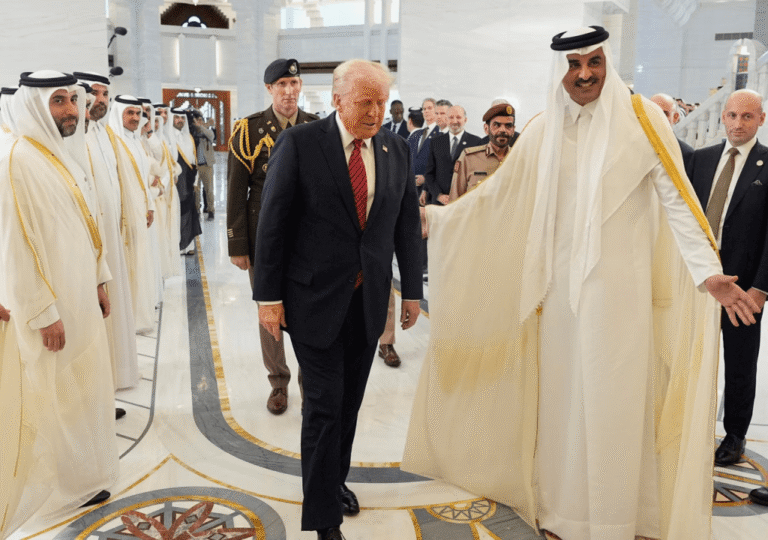

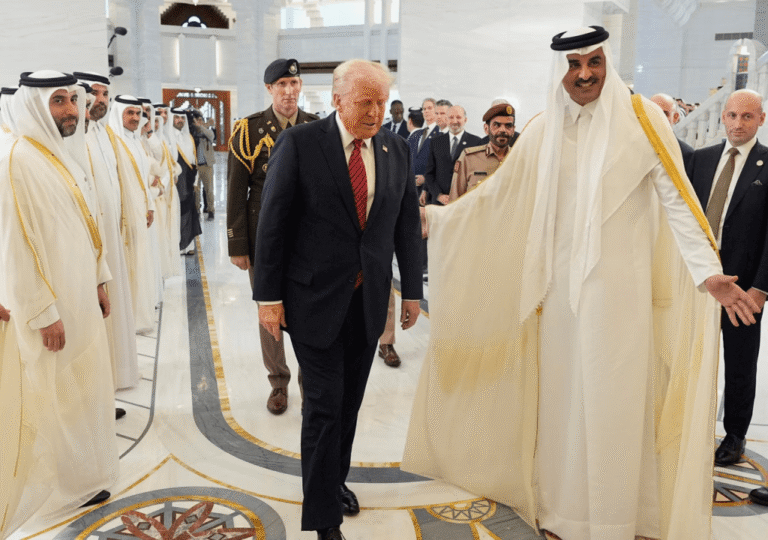

Trump and the Sheikhs: A Transactional Diplomacy in the Gulf

Donald Trump deepens U.S. relations with wealthy Gulf nations through high-profile arms and tech deals, positioning Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Qatar as key strategic partners.

Donald Trump deepens U.S. relations with wealthy Gulf nations through high-profile arms and tech deals, positioning Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Qatar as key strategic partners.

The UAE's strategic influence in Africa through diplomatic efforts, investments, and soft power initiatives

COP29 in Azerbaijan faced criticism for its focus on oil and lack of significant climate action

The 16th BRICS summit in Kazan highlights the bloc's growing geopolitical significance and its challenge to U.S. dominance

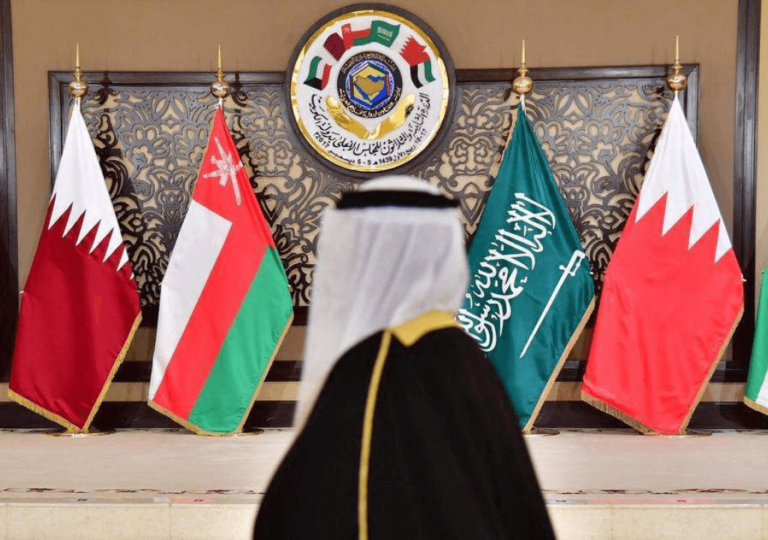

Amid trade wars, the EU's single market models economic cooperation, inspiring others like the Gulf Cooperation Council to form unified markets and compete globally.