the impeachment is valid. The stakes are high: the court has up to 180 days to deliberate, and its decision could reinstate Yoon, cement his removal, or leave the nation in further uncertainty.

Precedents loom large in the minds of the South Korean public. In 2004, the court rejected the impeachment of Roh Moo-hyun, allowing him to resume his presidency. Conversely, in 2017, it upheld the impeachment of Park Geun-hye, permanently removing her from office in a landmark ruling.

If the impeachment is upheld, a general election must follow within two months, setting the stage for further drama. While the case against Yoon appears compelling, the outcome is far from assured. The Constitutional Court holds the authority to decide Yoon’s fate, but even a single dissenting vote among the judges could nullify the motion. With Yoon having appointed three of the court’s members, the possibility of a reversal looms over the process, casting doubt on its impartiality.

In the aftermath of Yoon’s suspension, Prime Minister Han Duck-soo has assumed the role of acting president, steering a government mired in political chaos. The ruling People Power Party (PPP) teeters on the brink of collapse, with its leader, Han Dong-hoon, stepping down after a failed bid to unite the party against the impeachment vote. His resignation, citing the disintegration of the party’s Supreme Council, has left the PPP leaderless and vulnerable.

Meanwhile, the opposition Democratic Party senses an opportunity in the disorder. Armed with public outrage over Yoon’s actions, they are seizing the moment to press for an early general election. Such a move, they argue, would help restore South Korea’s dignity, renew public faith in its democracy, and offer the nation a chance at fresh leadership capable of undoing the damage to its global reputation.

The National Assembly’s members rose to meet a pivotal moment, understanding the weight of damage the nation was burdened with and the urgency of decisive action. On December 14th, they cast their votes in an impeachment process that South Koreans overwhelmingly supported, with over 70 percent of the public demanding Yoon’s removal. For the opposition Democratic Party, led by Lee Jae-myung, this political turmoil has paved a clear path to power. Yet Lee himself carries legal baggage, complicating his ascent.

For now, the opposition’s focus remains squarely on the presidency. The Democratic Party has vowed not to pursue impeachment proceedings against Prime Minister Han Duck-soo or other Cabinet members, citing the need to maintain a functioning government amid the political upheaval. Yet, analysts warn this restraint may be fleeting. Should Acting President Han fail to align with the Democratic Party’s agenda, Democratic leader Lee Jae-myung could reverse course, plunging the government into paralysis as political gridlock prevents key decisions from being made or implemented.

Yoon’s impeachment does not signify the end of South Korea’s political turbulence, nor the dawn of its resolution. Rather, it serves to close a shameful chapter in the nation’s democratic story. The true reckoning, however, will come with the election of a new president, one that promises further drama in a country already scarred by a crisis that has tarnished its reputation and weakened its hard-won soft power. For years, South Korea has worked to project its democratic ideals and cultural influence, but now it confronts the stark fragility of both. This moment of reckoning threatens not only its national identity but its standing on the global stage.