The Swadeshi Movement was an important chapter in India’s independence struggle. It urged people to boycott British goods and support Indian-made products, sparking a wave of national pride and strengthening local industries. The movement also laid an early foundation for India’s push toward economic self-reliance. After independence, this cautious economic approach continued. Under the Indian National Congress–led governments, trade with Britain remained restricted.

While Britain had previously shown interest in building closer ties, India held back for years. But in 2014, India has undergone a major political shift, moving beyond decades of Congress Party rule. The new Hindu nationalist government came to power with a more critical view of Ottoman colonization than of British colonial rule. Since then, India has taken a more strategic and practical approach to global partnerships with Western nations. This shift became clear last week when India and the United Kingdom signed a long-awaited free trade agreement. The deal is expected to boost both economies and marks a fresh chapter in a relationship.

A ‘Historic’ Agreement

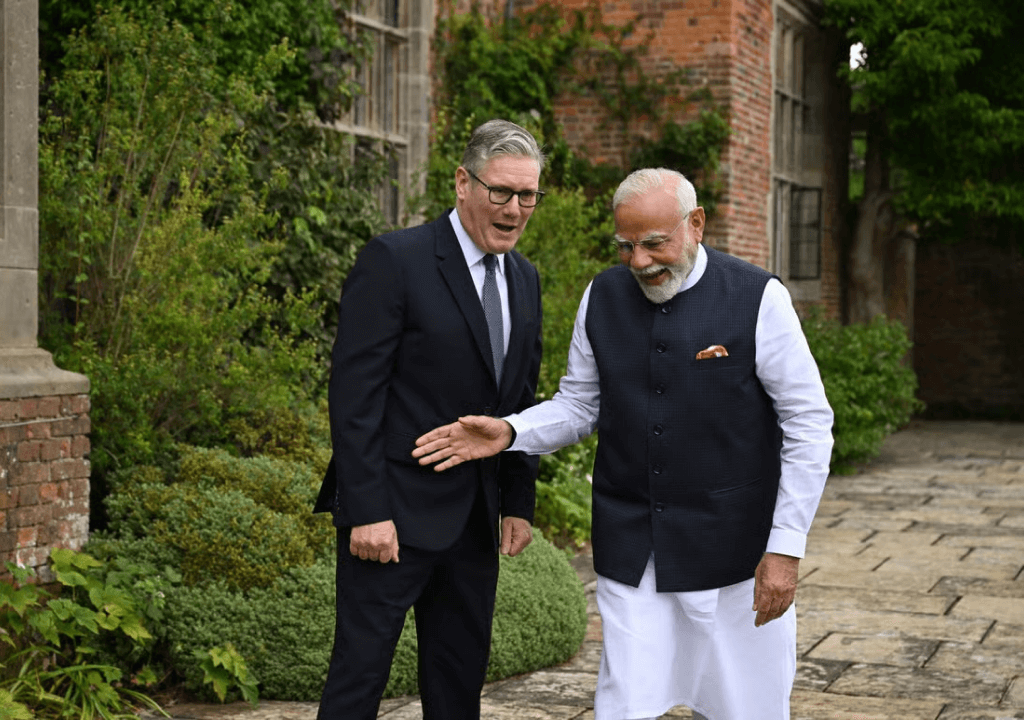

Keir Starmer and Narendra Modi hailed what they called a “Historic day” on Thursday, July 24, as the United Kingdom and India officially signed a long-awaited free trade agreement. The ceremonial announcement took place at Chequers, the British Prime Minister’s official country residence, where Modi, speaking through a translator, called India and the UK “Natural partners.”

For the UK, the agreement signals a much-needed economic lift and a post-Brexit show of global trade flexibility. The pact, projected to boost the UK economy by £4.8 billion annually and attract £6 billion in joint investment. For India, the deal sends a message that its £3 trillion economy, long shaped by protectionist policies, is becoming more open to international investment.

The negotiations, which lasted more than three years and spanned multiple governments, were finalized in May and brought to a close under Labour leadership, just ten months after Starmer’s government came to power. The speed of the outcome surprised even those closest to the talks.

Much of the credit goes to the strong working relationship between UK Trade Secretary Jonathan Reynolds and his Indian counterpart, Piyush Goyal. Officials on both sides stressed that trust was key to advancing the talks, often built through informal interactions.

Although the deal has been signed, it still requires approval from both the UK and Indian parliaments—a process expected to take several months.

What’s in the Deal?

The newly signed trade deal delivers major tariff reductions and opens up significant opportunities for both countries. Average tariffs on UK goods entering India will fall from 15 percent to just 3 percent. Scotch whisky duties, currently at 150 percent, will be halved immediately and gradually reduced to 30 percent over the next decade.

Indian exports will gain a major edge, with zero or reduced tariffs on 99 percent of goods shipped to the UK. This includes textiles, apparel, gems and jewelry, leather, machinery, auto parts, pharmaceuticals, agricultural products, chemicals, processed foods, and marine products. In the agricultural sector, 95 percent of UK tariff lines will now be duty-free. Key Indian exports like basmati rice, spices, tea, seafood, and packaged foods are expected to gain substantial momentum in the British market. The agreement clearly strengthens India’s position over regional export rivals like Bangladesh, Vietnam, and China. India will also welcome increased British investment in clean energy technologies such as solar, hydrogen, batteries, and electric vehicle infrastructure.

On the UK side, exporters will benefit from duty-free access for 64 percent of their goods sent to India, with further tariff reductions anticipated in the coming years. Sectors like digital services, cosmetics, processed foods, and alcoholic beverages will see expanded bilateral access. The agreement is also expected to boost cooperation in defense and emerging digital technologies. Prominent UK brands including Diageo, Jaguar, Land Rover, and Aston Martin will now enjoy expanded market access in India. The UK services sector stands to benefit from the arrival of 60,000 Indian professionals, helping to fill skill gaps in engineering, finance, and other high-demand fields.

Who Gains the Most in This Agreement?

Now that the deal is secured, the main debate is over who stands to benefit more. Public opinion in both countries remains divided. In the UK, segments of the population with roots in Pakistan and Punjab, some of whom support separatist movements in India, are likely to view the agreement through a skeptical lens. Traditional media outlets in Britain have also historically been critical of India, and this sentiment could shape how the deal is received.

Many British critics argue the agreement favors India disproportionately. Experts have pointed out that it offers limited gains for the UK, particularly in key sectors such as finance and legal services. Tom Wills, director of the Trade Justice Movement, criticized the pact for not including binding safeguards for labor rights, environmental standards, or public health. The London Mining Network raised similar concerns, pointing to the lack of strong climate protections, particularly in relation to coal mining practices in India.

Still, the deal provides British businesses with long-sought access to India’s rapidly growing upper middle class—a market that is among the largest and most dynamic in the world.

In India, the agreement has drawn criticism from certain left-leaning groups and nationalist factions who argue that it represents a concession to British interests. However, the government is expected to focus on the broader positives and promote the deal as a strategic success.

Overall, the agreement is being viewed by many as a win-win. It marks a significant step toward deeper cooperation.