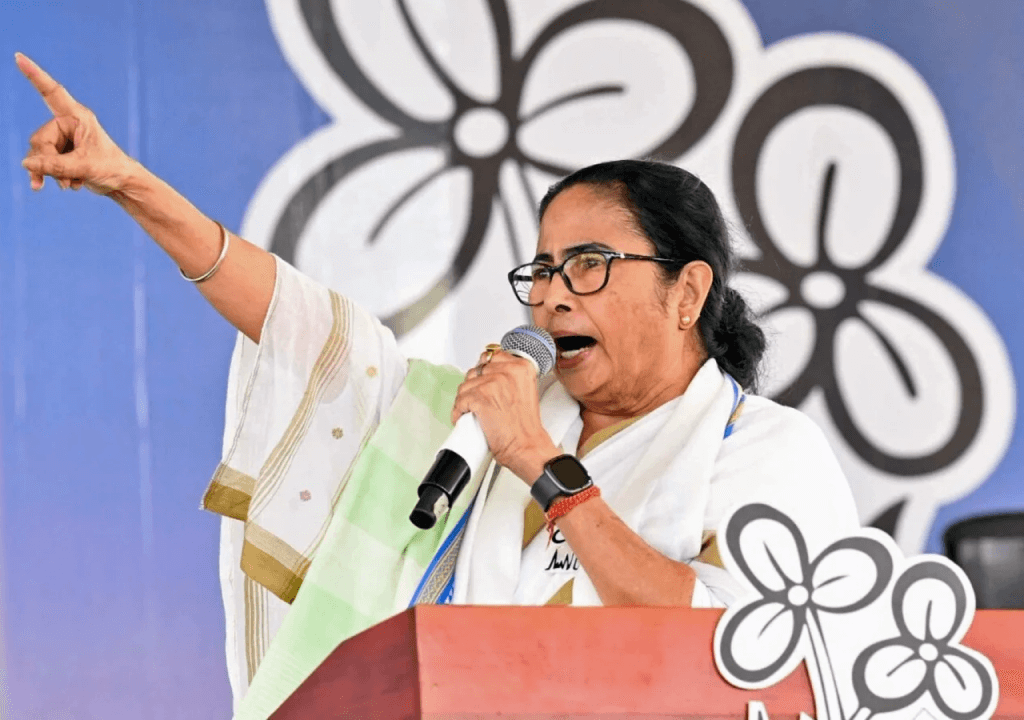

West Bengal, an eastern province in India, was once considered the think tank of the country, producing a row of talents that India was proud of, including Rabindranath Tagore, Asia’s first Nobel laureate in literature, and Oscar-winning director Satyajit Ray, among many others. However, now West Bengal is infamous for politically affiliated criminal gangs and their lethal conflicts. Almost every month, there are reports of violent political gang wars, with the government led by Mamata Banerjee, leader of the All India Trinamool Congress, frequently accused of supporting these criminal activities. Following last year’s notorious Panchayat (Local Body) elections, it was reported that almost 50 people lost their lives. Political violence in rural Bengal continues unabated. Local body leaders are being killed, party offices are being set on fire, and opposition party workers are being brutally attacked. Events like those in Sandeshkhali, where party leaders turn into powerful authorities and rule through criminal activities, preventing other parties from conducting political activities, are not isolated incidents. These issues persist as West Bengal faces another significant election for the Lok Sabha in Delhi.

Along with Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, West Bengal is one of the few states in India where polling is spread across all seven phases of the marathon election, largely due to security concerns arising from political feuds. The Election Commission chose to conduct elections by selecting a small number of constituencies in each phase to provide tight security for the election process and to allow security agencies to take complete control of violence-prone hotspots, thus avoiding deadly fights. Despite tight security by different state and central agencies, sporadic incidents of violence were reported across the state during the six completed phases. The Election Commission of India reported receiving nearly 1,000 complaints following the last phase alone, and police noted clashes and threats in various areas. Each phase has witnessed significant violence, whereas the rest of the nation, including volatile Kashmir, has hosted elections peacefully. Interestingly, despite the high political tensions, a higher voter turnout was recorded in Bengal, in contrast to the lower responses seen in the rest of India.

West Bengal is a crucial battleground in the Lok Sabha elections, contributing 42 seats to the 545-seat Lok Sabha (House of Commons), making it the third-largest contributor after Uttar Pradesh and Maharashtra. The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), aiming for a third consecutive term, needs to secure more seats from the state, having won only 18 out of 42 seats previously. The All India Trinamool Congress (AITC), the current ruling party in the state, is also strongly contesting the ongoing general election. The intense rivalry between these parties is leading to disastrous street fights and other criminal activities in the state. Formerly dominant parties like the Indian National Congress, and India’s biggest communist party, the Communist Party of India (Marxist), are also contesting the Lok Sabha election, but this time as allies, turning it into a three-way fight between the BJP, AITC, and the CPIM-Congress Alliance.

While the ruling All India Trinamool Congress (AITC) and BJP are now leading the violent politics, many experts believe that the past Communist years, which lasted for a long time, laid the groundwork for the current situation. The Communist Party of India (Marxist), or shortly CPIM, dominated the political sphere from the 1960s onward, displacing the Indian National Congress (INC) in the state. Like most communist governments worldwide, CPIM established groups capable of quashing political opposition in their strongholds. In some places, these groups evolved into more violent factions, including Naxals, who opposed the Indian Union. Even though CPIM distanced itself from Naxals, CPIM-supported groups, criminal gangs became increasingly common in West Bengal. The long rule of a single party, the bureaucratic culture of communism, economic decline of the state, and lack of employment all contributed to the evolution of political gang culture in Bengal. When CPIM was removed from power after a long tenure, many of these gangs migrated to the All India Trinamool Congress, where they continued their criminal activities. Interestingly, these gangs then started to target CPIM, their former supporters. However, with Narendra Modi’s seismic entry into national politics, the Bengal landscape was also shaken. The BJP replaced CPIM as the prime opposition party, possessing the finances, ideology, and power to challenge Trinamool Congress. And Bengal became the arena for these two heavyweights, further splitting the gangs into AITC-linked and BJP-linked factions. Many analysts fear that the BJP’s entry into Bengal may escalate political gang wars along communal lines, as the party represents Hindu nationalism, while Bengal’s large Muslim population, many of whom migrated from Bangladesh, stands firmly with the Trinamool Congress, paving the way for a potential communal clash in the future.

We cannot deem it democracy when violence becomes the means to seize power. However, in Bengal, violence is increasingly becoming a tool for political parties to assert control and uphold their dominance. Political parties shamelessly nurture individuals associated with violence. Police and judiciary intervention is limited due to extensive support for gangs from lawmakers. We cannot expect an end to this cycle as both state and central governments are complicit in using these criminals, regardless of their party affiliations. However, The decline of Bengal persists, with no concerted efforts to rectify the situation.