One of history’s most entrenched rivalries has reached a critical moment. Azerbaijan and Armenia have finalized a peace agreement after a conflict that ended in Armenia’s crushing defeat. The foreign ministries of both Caucasus neighbors have confirmed the treaty, marking what could be a historic breakthrough—though deep-seated animosities remain.

The hostility between these two ethnic groups stretches back centuries, shaped by a long history of massacres and territorial disputes that have left thousands dead. Their struggle over Nagorno-Karabakh, a region deeply intertwined with Armenian identity, has been a focal point of bloodshed for generations. Wars erupted with the Soviet Union’s collapse and again in 2020, before Azerbaijan launched a swift and overwhelming offensive in September 2023, reclaiming Nagorno-Karabakh and fundamentally reshaping the region’s geopolitics.

Today, relations between the two nations are at their lowest point. While international pressure—particularly from Europe and Russia—has long sought to push both sides toward reconciliation, negotiations have repeatedly collapsed under the weight of unresolved disputes.

Finally, a Peace Deal

Azerbaijan’s Foreign Minister, Jeyhun Bayramov, declared that negotiations on the peace agreement with Armenia had concluded, stating that Armenia had accepted Azerbaijan’s proposals on the two previously unresolved articles. Armenia’s foreign ministry later confirmed that the draft agreement had been finalized and was ready for signing. However, highlighting lingering tensions, Armenia criticized Azerbaijan for announcing the deal unilaterally instead of issuing a joint statement. Despite this, it expressed willingness to discuss the timing and location for the formal signing.

The peace deal ultimately took shape with Armenia conceding to Azerbaijan’s demands. Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan formally recognized Azerbaijan’s sovereignty over Nagorno-Karabakh, effectively ending three decades of Armenian separatist rule—a move widely viewed as a pivotal step toward normalization. Additionally, Armenia had already ceded four border villages to Azerbaijan the previous year, relinquishing territory held for decades. In the end, Azerbaijan secured an unquestionable victory, while Armenia endured a resounding and humiliating defeat.

Who Made the Deal Happen?

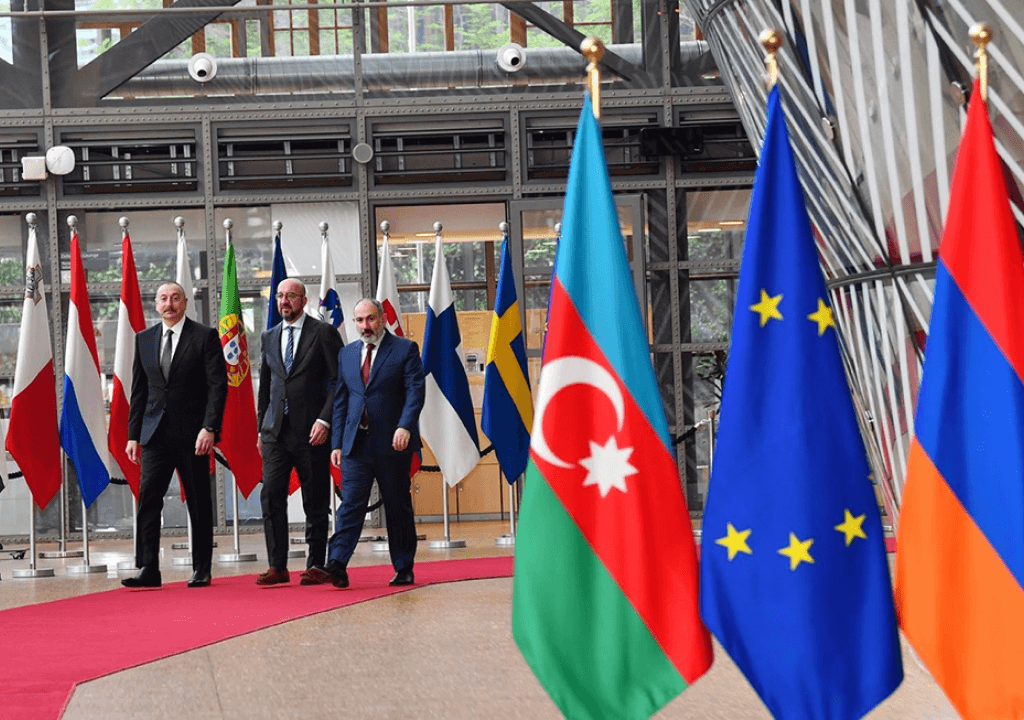

A peace deal had long been a priority for key regional players, particularly Russia and the European Union, both seeking to maintain their foothold in the region. Traditionally, Russia acted as the primary mediator between these deeply divided ethnic rivals, maintaining a peacekeeping presence. However, Armenia’s defeat in the war—and its sense of betrayal by Moscow—fundamentally shifted this dynamic.

Tensions over the conflict further strained Armenia-Russia relations, with Yerevan openly accusing Moscow of failing to provide support. In response to what it saw as Russian inaction, Armenia suspended its participation in the Russian-led Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) last year. While Russia, the United States, and the EU each attempted to mediate at different stages, Moscow’s waning influence became increasingly evident—not just in its inability to shape the outcome but also in the tone of official statements.

The Minsk Group—formed in 1992 under the leadership of the United States, Russia, and France—was originally tasked with overseeing the peace process. However, its relevance diminished over the years, particularly as Azerbaijan accused it of favoring Armenia. As a result, the draft peace treaty was largely negotiated outside the Minsk Group framework, with the final agreement reached directly between the two countries.

The credit for the peace deal goes to both Azerbaijan and Armenia. Despite the political fallout from Armenia’s defeat, Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan chose to push forward with negotiations, ensuring that discussions remained on track. With international actors facilitating the process, Azerbaijan reaffirmed its commitment to ongoing dialogue, expressing its readiness to engage in bilateral talks on normalization and other unresolved issues.

What Does It Mean for the Region?

Deep-seated ethnic animosities endure, passed down through generations, ensuring that distrust remains deeply ingrained. True reconciliation remains elusive, as neither side fully trusts the other, and the scars of war—along with the terms of the peace deal—are unlikely to fade from their collective memory. Azerbaijan, having secured a decisive victory, still harbors ambitions for further territorial gains at Armenia’s expense, a demand shaped by historical grievances and nationalist aspirations.

The region’s geopolitical complexities further heighten the uncertainty, deterring direct intervention from external powers. Russia has positioned itself firmly behind Azerbaijan while maintaining strategic ties with Turkey and, notably, Israel. Armenia, meanwhile, counts on support from Europe, the United States, and, unexpectedly, Iran—creating a tangle of alliances that makes the situation even more precarious.

With Azerbaijan holding the upper hand, the potential for renewed conflict remains high. Should Europe strengthen its backing for Armenia, Russia may encourage further Azerbaijani assertiveness, exacerbating tensions. At the same time, any instability involving Iran could ripple across the region, adding another layer of volatility. While the peace deal may provide a temporary reprieve, its long-term viability remains uncertain, leaving the specter of future conflict looming over the region.

More Issues to Be Settled

Disputes also continued over proposals for both nations to withdraw legal cases from international courts. Armenia and Azerbaijan remain embroiled in litigation before the International Court of Justice, the International Criminal Court, and the European Court of Human Rights, each accusing the other of rights violations committed before, during, and after their armed conflicts.

Pashinyan emphasized the need for clarity, stating that withdrawal from international courts must come with a complete renunciation of the cases. He warned that without such assurances, there could be a scenario where both sides formally drop their legal claims, only for Azerbaijan to later revive these issues bilaterally, potentially escalating tensions.

Azerbaijan has also made additional demands. Foreign Minister Jeyhun Bayramov stated that Baku expects Armenia to amend its constitution by removing references to its declaration of independence, which asserts territorial claims over Nagorno-Karabakh. Such amendments would require a national referendum. Meanwhile, nearly all of Nagorno-Karabakh’s ethnic Armenian population—more than 100,000 people—fled the region after Azerbaijan reclaimed it in a swift, 24-hour offensive.

In the months leading up to the announcement that the peace treaty text had been finalized, bilateral relations deteriorated sharply, raising doubts about a near-term settlement. Azerbaijan hardened its stance on securing a land corridor to Nakhchivan, while Baku’s rhetoric grew increasingly aggressive. This hardline approach now appears to have pressured Armenia—still reeling from its disastrous defeat in the Second Karabakh War and Azerbaijan’s reconquest of the region in late 2023—into making key concessions on the treaty’s most contentious issues.

With their differences on two critical negotiating points now settled, Armenia and Azerbaijan seem to be advancing toward the formal signing of a peace agreement. However, this does not guarantee lasting peace for both of them.