The Armenia-Azerbaijan war ended almost a year ago. Armenia lost the war, and Azerbaijan gained control of the Nagorno-Karabakh territory, a historic Armenian region also claimed by Azerbaijan. The Republic of Artsakh, the entity established by ethnic Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh, is officially dissolved, but tensions remain high. A peace treaty between the two countries is not yet possible, as this is not merely a political dispute over borders; it is an ethnic clash, and solving it is not easy.

Coexistence was only possible while they were under the Soviet Union; otherwise, ethnic clashes were common and led to deep-seated resentment. Peace can only be achieved through a formal treaty. Now, Europe and the West are taking a greater interest in resolving the issue, while conflicts of interest among the parties involved in the region persist. Russia supports Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan has strong ties with Turkey, Turkey has historical animosity towards Armenia, Armenia maintains a relationship with Iran, and Iran is an ally of Russia. This complex web of connections complicates the situation.

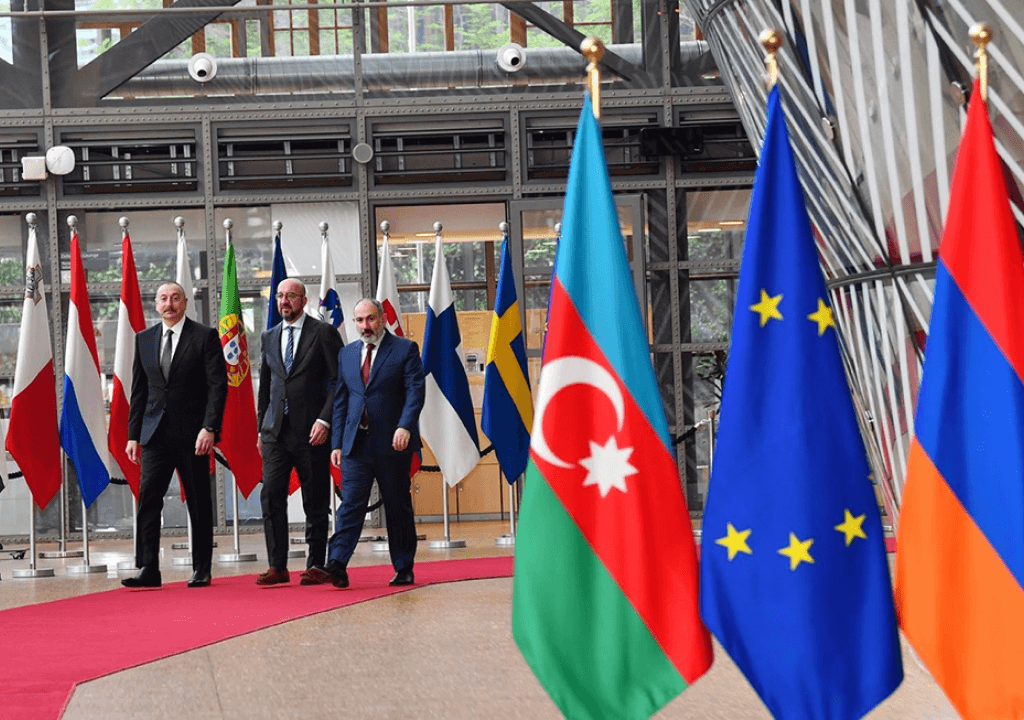

At the recent NATO summit in Washington, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken indicated that the Armenia-Azerbaijan peace process might be nearing a resolution. However, both Armenia and Azerbaijan are currently adopting a cautious stance, hesitant to show too much eagerness to make concessions. Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan and Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev were expected to hold direct talks in London during the European Political Community summit, but the meeting did not take place. As anticipated, both sides have accused each other of obstructing the discussion. Their most recent meeting occurred in Berlin in February, mediated by German Chancellor Olaf Scholz. This was the first encounter since Azerbaijan’s complete takeover of Nagorno-Karabakh in September 2023. At that time, the prospects for a peace agreement seemed remote.

In May, Pashinyan’s government made a significant breakthrough by agreeing to transfer four villages in disputed border areas to Azerbaijan. Since then, both sides have shown interest in finalizing a peace agreement. On July 20, Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev stated at a media forum in the Karabakh town of Shusha that up to 90 percent of the draft peace treaty has been settled. However, reaching an agreement on the remaining 10 percent may prove challenging. Azerbaijan’s demands including Karabakh pose challenges for Armenian politicians.

One major condition set by Aliyev is Armenia’s formal agreement to dissolve the OSCE Minsk Group, which has traditionally overseen the peace process but has recently been largely ineffective. Aliyev has criticized the Minsk Group for being biased towards Armenia and has claimed that it has been dysfunctional for many months, possibly even for a couple of years.

The second condition is more difficult: Azerbaijan is demanding that Armenia amend a provision in its constitution’s preamble that identifies Karabakh as part of Armenia. Aliyev has argued that this provision represents a territorial threat to Azerbaijan because it implies the unification of Nagorno-Karabakh with Armenia. This demand for a constitutional amendment could potentially derail the negotiations.

On July 25, an Armenian Foreign Ministry representative said that the government is preparing a response to Azerbaijan’s demands. Pashinyan has started internal discussions about possible constitutional amendments, leading to speculation that his government might be exploring ways to meet Aliyev’s conditions. Daniel Ioannisyan, a member of the working group on constitutional amendments, noted that any changes are unlikely to be finalized before 2027, and that modifying the preamble’s wording is not currently being considered. Edmon Marukyan, a former ally of Pashinyan and ex-ambassador-at-large of Armenia, said that Armenians are seeking clarity on several unresolved issues, including the process for returning prisoners of war.

While maintaining a tough stance on the constitutional provision, Aliyev’s administration extended an invitation to Armenia to attend the UN climate conference (COP29), which will be held in Baku in November. An administration representative described the invitation as a gesture of goodwill. Yerevan has not yet announced whether Armenian officials will attend COP29.

Countries situated in the small area between the seas and mountain ranges are struggling to resolve their tensions. The region is drawing the attention of various external parties, which could lead to increased volatility in the future. As a result, resolving ongoing disputes through a peace pact is crucial. Armenia, grappling with both domestic and international challenges, faces extra hurdles in reaching an agreement, with some emotional issues likely to persist across generations.