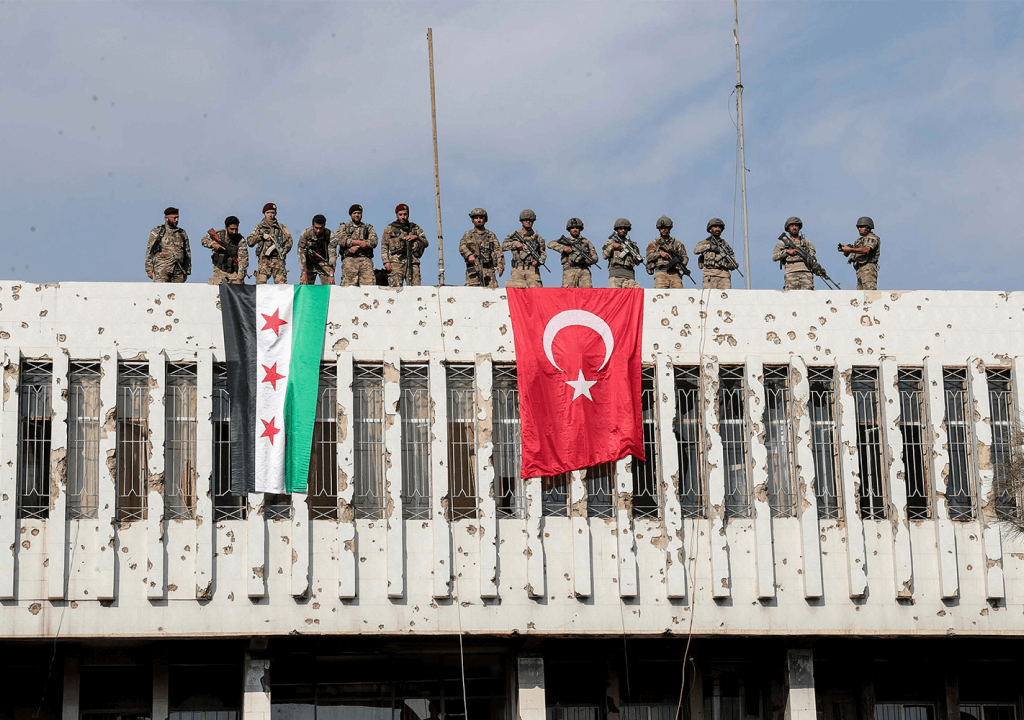

As Iran’s influence over northern Arab states wanes and Russia, once the region’s dominant power broker, finds itself severely diminished, Turkey—or Türkiye—has begun to reassert itself after a prolonged period of restraint. With its alliance solidified with Azerbaijan, Turkey has carved out a strategic foothold in Syria, where a coalition led by Ankara now commands key territories. In this reconfigured landscape, Turkey seems poised to wield the same influence in Syria that Iran once held under Assad. Yet Turkey’s ambitions in Syria go beyond expansionism. For Ankara, a stable, centralized Syrian government—free from Kurdish control—has become essential not only to securing regional dominance but to safeguarding its own national security.

Syria’s dominant rebel faction, which seized control of Damascus with Turkey’s blessing, has swiftly restored order to the city and appointed a new prime minister to head the country’s transitional government. Mohammad al-Bashir, the newly named premier, previously managed an administration in Idlib under the auspices of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), the most formidable of the rebel groups now occupying Damascus and other critical cities. It is evident that the new government will closely align with Turkish interests, with Ankara’s primary objective being the removal of Kurdish forces, who currently control a significant portion of northern Syria.

The Kurds, an ethnic group long settled in the rugged highlands straddling the borders of Turkey and the Arab states, have endured centuries of persecution and repression at the hands of various occupiers. Though most Kurds are Sunni Muslims, they have faced suspicion from both Sunni and Shia communities alike. The colonial division of the Middle East by the British and French in the early twentieth century left the Kurdish homeland fractured, divided among four states, with Turkey claiming the largest share. From the outset, relations between the Kurds and Turks have been fraught with animosity. What began as a simmering conflict soon escalated, with Turkey deploying brutal tactics to suppress the Kurds, while Kurdish militant groups retaliated with attacks on Turkish cities. Despite these tensions, Turkey ultimately maintained control over the Kurdish population within its borders, though the Kurds, united by a pan-Kurdish identity, sought refuge in Syria and Iraq. As the central governments in both countries weakened, the Kurds expanded their influence, breathing new life into the vision of a pan-Kurdish state—one that has, predictably, caused unease in Ankara. Following the outbreak of the Syrian civil war, Kurdish forces found new strength, securing territory with the support of international allies united in the battle against the Islamic State.

Turkey’s attacks on the Kurds have remained relentless, even as the Kurds fought alongside international forces against the Islamic State. However, the conflict in Syria took an unexpected turn after the Syrian civil war, with the ousting of Assad and the rise of Turkish-backed militants in Damascus. This shift led to an intensification of Turkey’s assault on Kurdish forces. In northern Syria, Turkish airstrikes have continued to target Kurdish positions, while the Turkish-backed Syrian National Army has clashed with the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), who receive U.S. support. According to the UK-based Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, at least 218 people were killed in just three days of fighting between these two forces in Manbij, northeast of Damascus.

A far more urgent concern is the potential downfall of the Kurdish militias, which could lead to the Islamic State’s resurgence. If these forces’ survival is threatened, the fate of the prisons—housing numerous ISIS fighters—will no longer be a priority. The collapse of these Kurdish-run prisons could trigger a dangerous wave of ISIS attacks, both within Syria and potentially beyond, creating a significant dilemma for the Trump administration.

Northeastern Syria is a region of remarkable ethnic diversity, home to significant Arab, Kurdish, and Assyrian populations, alongside smaller communities of Turkmen, Armenians, Circassians, and Yazidis. Contrary to common portrayals, it is not solely inhabited by Kurds. Supporters of the region’s administration argue that it functions as an officially secular polity with aspirations of direct democracy, grounded in the principles of democratic confederalism and libertarian socialism. These ideals promote decentralization, gender equality, environmental sustainability, social ecology, and pluralistic tolerance for religious, cultural, and political diversity—values reflected in its constitution, society, and political framework. The administration sees itself not as a separatist entity but as a model for a federalized Syria, advocating for decentralization rather than outright independence. Both partisan and non-partisan observers have praised the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES) as the most democratic system in Syria, citing its open elections, commitment to human rights, and defense of minority and religious freedoms within the region.

The government in Damascus, however, is a stark contrast. The Sunni Islamist militants, who have proven their governance in the small northern-western part of the country, have left minorities deeply suffering under their rule, prompting comparisons to the Taliban’s Afghanistan. Despite the assurances from HTS leaders that they aim to create a government that upholds the rights of minorities and women, such claims are met with skepticism. Should Turkey and HTS succeed in establishing a legitimate government with a fair constitution, the Kurds may be compelled to join and accept Turkish dominance. However, if governance mirrors that of Idlib, where minorities suffered under harsh rule, the Kurds will likely resist, continuing the fight.

On most occasions, Turkey—and the Turkish-backed government now exerting control in Syria—will likely resort to military force to annex Kurdish territories, particularly in the wake of Trump’s decision to withdraw U.S. forces, which has left the Kurdish military considerably weakened. Turkey perceives the Kurds as an ongoing threat to its strategic interests in Syria, and for Ankara, conflict appears to offer more leverage than peace. As a result, Turkey’s overarching goal to dominate Syria and dismantle the Kurdish region could spark more confrontations, further destabilizing an already fractured nation.