After consolidating power for decades, the Turkish president faces one of the most critical moments of his rule—not since the failed coup attempt, but in a new era where public opposition against him is stronger than ever. The tens of thousands who have taken to the streets in the past week are not merely supporters of Ekrem İmamoğlu, the imprisoned political rival of Erdoğan. Their outrage stems from a deeper concern: they see İmamoğlu’s arrest as a tipping point, accelerating Turkey’s shift from an authoritarian democracy to outright autocracy. Moreover, Erdoğan is seeking another term, despite it being constitutionally not allowed.

Autocrat Erdoğan?

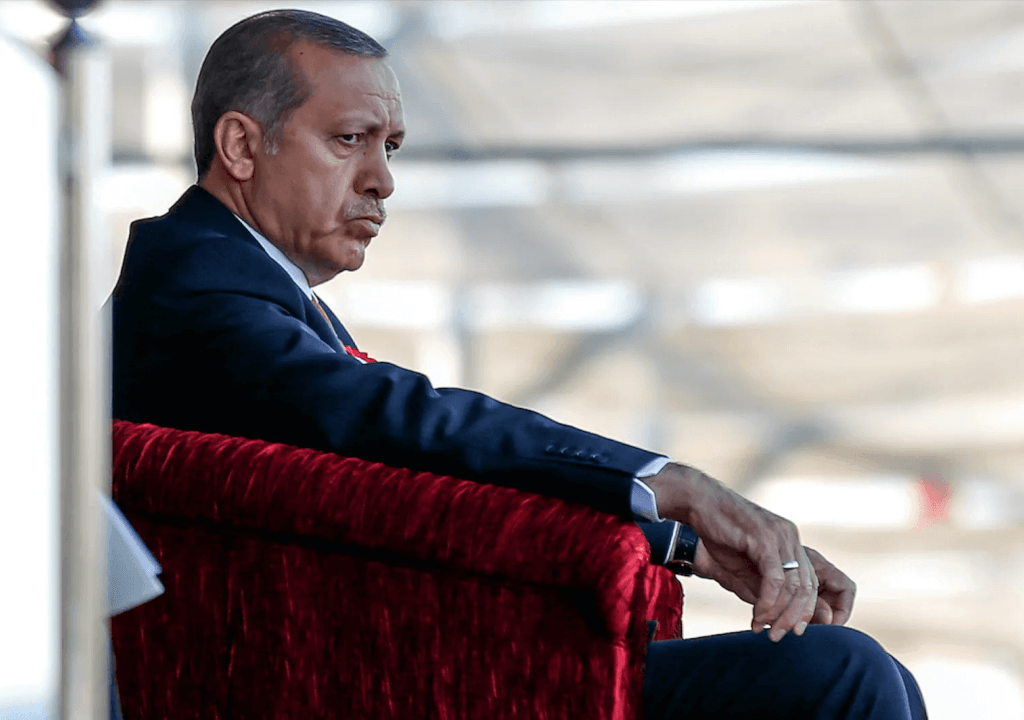

Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, a Turkish leader with deep Ottoman sympathies and a staunchly conservative ideology, has held power in various roles since 1998. He first gained prominence as the mayor of Istanbul—an influential political post—before serving as prime minister from 2003 to 2014. Since then, he has ruled as Turkey’s 12th and current president, systematically taking control of institutions, including the media.

With his Justice and Development Party (AKP) dominating Turkish politics for decades, Erdoğan has maintained an unyielding hold on power despite mounting economic and political crises. He has allowed no serious challenger to emerge.

At last, the opposition has found a formidable leader in Ekrem İmamoğlu, whose victory in Istanbul’s mayoral race directly challenged Erdoğan’s grip on the city. Now a central figure in the Republican People’s Party (CHP), the main opposition to the AKP, İmamoğlu has been propelled to the forefront of the 2028 presidential race after his party’s decisive win in the last local elections. Unsurprisingly, Erdoğan views him as a serious threat. And like any autocrat intolerant of dissent, he has acted to neutralize him—İmamoğlu has been arrested.

Escalating protests

But İmamoğlu’s recent arrest, widely seen as politically motivated, has sparked nationwide outrage, igniting protests across the country. In response, authorities have detained more than 1,400 demonstrators, including photojournalists and international correspondents, many of whom have been deported. The government has taken a hardline stance, tightening its grip on media coverage, while Erdoğan has dismissed the movement as “Evil.”

Yet, for many, the legitimacy of the charges against İmamoğlu is irrelevant. Their anger is not just about one man—it is a rebellion against a system they see as increasingly oppressive. What began as opposition to İmamoğlu’s arrest is rapidly transforming into a broader uprising, driven by years of political repression and an ever-deepening economic crisis.

Erdoğan wants it one more time

Resentment toward Erdoğan is mounting, but he shows no intention of stepping aside. Although the constitution bars him from running again in 2028 due to term limits, speculation is growing that he may attempt to circumvent these restrictions—either by amending the constitution or calling early elections. Many believe the opposition will be weakened long before then, as opposition figures, including İmamoğlu, have consistently faced political roadblocks both before and after elections, fueling concerns that Erdoğan will not permit a fair contest.

Yet securing another term will be no simple feat. Public frustration is intensifying amid soaring inflation, forcing the government to spend as much as $25 billion in a desperate bid to stabilize the lira—an economic crisis of its own making. Meanwhile, İmamoğlu’s affable and pragmatic image has broadened his appeal, even among conservative voters traditionally wary of the CHP. Erdoğan, however, appears to be banking on economic recovery and a fading sense of public outrage before the next election. At the same time, signs of political maneuvering are becoming increasingly apparent. A recent statement from jailed PKK founder Abdullah Öcalan, calling on fighters to lay down their arms, has fueled speculation that the government is seeking support from pro-Kurdish factions.

Although the next presidential election is still years away, İmamoğlu’s arrest on corruption and terror-related allegations suggests that Erdoğan sees him as a serious threat. Ultimately charged only with corruption, his detention came at a highly strategic moment—just days before the Republican People’s Party (CHP) was set to nominate him for the presidency. The controversy deepened further when Istanbul University annulled his diploma the night before his arrest, effectively barring him from the race. Both moves have been widely condemned as politically motivated. In response, an estimated 13 million people joined the 1.7 million CHP members in backing İmamoğlu’s candidacy, underscoring the resilience of opposition to Erdoğan’s tightening grip on power.

What happens next?

İmamoğlu’s arrest is, for many, a historical echo. Erdoğan himself once served as Istanbul’s mayor before being jailed—only to reemerge politically stronger. But that was in a far less consolidated political landscape. History has shown that Istanbul’s mayorship can be a stepping stone to Ankara, and İmamoğlu’s arrest has only invigorated the CHP.

Domestically, the party has shifted from street protests to alternative forms of resistance, including economic boycotts. Yet the demonstrations have forged an unusual alliance between formal opposition figures and politically disillusioned youth, each bringing their own strategies and grievances. This coalition remains fragile and could splinter under internal tensions. However, for now, their differences have fostered a dynamic movement—one that may prove more spontaneous, unpredictable, and ultimately formidable than Erdoğan anticipates.