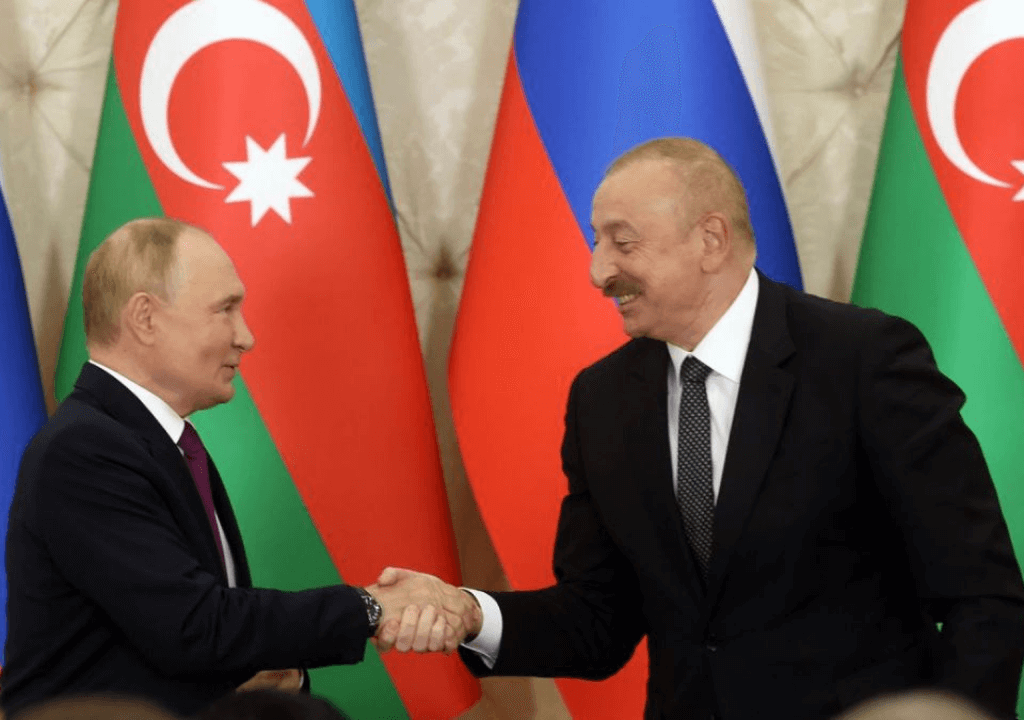

A superhero, a hyper-patriotic party, ineffective opposition, and an election controlled entirely by the ruling party. No, this isn’t about Russia – this time, it’s Azerbaijan. And the similarities are not superficial; they are very real. It appears that Azerbaijan, the oil-rich Caucasian country and a close ally of Russia, is replicating Putin’s tactics for maintaining power. Ilham Aliyev, Azerbaijan’s president and current ‘superhero,’ along with his New Azerbaijan Party, a nationalist conservative force and close friend of Putin’s party, secured victory in Azerbaijan’s snap parliamentary elections. These elections, opposed by the weakened opposition and criticized by election watchdogs, were widely labeled a sham.

Parliamentary elections were held in Azerbaijan on 1 September 2024, two months earlier than the originally scheduled date of November 2024. Since the Republic of Azerbaijan’s first parliamentary election in 1995-96, the New Azerbaijan Party has never lost an election and has consistently maintained power. And this time, the New Azerbaijan Party won a majority of 68 out of 125 seats. This outcome was expected, as there were limited alternatives for voters. The voter turnout, below 40%, reflects a lack of public interest in the election process. Campaigning was minimal and largely ceremonial, with the leading opposition, the Azerbaijan Popular Front Party, opting not to participate.

Although the election followed the model of Russia’s sham elections and its predictable outcome offered little hope for change, it still made headlines, particularly as it marked the first elections since Azerbaijan regained control of the Armenian separatist region of Nagorno-Karabakh following the war in September 2023. Constituencies in the reclaimed region also participated in the vote. Aliyev, credited with overseeing the annexation of Nagorno-Karabakh, and his party were expected to secure support. However, the opposition appeared to distrust the electoral process. Echoing Russia, reports of irregularities surfaced, further reinforcing the impression of imitation. The leading opposition party, the Azerbaijan Popular Front Party, boycotted the election for the seventh consecutive time. Musavat, the oldest existing political party in Azerbaijan, rejected the legitimacy of the new parliament, demanding another vote and accusing the election of widespread violations, including multiple voting, ballot stuffing, and undue pressure on observers. The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) also condemned the election, stating that it fell short of democratic standards well short of democratic standards. OSCE monitors reported that the campaign was barely visible and described the election as a contest devoid of competition.

The 125 members of Azerbaijan’s National Assembly are elected from single-member constituencies using the first-past-the-post system. Although the election results faced accusations of manipulation, the ruling New Azerbaijan Party of President Aliyev secured a narrow majority, winning 68 out of 125 seats. With the main opposition party boycotting the election, the second-largest bloc consisted of independents, who won in total 44 seats. The remaining seats were claimed by smaller parties. The official voter turnout was reported at 37.3%.

Influence from superpower neighbors is not uncommon, but it is striking how many former Soviet states have adopted similar administrative practices. Azerbaijan’s approach, in particular, exemplifies a model that closely mirrors Russia’s. This pattern often coincides with a troubling array of malpractices and mutual support among these nations. Such connections among these deceitful politicians are creating a power conglomerate that extends across borders and ultimately humiliates and mocks democracy.