The End of Eurasian Brotherhood? Azerbaijan Reconsiders Its Friends

Is Azerbaijan moving away from Russia’s influence? Explore the shifting dynamics, growing ties with Turkey, and what this means for the South Caucasus.

Is Azerbaijan moving away from Russia’s influence? Explore the shifting dynamics, growing ties with Turkey, and what this means for the South Caucasus.

A detailed exploration of the diplomatic strain between India and Turkey amid recent geopolitical developments.

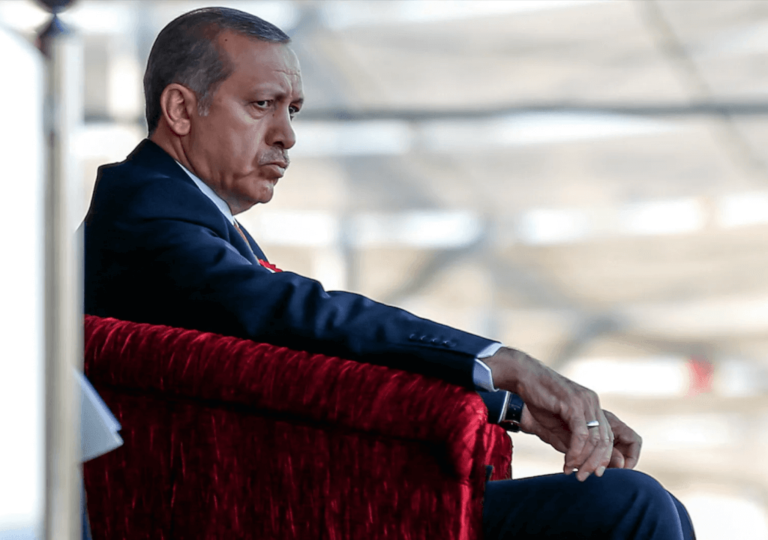

As protests erupt across Turkey, citizens push back against President Erdoğan’s growing authoritarianism. Is this a turning point for the nation’s political future?

The PKK has laid down its arms after decades of conflict with Turkey. What does this mean for the future of Kurdish-Turkish relations?

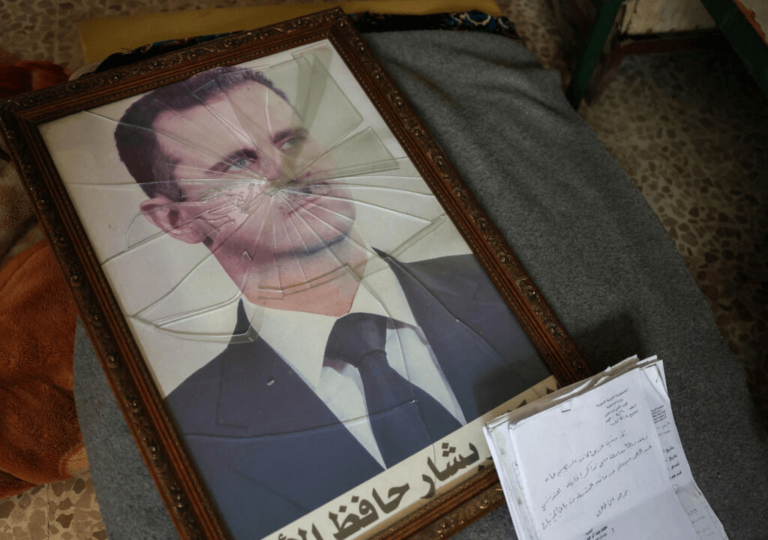

As Syria strengthens ties with Saudi Arabia, it signals a shift in regional power dynamics. Explore how this renewed alliance is reshaping the Middle East

Ahmed al-Sharaa has been appointed Syria's interim president, marking a significant shift after the Assad regime's collapse

Turkey's role in Syria has shifted, focusing on Kurdish relations and regional influence after Assad's regime fell

The Syrian civil war has officially ended, with Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham now governing a fractured nation

Turkey is reasserting its influence in Syria, targeting Kurdish forces amid a shifting power dynamic in the region

Rebels have seized Damascus, marking the end of Bashar al-Assad's regime after thirteen years of civil war